Behind the (pitch-black) scenes of the popstar-filled Concert in the Dark, organisers don't let disability slow them down

The power of performing in complete darkness, an assistant project manager and a stage manager explain, is that it really helps to bring emotions to the fore – both for the audience and the performers

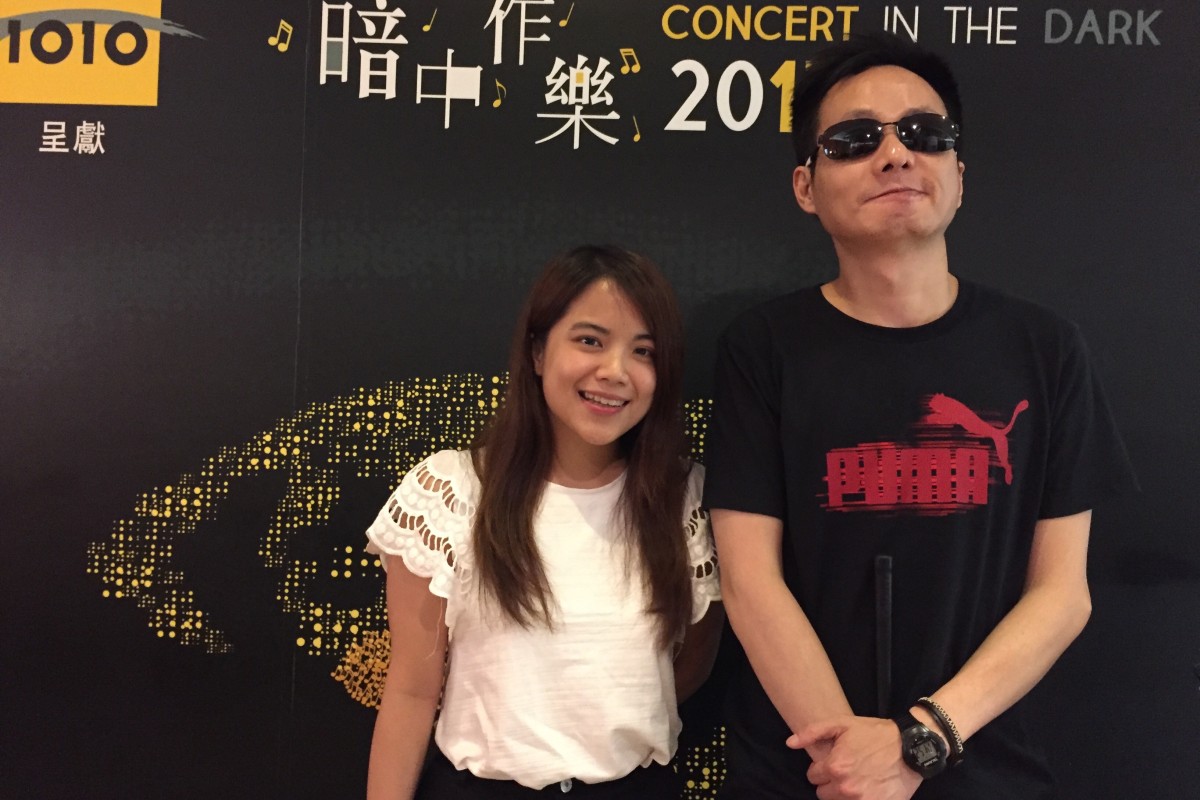

Jen Fong (left) and Sherman Yuen have tried to make CiD as good as it can be.

Jen Fong (left) and Sherman Yuen have tried to make CiD as good as it can be. Next week at the Kowloon Bay International Trade and Exhibition Centre, a concert audience will witness a show unlike any other – but just like any other show, they’ll likely never know the months of preparation, hard work and manpower that went into preparing it. Now in its seventh year, Concert in the Dark (CiD) 2017 will take place at Kitec from August 24-27. Performing artists will include at17, AGA, and Hins Cheung.

“What makes it possible is everyone doing their jobs and doing it well,” says Jen Fong, assistant project manager for CiD.

“Jen is really another stage manager,” says Sherman Yuen, Head of Dark Experience and stage manager for CiD. “Her work lifts a lot off my shoulders.”

Fong and Yuen are both heavily involved in the planning and running of the concert, and are both visually impaired.

Fong began losing her sight at a young age because of a condition that affected the retina in her eye, and is now left with less than 10 per cent of her sight. Yuen used to be a cabin crew member for Cathay Pacific, but lost his sight entirely in an accident that also left his body broken. He’s been involved in CiD since it began seven years ago, and Fong joined the team in the event’s second year.

As its name suggests, CiD is performed in complete darkness. Audience members are led into the venue and brought to their seats by staff. They cannot see each other or the performers, nor can the performers see the audience or anything else.

As stage managers for such an unusual show, Fong and Yuen’s roles cover everything from the big decisions to taking care of the minute details.

Fong says she handles more of the internal preparation – such as communicating with the human resources department and assisting on administration duties. Yuen, on the other hand, focuses his energy on collaborating with sponsors, and organising rehearsal times for performers, which requires working around their schedules. There are also smaller things that are equally as important – like making sure everyone gets their lunch.

Both agree that regardless of what they’re doing, it’s important for them to lead their team well, and as firmly and decisively as possible.

“The team needs to feel assured we know what we’re doing,” Fong stresses. Yuen agrees. “With the whole team looking to us, we can’t be the ones who are unsure.”

Of course, organising any event is a huge challenge, and there’s even more pressure when one of your five senses is compromised. Fong gets around her near-blindness by using really big fonts on her computer or using a marker instead of a pen when she’s writing. For Yuen, technology plays a huge role in helping him do his job, and he relies on apps to turn any text-based document into an audio file he can listen to.

“We handle problems the same way as everyone else – by working through or around them,” Yuen says.

It’s not just the organisers who face problems though – the performers do, too.

“It takes a lot of courage for our performing guests to take part,” Yuen emphasises. “Without the visual spectacle, the audience is much more focused on the music. A single wrong note can stand out. It’s daunting to worry about the little things you’ve never had to worry about before, from not being able to see what their hands are doing on their instruments to not being able to find the microphone.”

Conducting a concert without all the razzle dazzle you’d expect from such a show, though, has given the performers a new perspective, the duo tell Young Post.

“They’re used to responding to the audience’s reactions, but in the dark there’s nothing – they have to focus on the music. Emotions are easier to tap into in the dark,” Fong explains.

Yuen adds that, in previous years, artists have come to him after the show and told him that performing in the dark made them look more inwardly, which reminded them of the feelings they had when they first started performing. Some have even teared up at the experience.

Likewise for the audience, being deprived of their sight amplifies their thoughts and emotions, and both Fong and Yuen hopes the experience will give the public a sense of what their day-to-day lives are like. Having said that, they add, the point of the concert isn’t just about showing people what it’s like to be visually impaired.

“Hopefully, it teaches them empathy. It’s not just for the blind, but for life in general,” Fong says.

“Some people will always see the loss of something as bad,” Yuen adds. “But hopefully, through interacting with us, they can see that happiness is a choice. If we can lead fulfilling and happy lives even without something as important as sight, I hope they can learn to choose to be happy, too.”