75 years later, Japan’s second world war orphans talk about their pain and recovery

- For years after the end of the Pacific War, children who lost their parents were bullied and abused by relatives, the government and society

- They were sent to orphanages or jail and often lived on the streets, forced to steal to survive

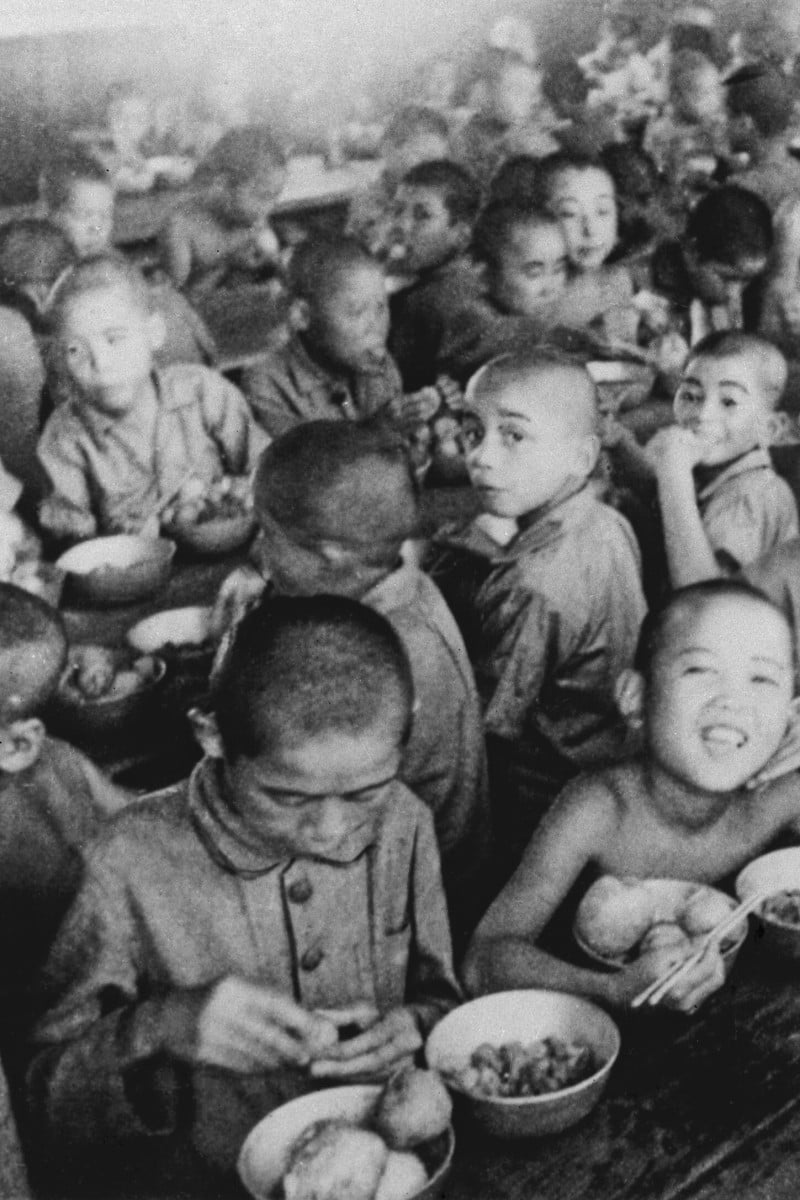

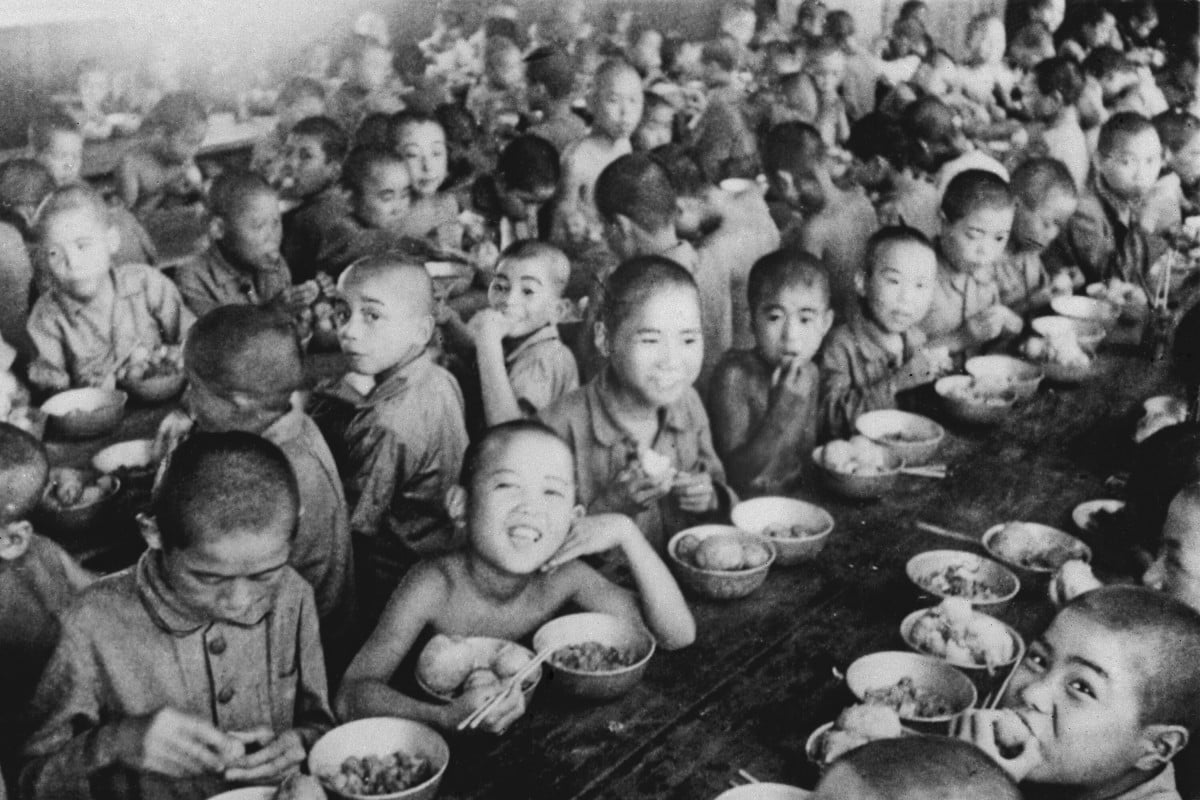

War orphans eat together at an orphanage in Tokyo in 1946. In Japan, war orphans were punished for surviving. They were bullied. They were called trash, sometimes rounded up by police and put in cages. Some were sent to institutions or sold for labour. They were targets of abuse and discrimination. A 1948 government survey found there were more than 123,500 war orphans nationwide. But orphanages were built for only for 12,000, leaving many homeless. (Kyodo News via AP)

War orphans eat together at an orphanage in Tokyo in 1946. In Japan, war orphans were punished for surviving. They were bullied. They were called trash, sometimes rounded up by police and put in cages. Some were sent to institutions or sold for labour. They were targets of abuse and discrimination. A 1948 government survey found there were more than 123,500 war orphans nationwide. But orphanages were built for only for 12,000, leaving many homeless. (Kyodo News via AP)For years, orphans in Japan were punished just for surviving the war.

They were bullied. They were called trash and left to fend for themselves on the street. Police rounded them up and threw them in jail. They were sent to orphanages or sold for labour. They were abandoned by their government, abused, and discriminated against.

Their ordeal continued even after August 15, 1945, when Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allied forces, ending the second world war, the deadliest conflict in history.

5 things to know about the world’s first nuclear attack

Now, 75 years later, some have broken decades of silence to describe for a fast-forgetting world their sagas of recovery, survival, suffering – and their calls for justice.

These stories underscore both the lingering pain of the now-grown children who lived through those tumultuous years and what activists describe as Japan’s broader failure to face up to its past.

When bombs rained down

Kisako Motoki was 10 when US cluster bombs rained down on her downtown Tokyo neighbourhood.

For decades she kept silent about the misery that followed.

On March 10, 1945, as the napalm-equipped bombs turned eastern Tokyo into a smouldering field of rubble, Motoki and her little brother hid inside a shelter her father had dug behind the family home.

She eventually fled with her brother. She never saw her parents again.

Kisako Motoki, 86, speaks, looking though a red cellophane depicting what she saw the atmosphere of the night of the Great Tokyo Air Raid on March 10, 1945. Photo:AP

The children walked together by heaps of charred bodies. They saw people with severe burns slumped on the roadside, people with intestines hanging from their stomachs. She blamed herself for not waiting for her parents. She believed she’d caused their deaths.

Motoki went to her uncle’s home, and this marked the beginning of her years-long ordeal as a war orphan.

She’d survived what’s considered the deadliest conventional air raid ever. More than 105,000 people were estimated killed in a single night, but the devastation was largely eclipsed by the two nuclear bomb attacks and then forgotten during Japan’s post-war rush to rebuild.

As a schoolgirl, Motoki worked as a maid for her uncle’s family of 12; they paid for her schooling in return. She was verbally abused, and her cousins repeatedly beat her brothers until their cheeks were swollen and bruised. They all ate only once a day.

One Hongkonger’s story about life during the Japanese occupation

Motoki says her relatives, like tens of thousands of others, were struggling to rebuild their lives. They had little time to spend on orphans, even blood relatives. The government gave them no support.

“It’s very painful for me to tell my story,” she said. “But I still have to keep speaking out because I feel strongly that no children should have to live as war orphans as I did.”

Many other orphans don’t talk because of intense shame.

“How could we, as children, have spoken up against the government?” she said. “They abandoned us, and acted as if we never existed.”

After years of pain, Motoki entered university to pursue her dream of studying music. She was 60.

War orphans sell ice candy near Ueno station in Tokyo. Photo: AP

Explosion of nationalism

Mitsuyo Hoshino, 86, recalls the explosion of nationalism in November 1940, when Japan’s wartime government staged a massive imperial celebration.

During the war, Japanese schoolchildren were taught to revere the emperor as a god and devote their lives to him.

On that November day, Hoshino stepped out of her parents’ noodle shop in Tokyo’s downtown Asakusa neighbourhood and watched as huge crowds of people waved Rising Sun flags. A decorated tram clanged by, with banners glorifying the emperor and celebrating Japan’s prosperity and expansion.

A year later, on December 8, Japan attacked Pearl Harbour.

WWII refugees tell displaced Syrians not to give up hope

She remembers playing with her little sister outside the now-vanished noodle shop. She remembers a family excursion to a department store. These were her last happy childhood memories.

She was 13.

Hoshino and her classmates evacuated to a temple in Chiba, outside Tokyo, in 1944, when US firebombings escalated. She later learned from her uncle that her parents and two siblings died in the March 10, 1945, firebombing.

Hoshino and her two younger siblings were sent to a succession of relatives. She escaped one time with her siblings from an aunt’s house, afraid they were going to be sold to people needing workers and went to their grandmother’s home.

Mitsuyo Hoshino, 86, who lost her parents and siblings to the Great Tokyo Air Raid on March 10, 1945, speaks on her experience during an interview with the Associated Press at the Centre for the Tokyo Raids and War Damage. Photo: AP

She later lived with another uncle’s family, helping out on their farm while finishing secondary school.

When she was grown, she returned to Tokyo, but she struggled with discrimination in getting jobs. She heard her husband’s relatives hissing about her “dubious background” at their wedding ceremony.

Much later, she decided to share her experiences by drawing for children, eventually compiling a book of 11 orphans’ stories, including her own.

One of those orphans, when asked what she’d wish for if she could use magic, simply says: “I want to see my mother.”

Abusive relatives

A 1948 government survey found there were more than 123,500 war orphans nationwide. But orphanages were built for only 12,000, leaving many homeless.

Many children escaped from abusive relatives or orphanages and lived at train stations, earning money by polishing shoes, collecting cigarette butts or pickpocketing. Street children were often rounded up by police, sent to orphanages or sometimes caught by brokers and sold to farms desperate for workers, experts say.

The stories of the war orphans highlight Japan’s consistent lack of respect for human rights, even after the war, said Haruo Asai, a Rikkyo University historian and an expert on war orphans. US forces during their seven-year occupation of Japan also looked the other way on orphans, Asai said.

Teens and military vets swap stories during Covid-19

Victims of war

More than 2,500 children of about 400,000 Japanese – many of them families of Imperial Army soldiers, Manchurian railway employees and farmers who had emigrated to northern China, where Japan established a wartime puppet state – were displaced or orphaned.

Xi Jingbo’s parents were Japanese, but he had no official record of his place and date of birth. Villagers told him he was left behind when the Japanese fled after the surrender. He and his adoptive parents didn’t discuss the sensitive issue.

“We are the victims of the war,” he said. “All Chinese are victims, and so are the Japanese civilians.”

A retired secondary school maths teacher and principal, Xi says he was well cared for by his Chinese parents and suffered no discrimination. He took care of them as they aged. After the last one died in 2009, Xi started making annual short visits to Japan.

Sober-faced young Japanese war orphans from Manchuria arrive in Tokyo, Japan, and walk double-file across a railroad station platform. A 10-year-old girl, Ishiko Hosoda, (right foreground) carries the ashes of her brother and mother, all of whom died in Manchuria. Her father is a prisoner of war of the Red Army in Siberia.

Forgotten by history

Survivors of the firebombings and orphans feel they were forgotten by history and by their leaders.

Post-war governments have provided an accumulated total of 60 trillion yen (HK$4.37 trillion) in welfare support for veterans and their bereaved families, but nothing for civilian victims of firebombings, although Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors receive medical support.

Mari Kaneda, 85, says the firebombing changed her life, forcing her to live under harsh conditions with relatives. She suffered lifelong pain and stigma for being an orphan, and had to abandon her childhood dream of becoming a schoolteacher.

Kaneda was nine when she stepped off a night train in Tokyo after riding from Miyagi, in northern Japan, where she evacuated with her class. She had missed by hours the attack that killed her mother and two sisters and destroyed the family store.

Japan’s government has rejected redress for civilian victims of firebombings. But Kaneda, in her search for justice, has dug up post-war government records, interviewed dozens of her peers and published a prize-winning book on war orphans.

“I haven’t seen anything resolved,” Kaneda said. “To me, the war has not ended yet.”