Kamikaze survivors share stories of sacrifice, tragedy and loyalty

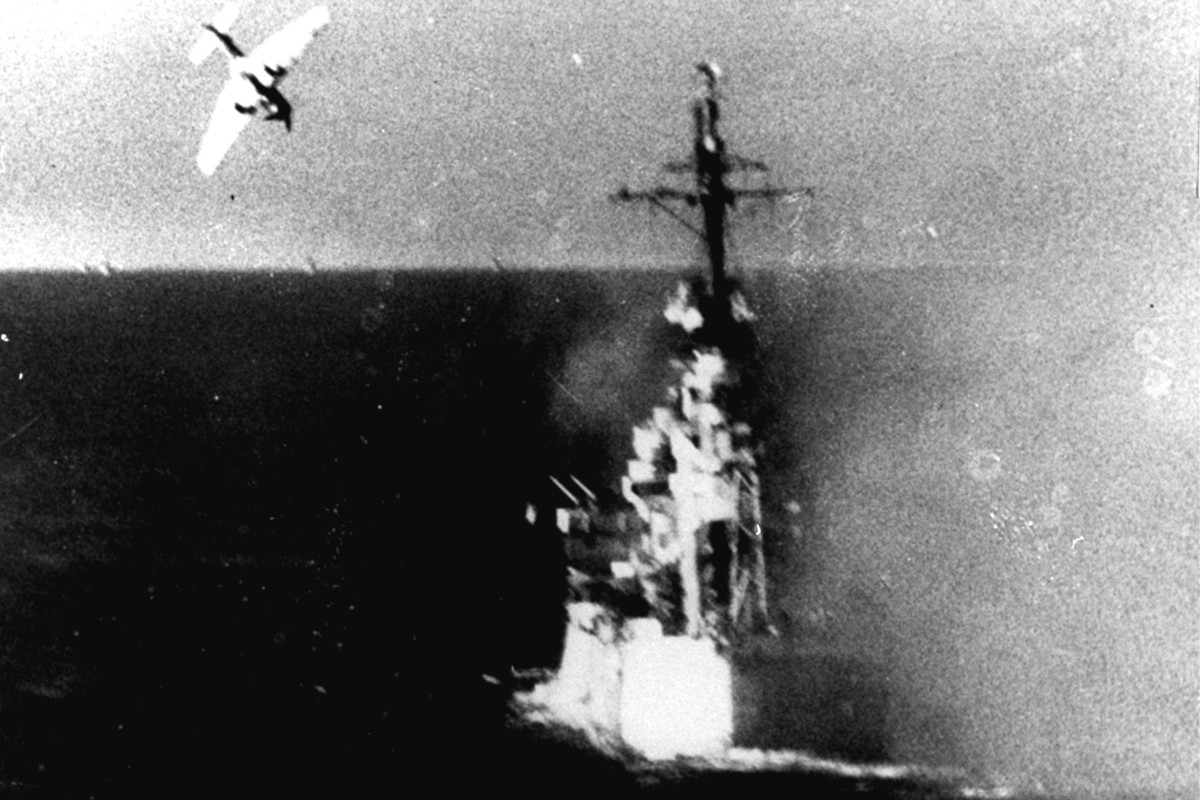

A Japanese Kamikaze fighter swoops down on a US warship during the Second World War.

A Japanese Kamikaze fighter swoops down on a US warship during the Second World War.The pilots entered the room and were given a piece of paper that asked if they wanted to be kamikaze. There were three answers: “I passionately wish to join,” “I wish to join,” and “I don’t wish to join.”

This was 1945 and now Japan was running out of troops. Hisashi Tezuka recalls taking a long time to decide and wrote his own, honest answer: “I will join.”

“I did not want to say I wished it. I didn’t wish it,” he told The Associated Press. He found out that those who picked the third choice were told to pick the right answer.

They were the kamikaze, “the divine wind,” whose job it was to sacrifice themselves by flying into enemy targets during the Second World War. It’s thought that 2,500 of them died during the war and that one in every five managed to hit his target.

Books and movies have made them look like crazed suicide bombers, but new interviews with survivors and families, as well as letters and documents, tell tales of young men who were loyal to their country.

All set to die

First-born sons weren’t selected to protect family heirs. Tezuka, then a student at the University of Tokyo, had six brothers and one sister and wasn’t the eldest. So he was a good pick, he says with a sad laugh. However, he didn’t tell his parents that he was going to be a suicide bomber.

There was one certainty about being a kamikaze, he says: “You go, and it’s over.” He survived only because Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender on the radio as he was his way to take off on his kamikaze attack.

“I had been all set to die,” he says. “My mind went absolutely blank.”

He was 23. Now, at 93, he notes that he has lived four times as long as many kamikaze.

He loved flying the Zero fighter planes so much so that he didn’t want to fly passenger aircraft afterwards. He was so sick of war that he didn’t want to join the military, so he started an import business instead. He often visited American farmers, but never told them he had been a kamikaze.

Flicking through photos, Tezuka remembers the white silk scarf the Zero fighters wore. “That’s to keep warm. It gets really cold up there,” he says.

He recalls his training and how it was easy to forget the war while flying over forests and lakes. “Do you know what a rainbow looks like when you’re flying?” he asks excitedly. “It’s a perfect circle.”

Pilots’ sweethearts

Zero pilots were the heartthrobs of the era. In fading photographs, they smile alongside their comrades and seem oblivious to what lay ahead. Their goggles are flipped over their helmets and their scarves are tucked under their jackets.

Masao Kanai died on a kamikaze mission near Okinawa in 1945 aged 23. Japan created a program to encouraged students to support the imperialist military by writing letters and he had been pen pals with a 17-year-old schoolgirl, Toshi Negishi. All in all, they exchanged 200 letters.

They tried to go on a date, just once, when he had a rare break from training and visited Tokyo. But that was on March 10, 1945, right after the massive air raids known as the firebombing of Tokyo. So the two never met.

Before he flew on his last mission, he sent her two tiny pendants he had carved out of cockpit glass — one a heart carved with the initials T and M, the other a tiny Zero.

Negishi kept the pendants for 70 years before donating them to a memorial for the Tsukuba Naval Air Corps, a command and training centre for kamikaze in Kasama, north of Tokyo. There are plans to tear down the buildings from that period, but volunteer members of the community are trying to preserve it.

“Someone has to remember. It hurts too much if we don’t,” Negishi says in a film made by the volunteers.

They have put up an exhibition of photos, letters, helmets, pieces of the Zero and other remnants from that period. Included in the collection is Kanai’s final letter to his family: “I don’t know where to begin,” he wrote. “Rain is falling softly. A song is playing quietly on the radio. It’s a peaceful evening. We’ll wait for the weather to clear up and fly on our mission. If it hadn’t been for this rain, I’d be long gone by now.”

One of the eeriest photos on display is a woman wearing a bridal kimono, sitting with her family and holding a framed picture of her dead fiance, Nobuaki Fujita, a kamikaze. The bride, Mutsue Kogure, stares blankly into the camera.

In the last letter he wrote to her Fujita says “In my next life, and in my life after that, and in the one after that, please marry me,” he wrote. “Mutsue, goodbye. Mutsue, Mutsue, Mutsue, Mutsue, the ever so gentle, my dearest Mutsue.”

A survivors’ guilt

In training, the pilots would zoom straight down to practice crashing. They had to pull up before hitting the ground, and experience extreme G-force. When they did it for real, they had to send a final message in Morse code, and keep holding that signal. In the transmission room, they knew the pilot had died when a long beep ended in silence.

Yoshiomi Yanai, 93, survived because he could not locate his target and often visits the Tsukuba facility to pay his respects to his comrades. “I feel so bad for all the others who died,” he says.

Yanai has a photo album that he made to his parents. The pages are full of happy photos, drawings and the message: “Father, Mother, I’m taking off now. I will die with a smile … And I will be waiting for you.”

Maxwell Taylor Kennedy, who wrote a book, Danger’s Hour, about the kamikaze, says they were driven by nothing but self-sacrifice. He found they were very much like Americans or young people anywhere else in the world, but that were different suicide bombers today because they didn’t target civilians.

“They were looking out for each other,” he says. “If he didn’t get in the plane that morning, his roommate would have to go.”

Killing with a pencil

Another plane - the Ohka - was more suited to kamikaze missions because it was small and packed with bombs. They were taken near the targets, hooked on to the bottom of planes, and then let go.

Ohka means “cherry blossom”, but the Americans called it the “Baka bomb”, using the Japanese word for “idiot”, because they were easily shot down.

The man in charge of the Ohka pilots and ultimately sending them to death was Fujio Hayashi, then 22. He was one of the first volunteers for Ohka, but he wonders whether the strategy would have happened if no-one had volunteered when it was first suggested. He says that the first time he saw one of the flimsy gliders, many thought it looked like a joke. As a result, he felt guilty for sending dozens of young men to their deaths. He sent his favourite pilots first to show that he had no favourites.

“Every day, 365 days a year, whenever I remember those who died, tears start coming. I have to run into the bathroom and weep. While I’m there weeping, I feel they’re vibrantly alive within my heart, just the way they were long ago,” he wrote in his essay “The Suicidal Drive.”

After the war, Hayashi joined the military and attended memorials for the dead pilots. He consoled families and told everyone how gentle the men had been. They smiled right up to their deaths, he said, because they didn’t want anyone to mourn or worry.

Hayashi hardly talked about his kamikaze days to his children. They remember him as a dad who loved classical music, took them to amusement parks and loved cats.

“I think of the many men I killed with my pencil, and I apologise for having killed them in vain,” he said, referring to how the names of the pilots were written each day. He said that, for him, the war would only be over when his ashes were scattered into the sea near the southern islands of Okinawa, where his men had died.

He died of pancreatic cancer at age 93 earlier this month, and his family plans to honour his request.