What is it like living with anorexia? A recovering sufferer explains, and gives advice for those with eating disorders, and their loved ones

Two years into recovery from her eating disorder, Chinese International School student Steph Ng shares her experience of battling the illness and how it affected those around her

People who have never experienced eating disorders often have many misconceptions about them, and about what life is like for the people who have them. Outsiders often associate eating disorders with particular behaviour or appearances, to the point where "eating disorders" is simplified to "vomiting, not eating and being too thin". Eating disorders become the punchline of jokes, and those with disorders are sometimes judged harshly by people who have no idea what an unforgiving illness it can be.

Eating disorders are rarely mentioned in Hong Kong, so many people think we don't have these problems. But ignoring the problem only makes things worse.

Of the 85 per cent of women in Hong Kong who want to lose weight, only 0.06 per cent are actually overweight, according to an article published in The Hong Kong Practitioner by Chinese University psychiatry Professor Kelly Y. C. Lai . Women often don't even know that they have an eating disorder, despite having severe health complications. Even if they do realise that they have a disorder, it is almost impossible to find a specialist who has studied or has in-depth knowledge of eating disorders.

We have no idea what we are talking about when it comes to this touchy topic, and it is time to change that.

The eating disorder pit

What it's like for outsiders:

To outsiders, eating disorder sufferers are control freaks. It's as if they follow irrationally strict rules, have multi-personality disorder, and aren't able to compromise. To anyone who has never experienced this illness, the mindset is virtually impossible to understand, and seems annoying and attention-seeking.

What it's like for the family:

Watching a loved one struggle and not knowing how to help is tough. The sufferers are often unable to keep track of how their own minds are changing, let alone explain the situation to their families. Confused and helpless, families sometimes become angry and frustrated with the sufferer.

What it's like for friends:

Friends normally see the sufferer for only limited periods of time, such as at school, so they are often unaware of things until the sufferer tells them, or at a later stage if they notice obvious physical and behavioural traits. Unable to see beyond their limited contact, friends often choose to distance themselves.

What it's like for the sufferer:

Food is not the sufferer's enemy. It becomes the only thing the sufferer thinks about: it is the only thing that is measurable, reliable, and controllable when everything else in life seems so out of control. "It's much more about controlling life or other difficult issues than about weight," agrees Dr Cathy Tsang-Feign, a psychologist and expert in treating eating disorders. "Having a name for something that gives [them] control gives [eating disorder victims] a sense of pride."

By associating thinness with success, losing weight becomes synonymous with success. Food becomes the object of control: eating "too much" reminds them of the lack of control in their life, and eating less gives them a sense of taking charge.

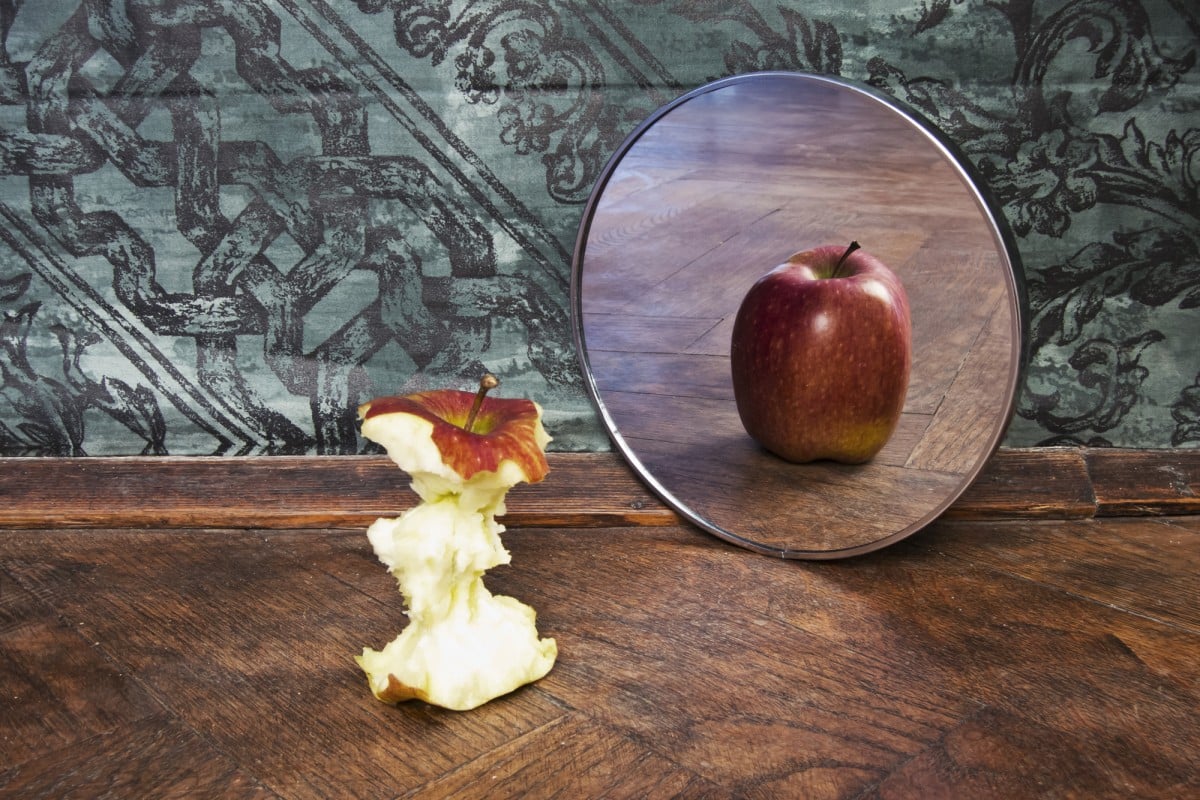

My goal to be "thin" depended on emotions rather than concrete results. I was happy when the scale told me I had lost weight, but if I looked in the mirror and I felt fat, I would immediately strive to lose even more. The scary thing about the mind is that it plays games.

By the time I reached a goal, it had already changed, and so I was never satisfied with my progress.

Climbing out

What outsiders think it's like:

There should be a click, one life-changing moment where the sufferer suddenly realises their worries are needless, and they need to change their ways immediately.

What the family thinks it's like:

Watching someone you love go through mental struggles is incredibly taxing. Family members are under constant pressure to detect harmful behaviour, and it is extremely stressful to think that one wrong action or statement can break the sufferer. "There is so much tension when the illness hits. The parents become so stressed about their child, and the child becomes so stressed about their parents' constant misunderstandings," says Tsang-Feign.

Communication is especially important during this stage. It is important for family members to use each other to vent feelings of frustration, to keep each other updated, and to discuss recovery strategies. Through a family Whatsapp group that we shared, my family and I were able to keep one another updated on my situation - victories and failures included - and plan for the future accordingly.

What it's like for the sufferer:

The change was gradual and was done subconsciously - in fact, if you asked me to pinpoint moments where I started getting better, I wouldn't be able to. My recovery was a culmination of small changes made in my lifestyle that slowly turned into habits I could sustain.

Helping a loved one with a disorder

Be the example you want to see

During recovery, sufferers are relearning how to eat and behave healthily, and they look to those around them to be models of this behaviour. The sufferers need to get over associating food with fear. They must learn to be open-minded to every type of food first, before they can learn to independently make food choices that are right for their lifestyle.

Be supportive and trustworthy

Often, desperate family members resort to tricking the sufferer to minimise the physical impacts of the illness. For example, they may cook food in butter and cream so the sufferer gain weight. Although this may work out in the short term, it will backfire in both mental and physical aspects of the sufferer's life.

Firstly, once the victim realises that he or she is gaining weight, they will immediately take dramatic measures to lose weight again, which will not only cause extreme anxiety and depression, but also cause a large amount of harm to an already failing body. Secondly, the sense of betrayal and loss of trust will end up as yet another obstacle on the road to recovery.

It is tempting and understandable for loved ones to try to sneak the victim into recovery, but one thing that you must remember is this is a mental rather than physical illness. Recovery involves more than physical rehabilitation; it requires patients to acknowledge their problem, trust you to guide their way, and work with you to achieve their goals.

Don't be aggressive

You are allowed to be angry, but know that "tough love" doesn't work. Shouting, criticising or even saying empty things like "You're beautiful just the way you are" does nothing but further widen the gulf that forms between the sufferer and their families. Instead, families should always aim to discuss the issue with the sufferer to understand their point of view. "Just showing that you care is enough," reminds Tsang-Feign.

Out of the pit

What it's like for outsiders:

They often never suspect a thing. That is the most beautiful thing about recovery: when you step back into the real world, you are "normal" once again.

What it's like for family members:

Loved ones often need to re-learn "normal" behaviour as much as the sufferers do. After dealing with deceptive behaviour for such a long time, they may be mistrustful even after the sufferer has recovered. For example, if the sufferer declines food because they feel full, family members may instinctively want to force them to finish it anyway.

However, family members must understand that to help those in recovery re-adopt regular social habits, they need to be treated as recovered, and not sick. Of course, this is provided the sufferer has already shown they can lead a balanced lifestyle and are in no danger of relapsing. Loved ones should always step in when noticeably self-harming traits begin resurfacing during recovery, but they should let go when the sufferer demonstrates the capability to be independent.

What it's like for friends:

Most friends often find the topic of eating disorders too touchy to talk about. They shy away from mentioning the subject around someone in recovery, and begin to mumble whenever it comes up in conversations. If a person in recovery doesn't want to discuss it, friends should respect that. However, if they openly decide to bring it up in conversation, friends should address it. Discussion brings about deeper understanding, and words of encouragement do motivate.

What it's like for the sufferer:

Recovery is letting yourself start life over again and letting go of the damaging habits you once held. The detachment from who you once were can be jarring. When I re-read the diary, I kept during my illness, it sounds like a completely different person.

But my eating disorder is a part of me, and it always will be. Eating disorder sufferers want to run away from their past as soon as they begin recovering, but those who have lived this illness should remember their past. Learn to accept that it happened, and that there will still be bad days.

The ABCs for warriors still in battle:

ADMIT you have a problem:

The reason eating disorders can be so difficult to overcome or even identify is that all of it happens in the mind of the affected. The illness is what the sufferer makes it, and if they are unwilling to seek help, admit that the illness is damaging their life, or even admit that they have this illness, then it's a dead end.

BE open-minded with healing options:

The people who help you most don't necessarily have to be psychologists, and the methods that you use don't have to be "right" for anyone but yourself. My biggest saviours were my family and my nutritionist. In fact, the first two psychologists I saw did nothing for me but reinforce the ignorance this illness continues to face every day and/or attempt to educate me on the generic causes and consequences of this illness - things that were not helpful to me at the time.

COMBAT your illness in ways that work for you:

When I was recovering, I used methods that might be deemed "inappropriate" for eating disorder victims. For example, to convince myself to swallow the full-fat milk that my nutritionist prescribed to me for breakfast, I would research "full-fat milk for weight loss" on the internet as encouragement. This strange method may be frowned upon, but one way or another, I downed the milk.

My point here is, if you can find a way to convince yourself to move in the direction that the people who are caring for you have pointed out, do it. Ultimately, your mind is your own, and only you will be able to steer it the way you wish.