Hong Kong government confirms Chinese text of national security law prevails over English

- The move has been criticised because of differences between the two versions of the law

- There is still no official English translation

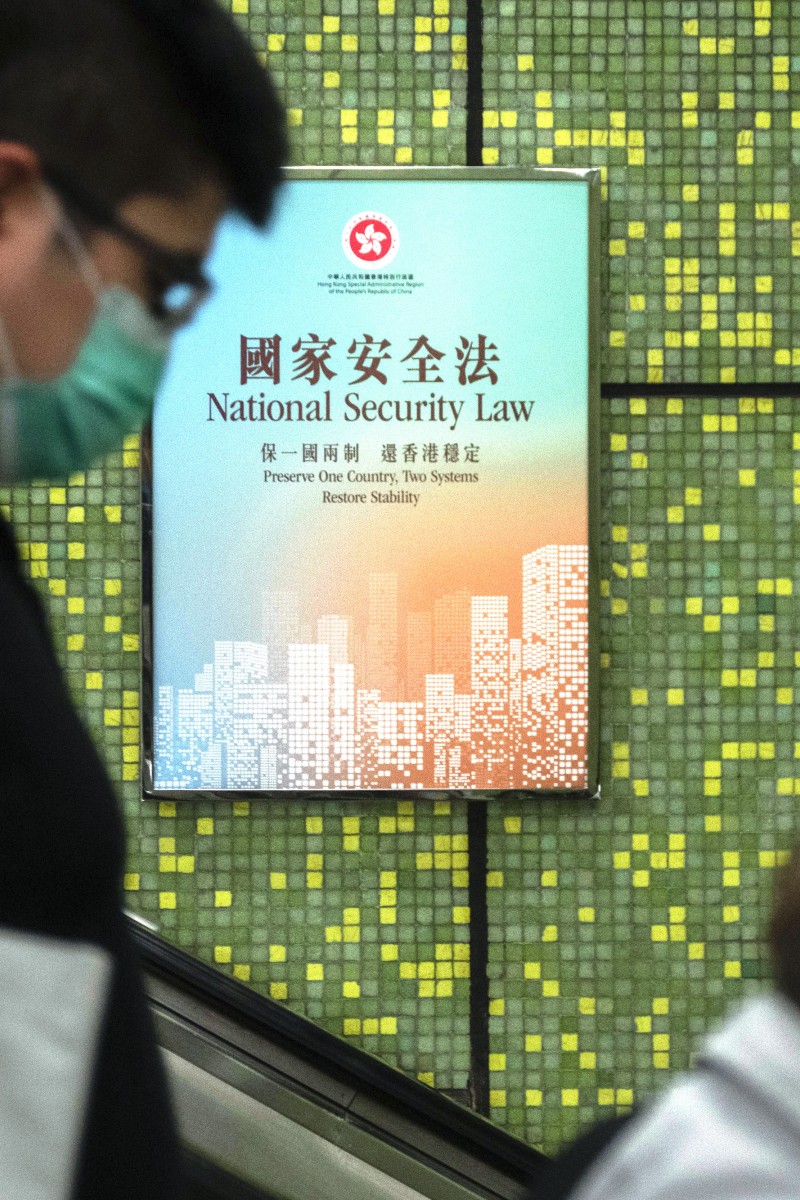

Pedestrians ride an escalator near a Government National Security Law poster in Wan Chai MTR station. Photo: Bloomberg

Pedestrians ride an escalator near a Government National Security Law poster in Wan Chai MTR station. Photo: BloombergThe Chinese version of the new national security law will prevail over the English translation in the event of any discrepancy between the two, confirmed the Hong Kong government, in a marked departure from the city’s official language policy which gives equal weight to both languages.

But the move was sharply criticised by one lawyer, who noted discrepancies between the two versions, adding he had never seen such a poorly drafted piece of legislation. A retired judge admitted he was having difficulty understanding the English version.

The government gazetted the law in Chinese at 11pm on Tuesday after it was passed by China’s top legislative body, the National People’s Congress Standing Committee.

Books by pro-democracy advocates being reviewed under national security law

Hours later, Xinhua state news agency released a translation, but one it described only as “a reference” and it does not have official status in the city. The official English version was published on the government’s website only on Friday, three days after the law came into effect.

The law aims to stop and punish acts of secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces, with offenders facing up to life imprisonment.

According to the Official Languages Ordinance, Chinese and English possess equal status and enjoy equality of use for communicating between the government and the public.

In a reply to the SCMP's enquiries on Sunday, the Department of Justice confirmed Chinese was the official language of the new law because it was a national law enacted by the standing committee. “During the enforcement of the law by various government bureaus and departments, if necessary, they could seek legal advice from the Department of Justice,” a spokesman said.

But practising solicitor Alan Wong Hok-ming questioned whether the government had a legal basis to determine the Chinese version would prevail.

“This is unacceptable,” Wong said. “The government needs to tell us which piece of legislation supports its statement about Chinese as the official language of this new law. You can’t just decide it on your own. The government should have the letter of the law to support its statement.”

Yet the law made no mention the Chinese-language version would predominate, he noted.

“But as there isn’t such a provision in the law it means that the government’s statement doesn’t have any legal effect,” he said.

Hong Kong netizens invent new protest slogans

Wong pointed to differences between the two texts. For example, Article 9 and 10 of the English version regarding supervision of matters related to national security carry the word “universities”, while the Chinese one just refers to “schools”.

“Whether universities should be subjected to the government’s supervision will be a big dispute,” he said.

The legislation was generally badly formulated and lacked clear definitions of key offences, said Wong. “This letter of this law shows that it is badly written with the drafters taking a flippant attitude,” he said. “I have never seen such a law so poorly written. For example, there’s a lack of definition of many terms such as ‘national security’.”

Problems would crop up if Chinese was the official version of the law, he predicted. “How will foreign judges or lawyers understand this law? This is the problem the authorities need to address,” he said.

Blank Post-it notes have replaced protest-related material on a restaurant's Lennon Wall, after the national security law imposed in Hong Kong by China. Photo: SCMP/ Xiaomei Chen

But Basic Law Committee member Priscilla Leung Mei-fun defended the government’s decision.

“It is a national law. And there is actually not an official English version. So we should refer to the Chinese text if there is discrepancy,” Leung said. “Sometimes, on the mainland, there are authorised English translations of court verdicts after a case is decided, so foreigners can also understand the law and the verdicts. But for the judge, he or she will only base a ruling on the Chinese text of a law.”

Anita Yip, vice-chairwoman of the Bar Association, noted the gazette notice of the English translation stated it was “published for information” only.

“The newly gazetted English version does not purport to be an official version,” she said.

Secondary school to investigate teacher protest-related misconduct

Yip called on the government to enact an authentic English version as foreign judges and lawyers who did not read Chinese would have difficulty in understanding the law.

“It is hoped that the ... government will publish an authentic English version forthwith,” she said. “Many residents and foreign investors don’t read Chinese. These discrepancies only reinforce the need for an authentic English version.”

Former Court of Final Appeal judge Henry Litton told the SCMP he had problems understanding the English translation of the law. “I do have some problems with the language in Xinhua’s version. I am, at present, struggling (with the help of a friend) with the Chinese text,” Litton said.