Art with a repurpose: artists behind Plastic Wood Studio discuss what they’re doing about Hong Kong’s waste problem

- The studio recycles plastic bottle caps, makes art, and leads environmental workshops at schools, but its founders explain why individual action is still not enough

- Every week, Talking Points gives you a worksheet to practise your reading comprehension with questions and exercises about the story we’ve written

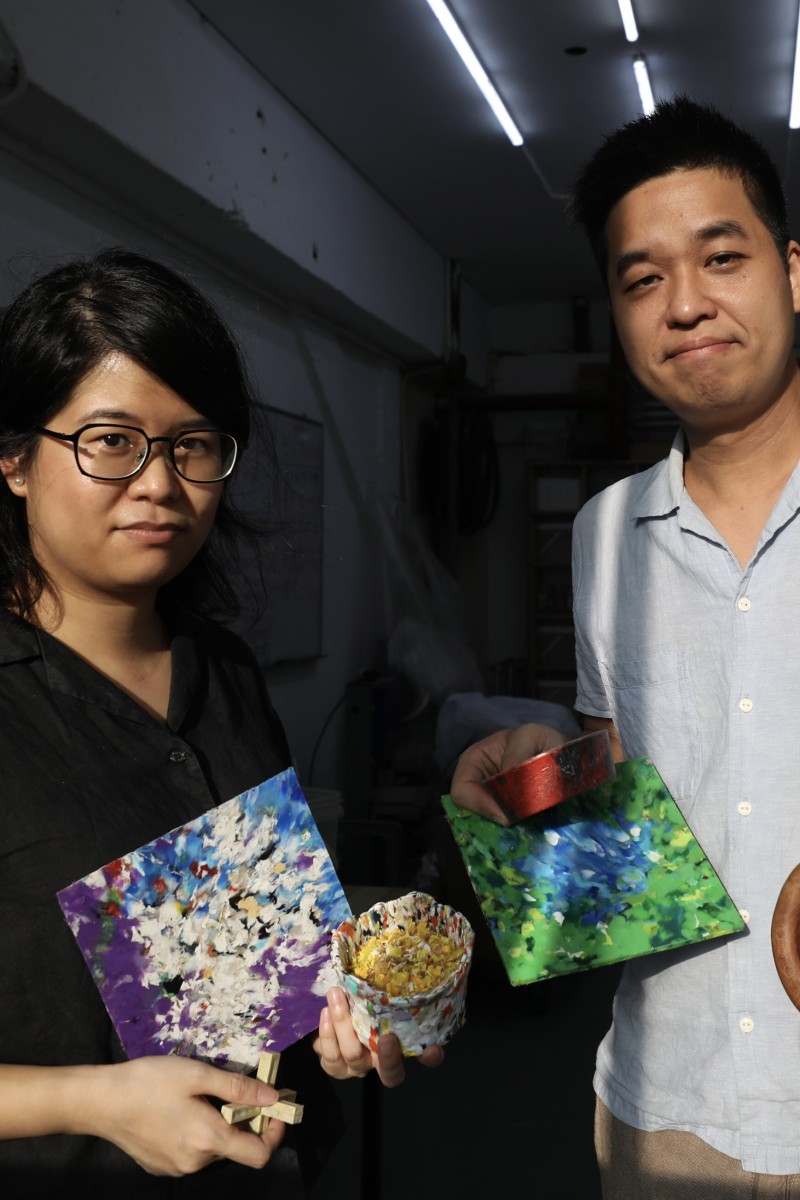

Laura Li Nogueira (left) and Boy Yiu Kwan-ho have found many different ways to repurpose the plastic that cannot be recycled in Hong Kong. Photo: Xiaomei Chen

Laura Li Nogueira (left) and Boy Yiu Kwan-ho have found many different ways to repurpose the plastic that cannot be recycled in Hong Kong. Photo: Xiaomei ChenIn the hands of Hong Kong artists Laura Li Nogueira and Boy Yiu Kwan-ho, even plastic rubbish can become art, flower pots, clocks and even phone stands.

A visit to Thailand three years ago opened their eyes to the danger that plastic rubbish poses for the environment. Since then, the two visual art graduates have been on a mission to save the Earth through what they do best – art.

In 2018, they visited Thailand on a cultural exchange programme. There, they were shocked to see heaps of plastic bottles floating in rivers, or piled up near where locals lived.

“We were shocked to see plastic waste so close up. In Hong Kong, we don’t usually see where our waste goes,” said Yiu, who is 37 years old.

During the exchange programme, the pair spent three weeks using plastic bottles to build a house about nine square metres large. This was their attempt to raise awareness of the rubbish being dumped into the rivers.

After returning to Hong Kong, they founded Plastic Wood Studio in March 2019 as a workspace for plastic recycling and manufacturing. They were following the model of Precious Plastic, a plastic recycling project based in the Netherlands.

The studio would collect plastic bottles and bring them to Green@Community, a government-run recycling facility. They would trade plastic bottles in exchange for bottle caps, which cannot be recycled in Hong Kong.

Currently, only a plastic bottle’s body can be recycled at the city’s waste facilities. Other parts – such as the caps, rings and film packaging – are sent to landfills. For this reason, the studio uses the non-recyclable bottle caps to create something new.

Founder of Instagram thrift store on reducing Hong Kong’s waste in fashion

According to the Environmental Protection Department, plastic waste made up the third largest category of municipal solid waste in landfills in 2019. That year, about 846,800 tonnes of plastic waste were disposed of in Hong Kong. Yet only 74,400 tonnes were recycled.

Yiu and Nogueira said most art in the city was typically thrown out after an exhibition. So, they explored ways to be creative while limiting the waste they produced.

But the process of giving plastic waste a new life is not easy. After cleaning the pieces, the studio separates the plastic by colour and shreds them. Then, they use a machine to compress and melt the shredded plastic pieces into boards of different thicknesses.

“The compression process is long. It can take an hour just to make two to three boards,” Yiu said, adding that the melting plastic also would produce an odour.

The Hong Kong student educating her peers on plastic pollution

In addition to reducing their own waste, the studio collaborates with schools to host educational workshops, empowering student participants to redesign the schools’ recycling systems.

The programmes last half a year or a full year at each school because that is usually the amount of time needed for students to develop habits that are more environmentally friendly.

During the programme, the instructors explain what can be recycled in Hong Kong and teach about the city’s current waste situation. They also bring the studio’s plastic processing machine to show students how it is used.

After a month of walking participants through the recycling process, the instructors let them run the machine on their own for a couple months, while providing help when needed. By the end of the programme, students are usually able to create their own products made from recycled plastic. Some even sell their work at school fairs.

Although the studio has certainly made an impact over the past two years, Nogueira and Yiu agree that individual actions can only go so far. Yiu said existing environmental policies were inconvenient for most people.

He used the Drink Without Waste initiative as an example. The government-funded scheme has now ended, but it used to pay citizens 5 cents for every bottle or carton they recycled. Yiu commended the government’s intentions, but added that these facilities were not enough.

Nogueira, who lives in Central, agreed, saying there were no recycling facilities near her neighbourhood. A 5-cent enticement was not enough to encourage people to walk a few blocks just to recycle a bottle.

“My parents would just throw them in a rubbish bin on the street instead,” said 35-year-old Nogueira.

‘Drink Without Waste’ collects more than 1,000 tonnes of plastic bottles

This is what they foresee happening when the city’s new waste-charging plan is implemented. The legislature recently passed the scheme, and the government will spend at least 18 months preparing for the new waste-collection programme.

“It’s always a lot of talk, but little gets done when the government proposes environmental policies,” Yiu said.

To more effectively reduce plastic waste, the government should design a mandatory producer responsibility scheme (PRS), he said. This means that the company that produces something must also take up the responsibility to collect and recycle the waste generated.

This method could keep businesses from generating so much plastic in the first place.

Everything you need to know about the city’s new waste-charging scheme

Leanne Tam Wing-lam, campaigner for environmental protection group Greenpeace, agreed with the idea that recycling was not the solution to the city’s waste problem.

“Recycling is a down-cycle. Not everything can be recycled,” Tam said, adding that the process was also costly. A down-cycle is when waste is recycled, but the new product is lower in quality and less valuable.

She also said distrust of the government was another reason Hong Kong was slow in fixing its waste problem.

Face off: Should Hong Kong residents be charged for their rubbish?

Recently, staff from Green@Community were found dumping recyclables into rubbish bins. This has raised questions about how much of the facility’s waste actually gets recycled.

Tam is also confused about the government’s reluctance to set a clear date or goal for reducing waste, and compared it to Canada’s plan to achieve zero plastic waste by 2030.

“The government should bear the responsibility of leading businesses and citizens when it comes to protecting our environment,” Tam said.

Click here to download a printable worksheet with questions and exercises about this story. Answers are on the second page of the document.