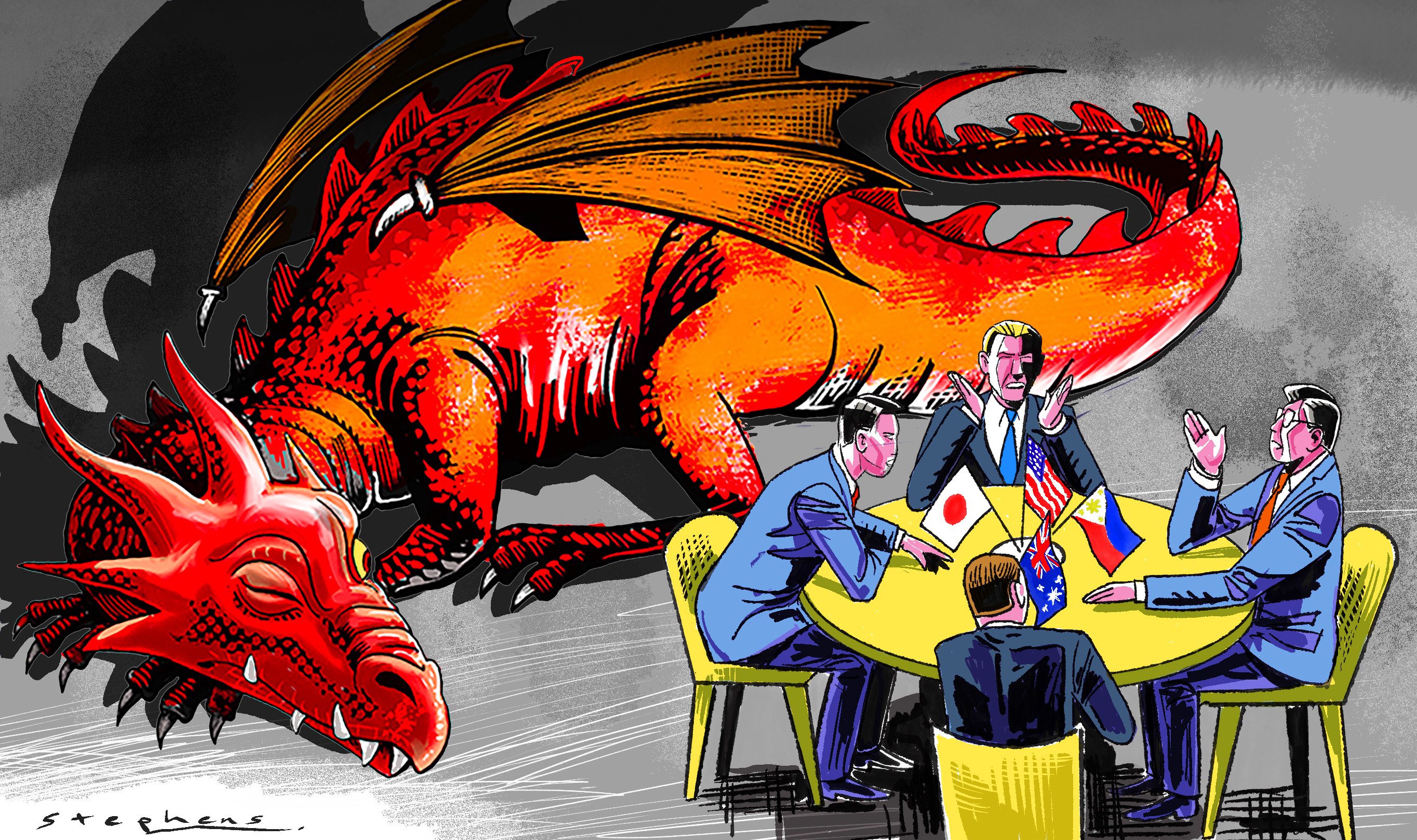

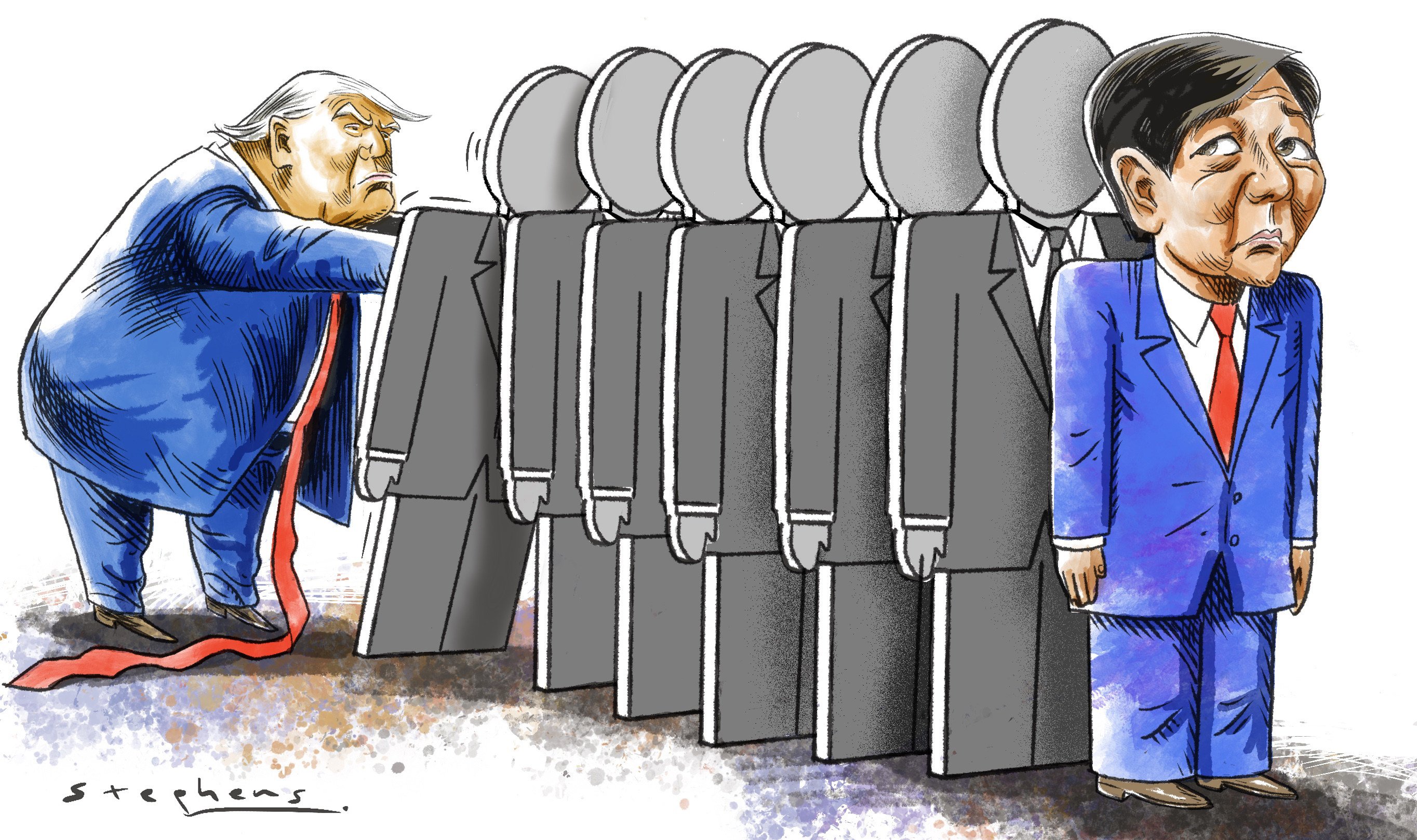

Keeping US allies onside means rolling back tariffs and coming up with a long-term strategy, both of which are counter to Trump’s strengths.

2 Dec 2025 - 9:30PM videocam

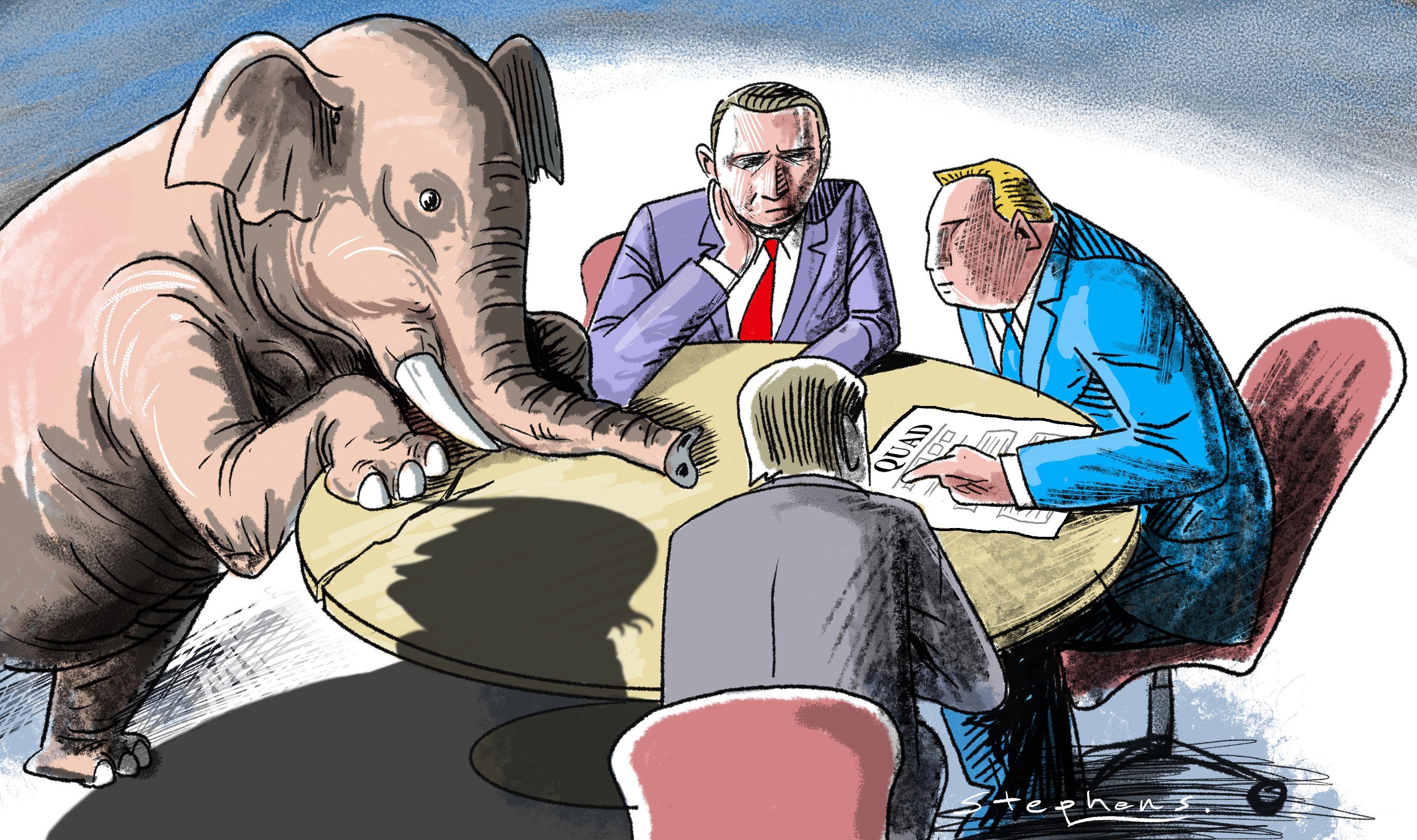

Uncertainty surrounds the ‘Squad’, including the US’ ability to support another grouping and Trump’s push for a grand bargain with China.

14 Nov 2025 - 8:30PM videocam

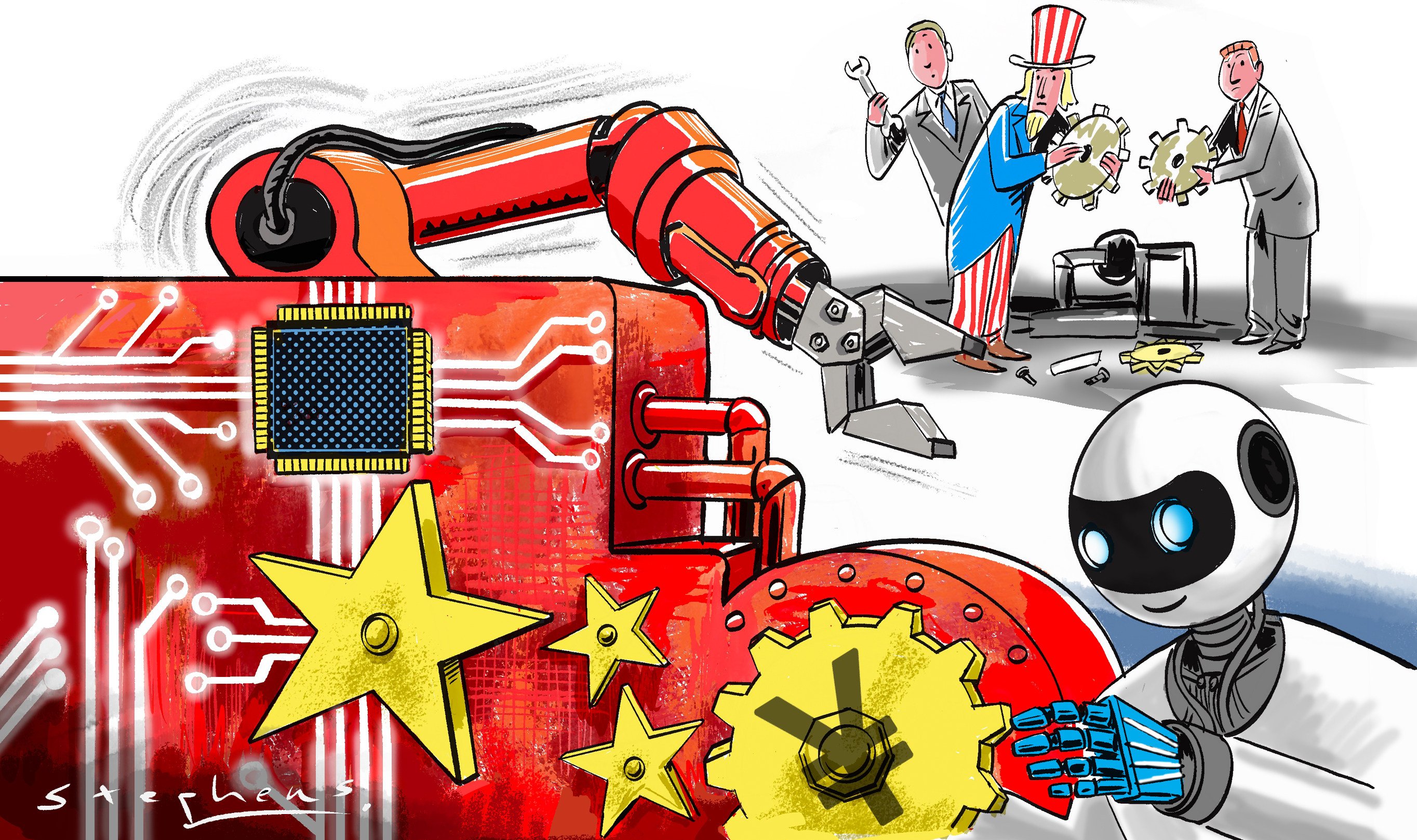

‘Made in China 2025’ has helped Beijing increase its level of self-reliance and severely dented the global appeal of free-market economics.

28 Oct 2025 - 8:30PM videocam

As Washington pushes New Delhi closer to Beijing, both Asian powers must exercise strategic patience for an effective detente.

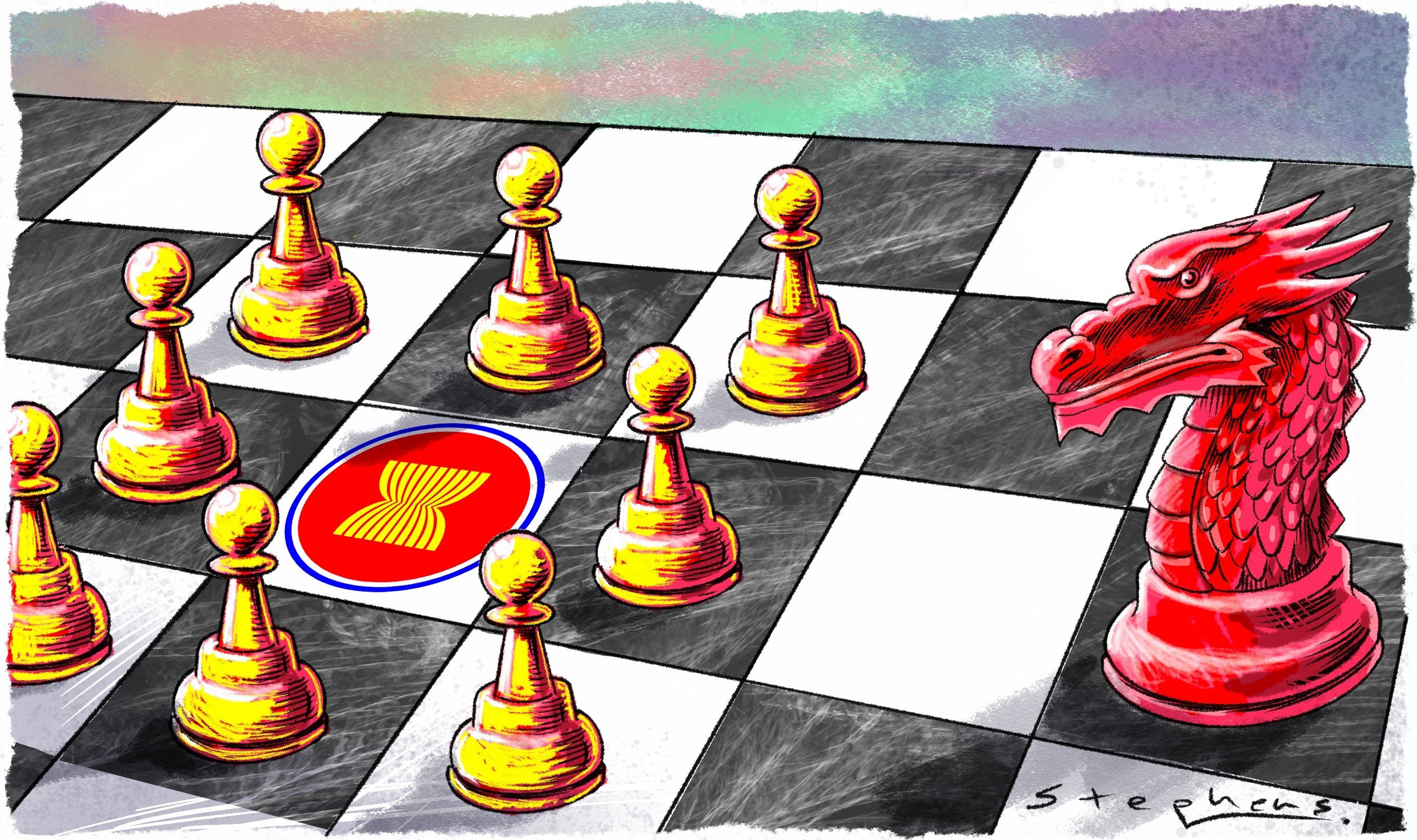

By reducing dependence on the US and enhancing ties among each other, like-minded middle powers are better able to set their own terms.

25 Sep 2025 - 8:30PM videocam

The world is desperately seeking leadership to uphold a rules-based order. China is well equipped to provide an alternative to the US.

16 Aug 2025 - 5:30AM videocam

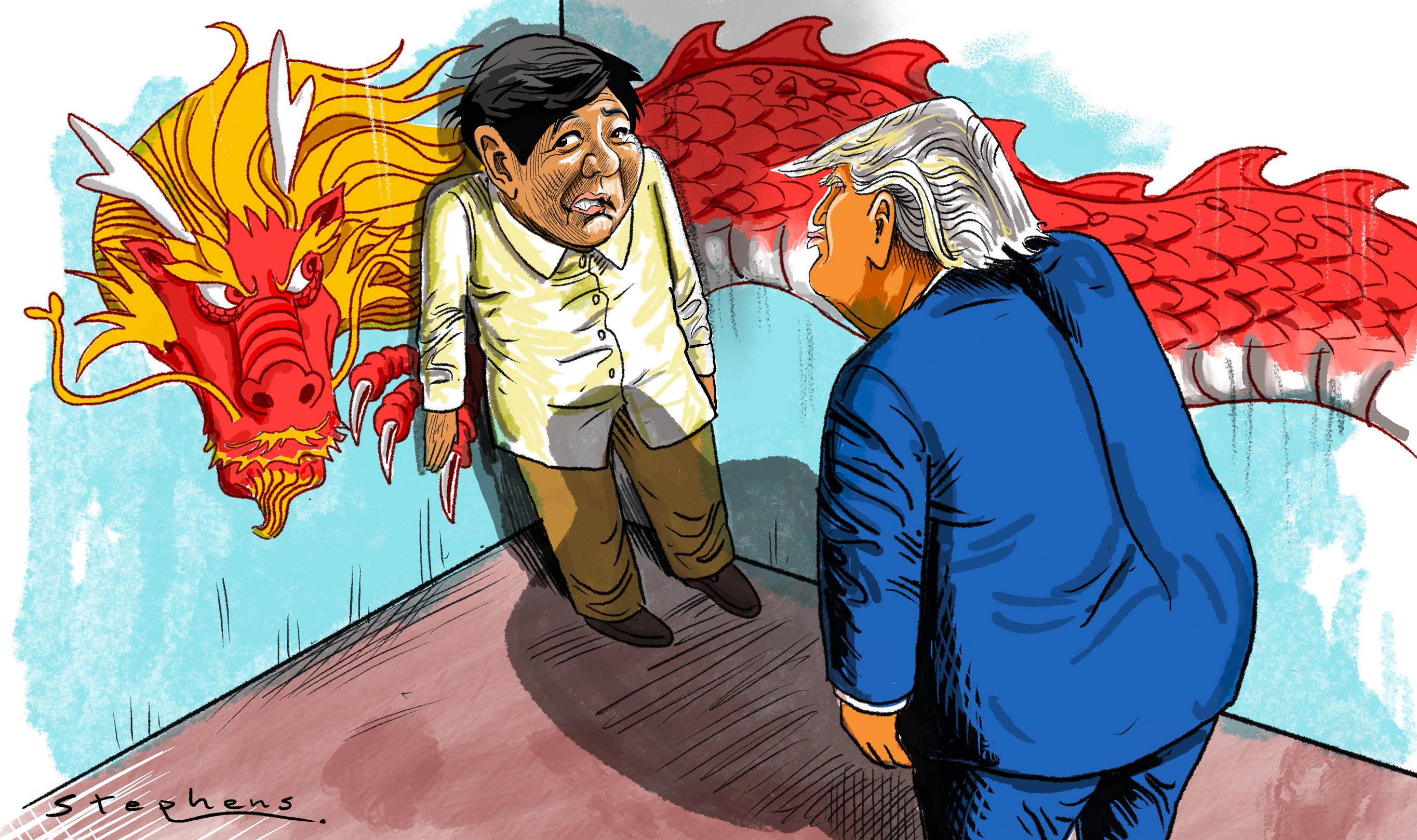

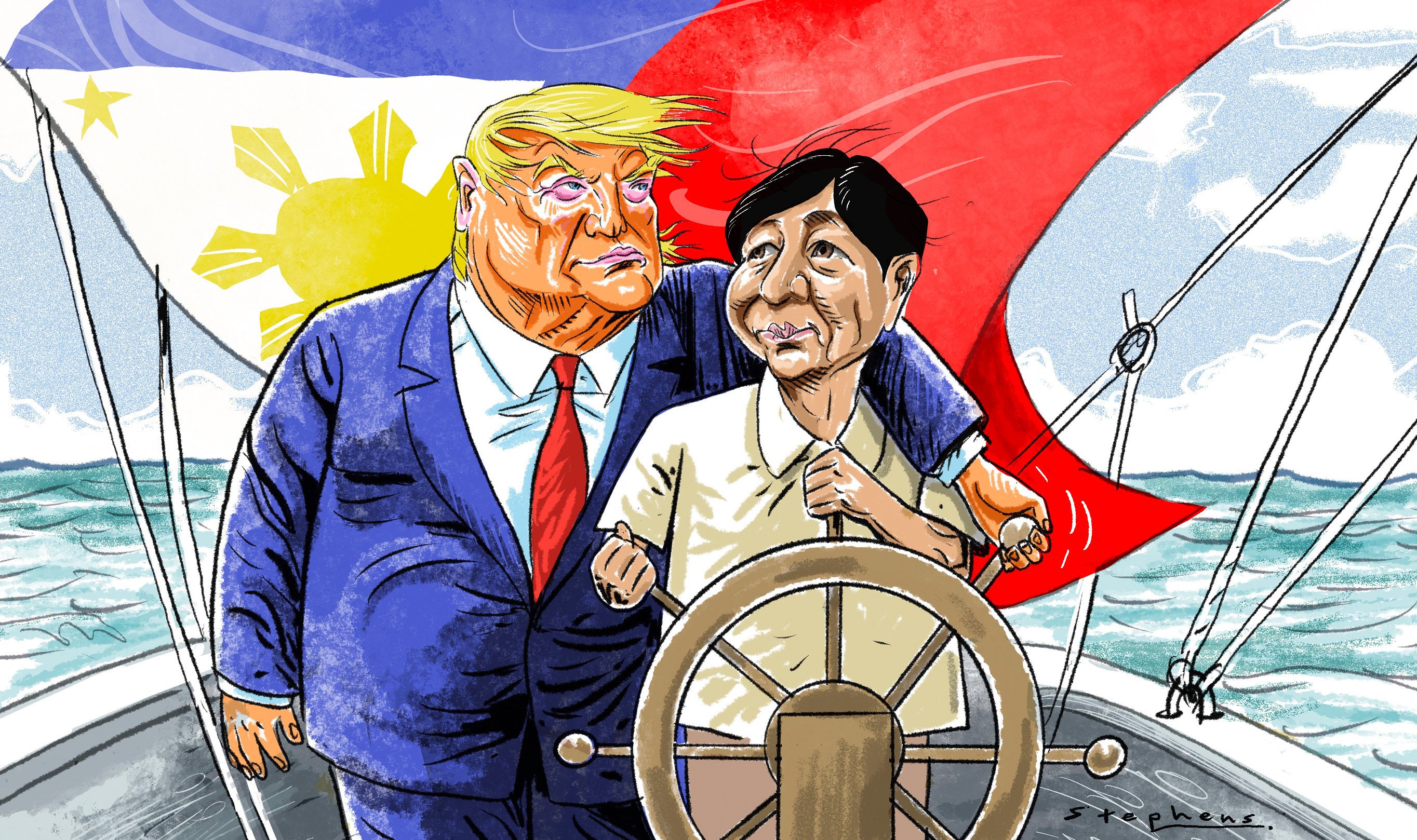

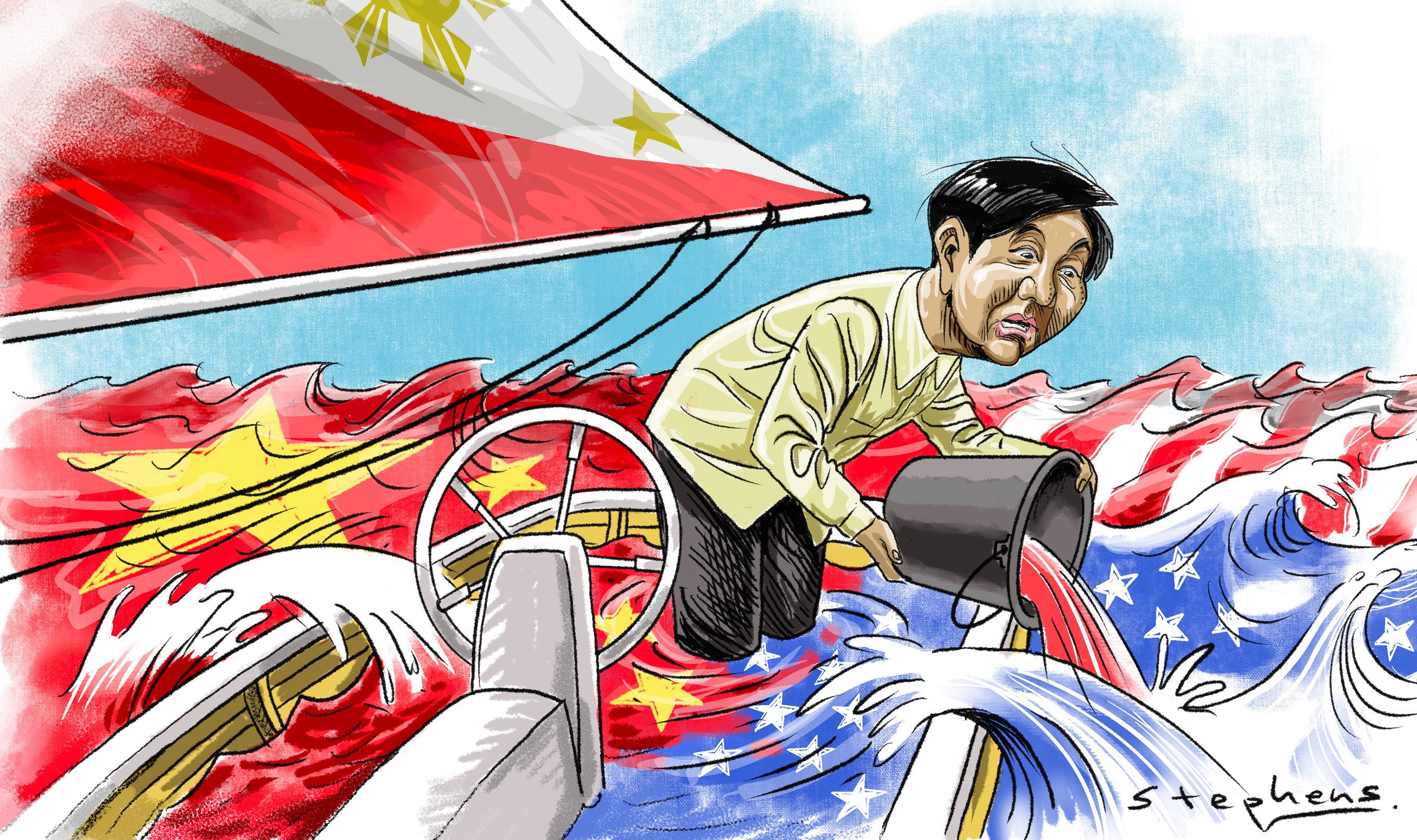

Marcos’ goal of a balanced foreign policy is at odds with efforts to further intertwine the US and the Philippines in the security sphere.

14 Jul 2025 - 7:38AM videocam

For all his bluster, he has failed to broker peace in Ukraine even as Israeli strikes dashed any chance of a nuclear deal with Iran.

20 Jun 2025 - 6:41AM videocam

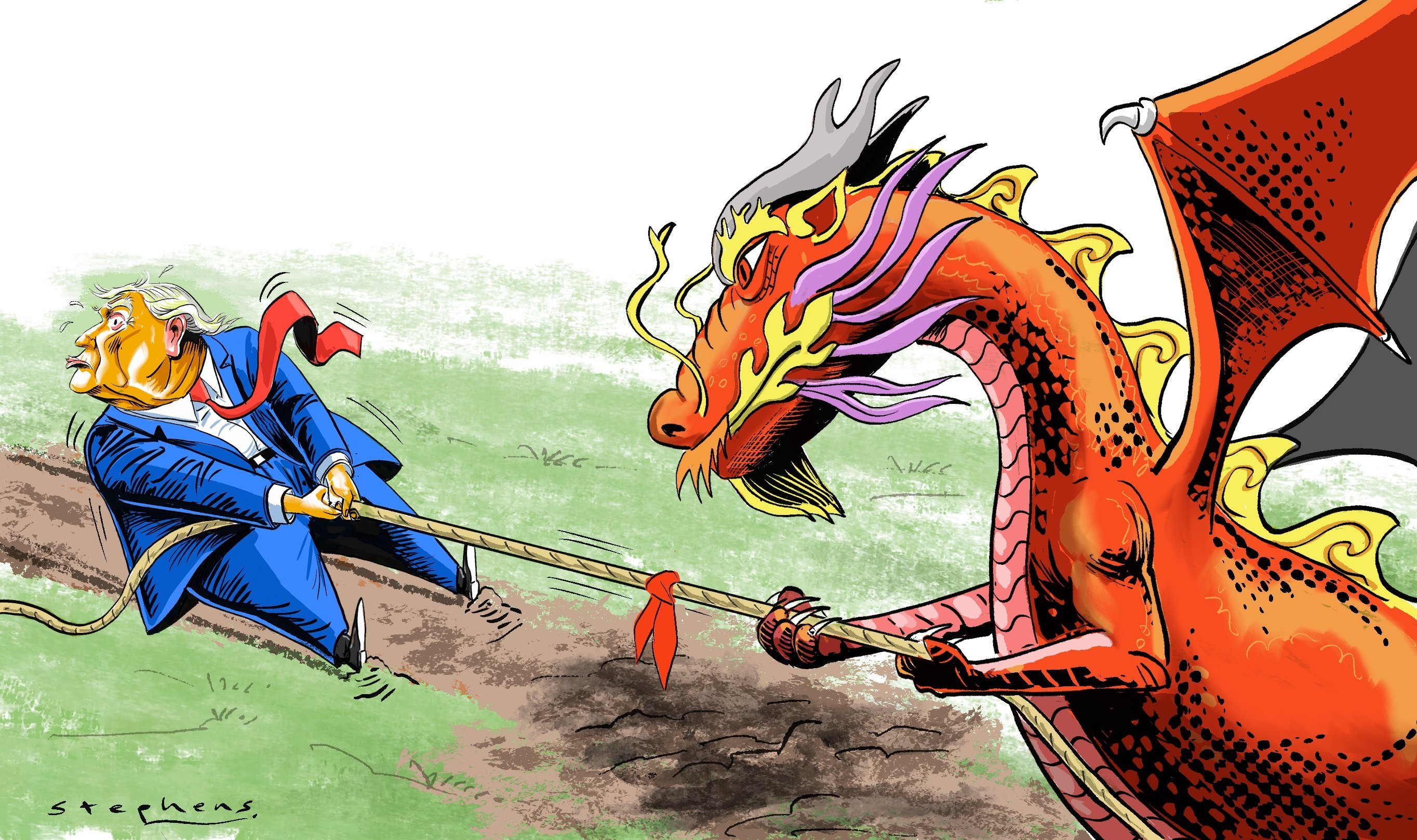

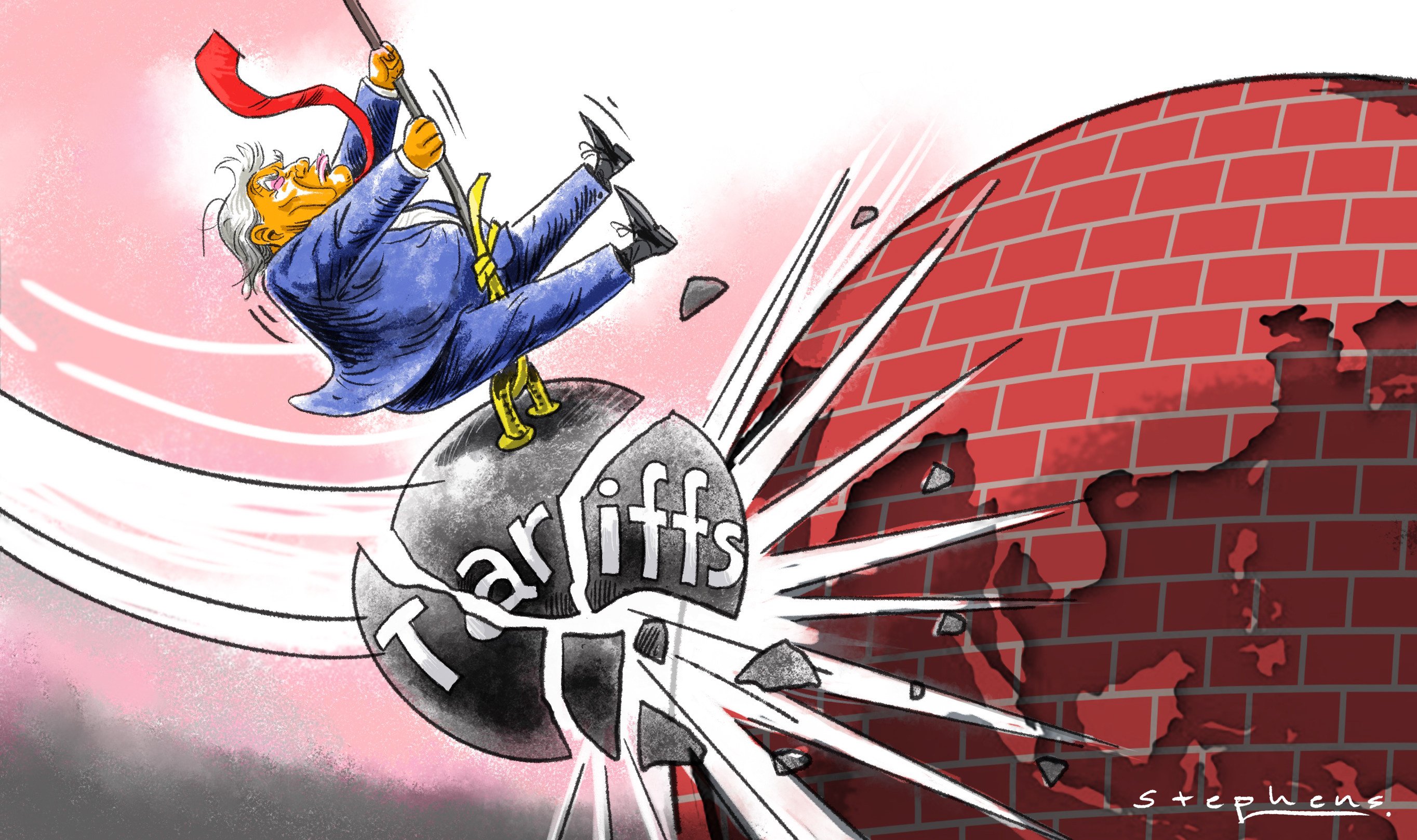

Even if there is a clear motivation in Trump’s deglobalisation push, poor tactical execution can ruin even the soundest strategic objectives.

3 Jun 2025 - 6:34AM videocam

Despite diplomatic and ideological differences, the EU and Southeast Asia’s trade and defence needs are bringing the two sides together.

19 May 2025 - 8:30PM videocam

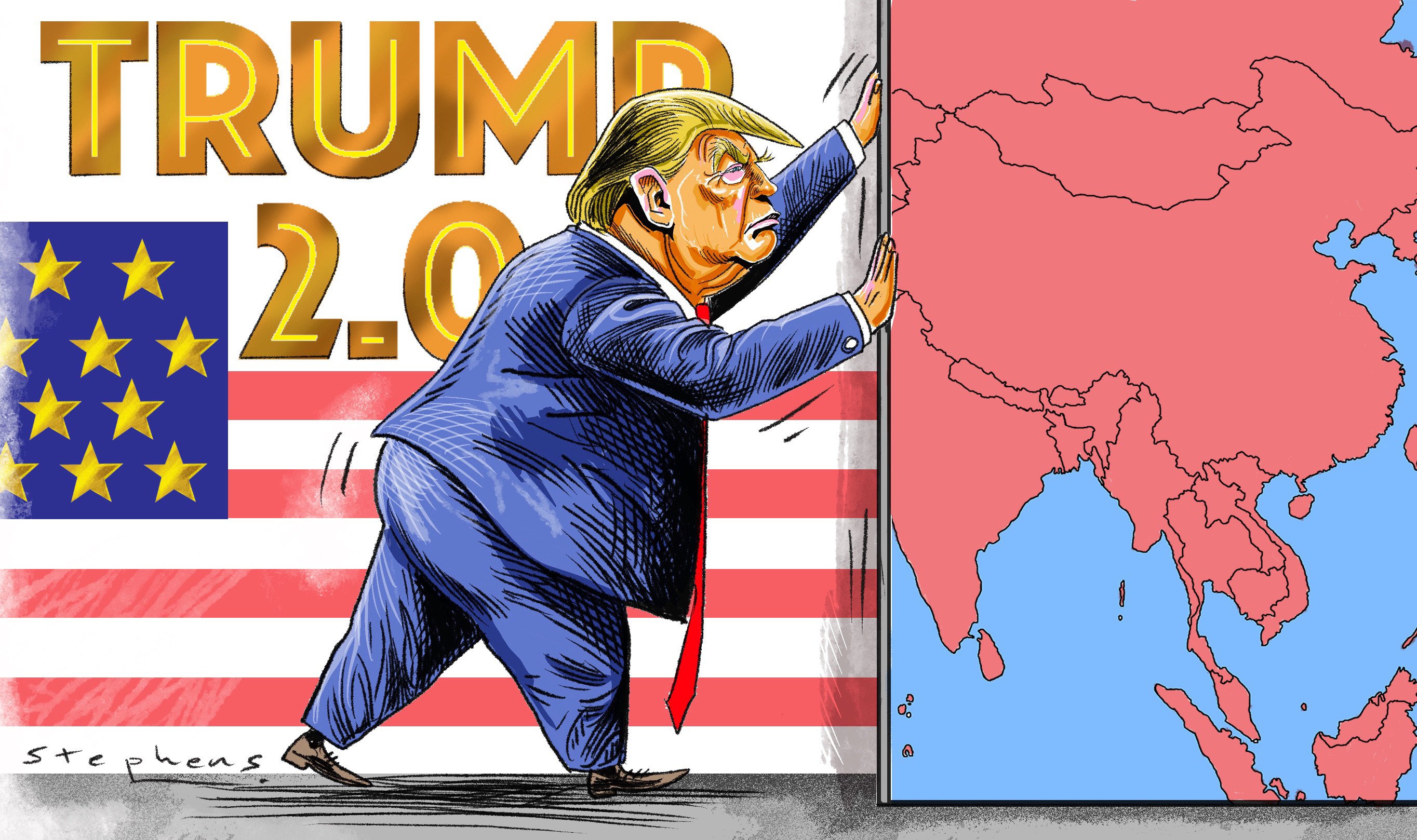

China’s message of stable cooperation is resonating as Trump accelerates the birth of a post-US world with rising powers independent of US whims.

28 Apr 2025 - 5:30AM videocam

The Trump administration has offered reassurances to Manila, but mixed signals and global tariffs mean there are still reasons to be wary.

4 Apr 2025 - 6:58AM videocam

The second Trump administration’s actions show Manila the urgent need to be more self-reliant and seek other potential defence partners.

15 Mar 2025 - 5:30AM videocam

Collective bargaining may be the only defence against his flirtation with rival superpowers, protectionist policies and transactionalist diplomacy.

4 Mar 2025 - 8:30PM videocam

If Washington uses Manila as a pawn in a ‘grand bargain’, Marcos should seek his own strategic deals with US rivals like China.

16 Feb 2025 - 10:41AM videocam

Losing the power balance in a potentially rancorous cabinet or failing to win over Asia’s rising non-aligned powers would trip up his plans.

26 Jan 2025 - 8:31PM videocam

The removal of the Dutertes from the security council is a calculated move by Marcos Jnr to prevent the family, perceived as pro-China proxies, from exerting influence.

11 Jan 2025 - 5:51AM videocam

US dominance is pervasive but not infallible, and a divided Brics can still find common ground in the pursuit of a multipolar global order.

As Russia seeks Global South partners and the war in Ukraine drags on, Southeast Asian states are rekindling ties with the Kremlin.

Nothing less than the country’s strategic autonomy as a sovereign nation is at stake as the Marcos administration faces Trump 2.0.

28 Nov 2024 - 5:30AM videocam

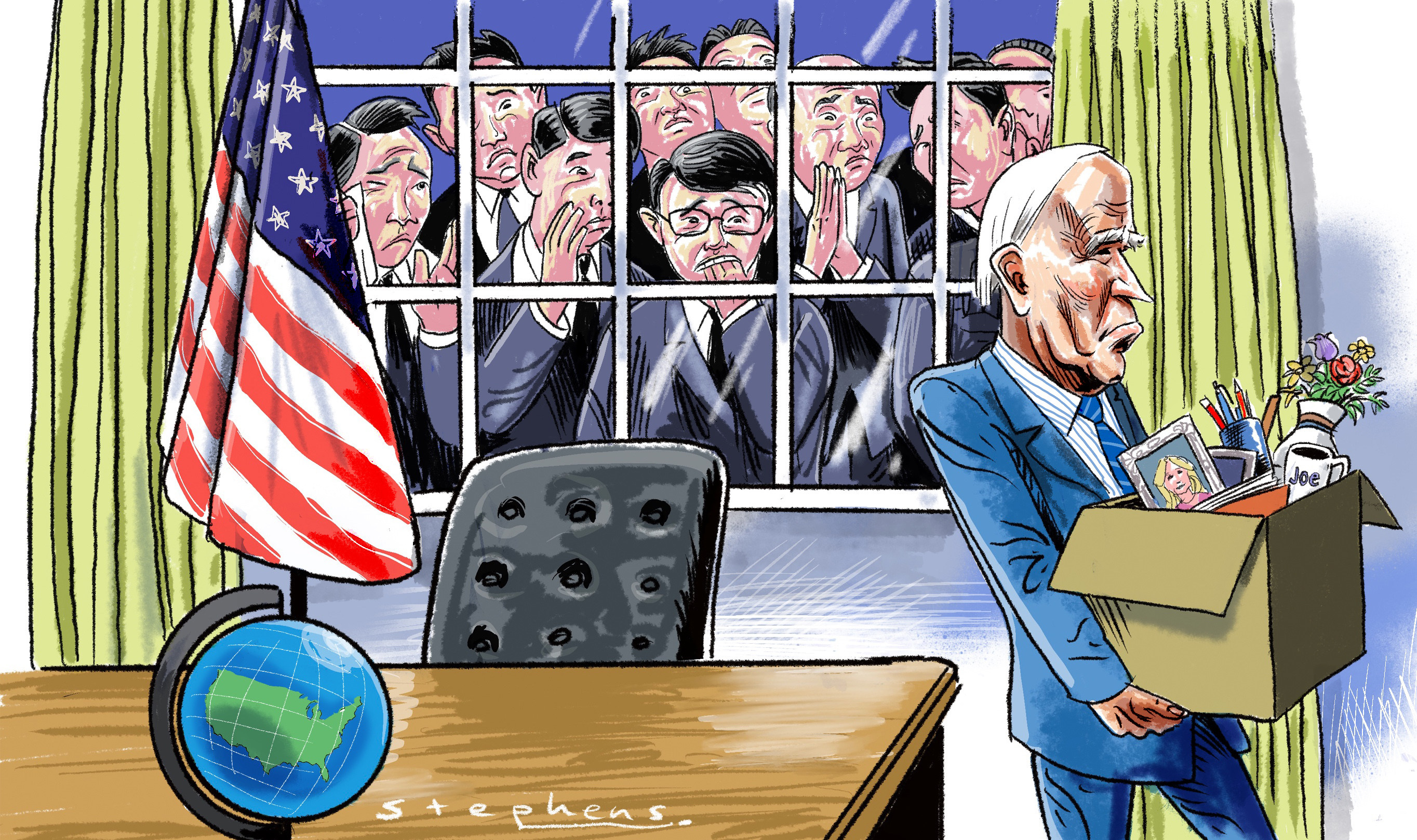

Despite Trump positioning himself as a peacemaker, his foreign policy agenda is likely to push allies in Asia further away.

13 Nov 2024 - 5:30AM videocam

The Biden administration’s repeated missteps have dealt a big blow to US standing in the region and given Beijing an opportunity to exercise its global influence.

31 Oct 2024 - 7:16AM videocam

Southeast Asian nations may take different tacks on China, but they share an interest in cooperating to defend their core interests.

14 Oct 2024 - 8:35AM videocam

The grouping’s members are pulling in different directions, and a second term for Donald Trump might upend America’s values-based global strategy.

29 Sep 2024 - 9:59PM videocam

As tensions with China escalate, Philippine strategists are divided on how to protect the Southeast Asian nation’s maritime security.

17 Sep 2024 - 9:24AM videocam

Domestic issues tend to top Philippine voters’ concerns, but recent events could make Ferdinand Marcos’ foreign policy a decisive factor.

28 Aug 2024 - 12:00AM videocam

Instead of aligning with one superpower against another, the Philippines is bent on enhancing its own strategic agency in world affairs.

15 Aug 2024 - 10:21AM videocam

Whether Trump or Harris wins, Biden’s departure will mark the end of an era of distinctly multilateral American leadership

27 Jul 2024 - 5:53AM videocam

Calls in the Philippines are growing, for measures from building a lighthouse on Second Thomas Shoal to inundating China with litigation.

13 Jul 2024 - 6:03AM videocam

Dithering official statements reflect not only Philippine fears of unwanted escalation but also, crucially, doubts over US defence commitments.

29 Jun 2024 - 6:39AM videocam