The fight to keep Hong Kong heritage and Hakka kung fu alive for future generations

- Three Hakka kung fu masters talk about martial arts and their attempts to preserve the stances and strikes before it’s too late

- Hakka kung fu was originally created for very practical reasons – to defend a tribe against outsiders

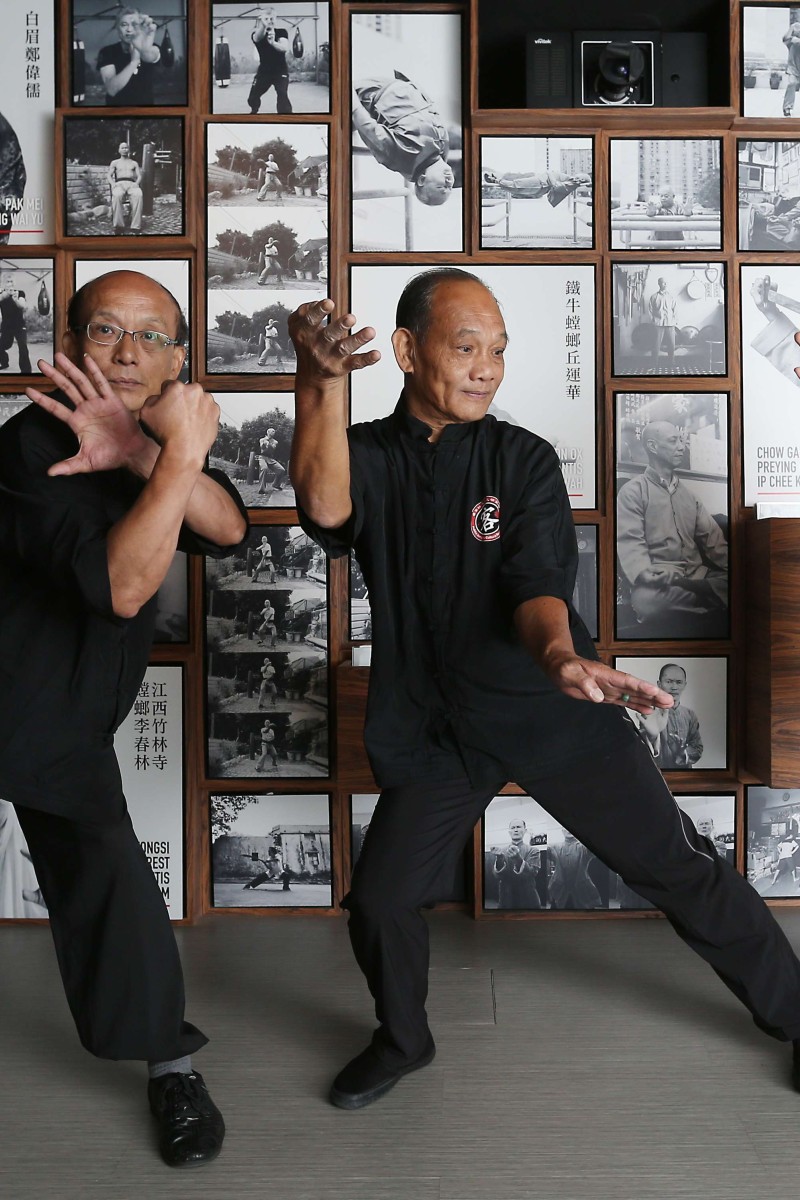

Kung fu masters (from left) Wong Tung-ming, Fu Tin-son and Lai Chung-Ming contributed towards the martial arts exhibition at City University.

Kung fu masters (from left) Wong Tung-ming, Fu Tin-son and Lai Chung-Ming contributed towards the martial arts exhibition at City University.When Wong Tung-ming boxes, you can literally feel the strong wind that’s generated by his fists. He’s a master of Tung Kong Hung Kuen, one of many Hakka kung fu factions.

Hakka kung fu was originally created for very practical reasons – to defend a tribe against outsiders. Everyday items in Hakka life, like shoulder poles and jars, could be used as weapons, and there are moves that are more useful when performed in close quarters. This is because Hakka tribes used to live in villages.

“The horse stances we use are narrower [than in other forms of kung fu] because space was limited in villages and we had to make our moves more aggressive,”says Lai Chung-ming, a master of the Pakmei faction. “We didn’t have anywhere to move, so we had to generate a lot of force for hits. If you stopped paying attention for a second, you ran the risk of being pushed off a cliff or into a river.”

The Hakka people have, since the Qin Dynasty, migrated ever southwards as they escaped from conflict and disasters, and their kung fu has followed the same journey.

“You see more of the martial arts [of the Hakka people] in the walled villages than in the wuguans,” says Fu Tin-son, a master of the Jiangxi Bamboo Forest Praying Mantis faction. A wuguan is a training hall for kung fu.

Bruce Lee's legacy endures even 50 years after his death

Wong, Lai and Fu all belong to the Hakka Kung Fu Culture Research Society, which has supported the City University of Hong Kong in the completion of a project titled “Hong Kong Martial Arts Living Archive”.

Nineteen masters from various factions of kung fu took part in the project over the course of three years, which uses stereoscopic 3D moving image technology to capture movement, and the results are being displayed in an exhibition at the City University. The exhibition, called the “300 Years of Hakka Kung Fu: Digital Vision of Its Legacy and Future”, will run until January 4.

In capturing their movements, the masters had to wear an outfit dotted with ping pong balls as they performed their stances and strikes, and infrared rays were used to pick up the motions. It was an uncomfortable process, and the they had to repeat their moves over and over again – sometimes more than 20 times in order for them to be fully captured. However, the masters all agreed that the tedious process was worth it.

“I’m glad that there’s such a platform nowadays to preserve the kung fu styles [that are dying],” says Fu.

However, it’s likely to be a limited preservation, as Wong says that: “I doubt the future generations will be able to learn kung fu through it. You have to practise with an actual master who can explain everything to you… there might be thousands of variations of a single, simple move.”

“Kung fu is a type of art,” agrees Lai. “It comes down to your own ‘feel’ of the moves, as well as being given verbal and physical interpretation.”

How martial arts films represent Hong Kong locally and abroad

The three masters were taught martial arts by their own sifus – a skillful person or master in something, in this case kung fu. Fu says villages used to collectively hire a kung fu master to teach the young men of a village, so that they would be able to protect their tribes against beasts and other invading or rival tribes.

Wong began his martial arts journey in the 1970s, when he was still a teenager on the mainland.

“Learning kung fu was forbidden [because of the Cultural Revolution],” he recalls, “so my friends and I had to learn from our sifu in secret.”

The sifu was in his 80s by then, and he taught the teens because he didn’t want the knowledge of his faction to die with him.

The first lesson in kung fu is this: respect your sifu. It’s a rule that has caused much grief for sifus and students alike.

Fu remembers when, as a 16-year-old, he used kung fu to win a street fight. He bragged about it to his sifu, expecting praise – but was severely lectured and punished for it instead.

“[I’m] teaching you kung fu not so you can fight people… it’s so you can protect your family and your tribe – as a last resort.” He still remembers his master’s words now, more than 50 years after his scolding.

“In those days, sifus would treat their students like sons, and they had our absolute respect… but now? You practically have to beg students to learn,” says Lai.

Kung fu used to be an integral part of ancient Chinese society. It was one of the ways in which conflicts were resolved – but in our move from an agricultural society into an industrial one, kung fu has gradually lost value in the eyes of the people.

“We now look to the law to resolve arguments and conflicts, so kung fu has lost its practical value,” says Lai. He thinks the more developed society becomes, the more difficult it will be to keep kung fu alive.

“The younger generation are put off by the hard work. They already have to spend so much of their time studying and working. Where are they supposed to find the time to practise horse stances?” questions Lai. The horse stance is one of the most basic moves there is to learn, and Lai used to spend – and still does – nearly two hours a day practising just the horse stance.

“There are no short-cuts,” agrees Wong. “It takes sweat, time, and effort and it’s easy to tell whether [a student has] put in the work or not.”

Times are changing, and everything needs to change with it – even the motion capture technology has made significant progress over the three years that the Hong Kong Martial Arts Living Archive has been in developement. At the exhibition’s opening, Wong put on another outfit designed to capture his movements – one without ping pong balls, and without a need to wait for infrared rays to follow his stances and strikes. Now even the slightest movement can be captured and rendered digitally instantly. Kung fu, however, still struggles to adapt.

“It’s a pity that a lot of the factions are dying out,” says Fu, “But this exhibition means that we can at least preserve the stances.”