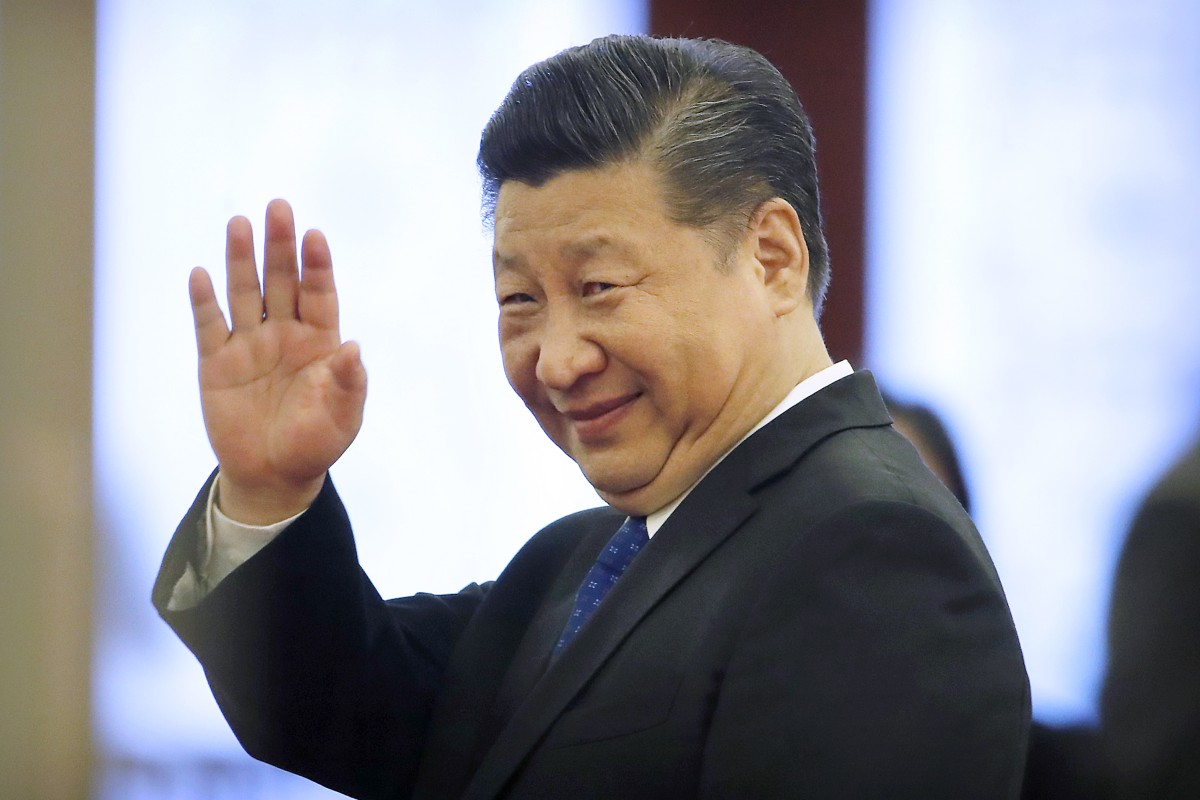

What are the geopolitical implications behind Xi Jinping's meeting with Kim Jong-un?

Why does China seem to get into so many disputes? Geography may be a huge part of the answer

Xi Jinping's meeting with Kim Jong-un may have been a clever foreign policy move.

Xi Jinping's meeting with Kim Jong-un may have been a clever foreign policy move.North Korean leader Kim Jong-un has been dubbed an “astute leader” for his international debut in Beijing last month. The apparently amicable meeting, with Kim claiming to feel obliged to “congratulate Xi in person” on his re-election, was said to have brought Kim more bargaining power ahead of his planned summit with US President Donald Trump.

According to analysts, the young Korean president, whose country has faced crippling sanctions for conducting nuclear and missile tests since he came to power in 2011, may have been trying to gain advantages from China.

But why would President Xi Jinping, leading a nation projected to soon overtake the US as the world’s largest economy, entertain a figure who has contributed to so much regional tension?

Some suggest that, amid planned talks between Trump and Kim, Xi does not want to be sidelined on the Korean issue, especially since China is preparing for a possible trade war with the US. Yet seeing the Xi-Kim meeting as merely a response to recent international political developments would be ignoring the geopolitical implications behind Chinese foreign policy.

China has been working to secure its borders and, more importantly, access to shipping lanes in the South China Sea and the Pacific Ocean. Beijing’s disputes with neighbouring countries, including Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines, aren’t just military bravado and a display of national pride.

The fact is, if other countries claim these scattered archipelagoes, then Chinese ships would have to pass through foreign territories before entering the Pacific Ocean. While this may seem to be insignificant in times of peace, a regional conflict could completely change that scenario. Then China could easily face a blockade and be deprived of access to valuable resources and trade.

North Korea, which shares a 1,400km-long border with China, must not fall under the influence of Japan, or worse, the US, which would only further increase that risk.

If one understands these geopolitical implications, it becomes clear why Taiwan and Tibetan autonomy have remained strong taboos for China’s Communist Party. In fact, Hong Kong law professor Benny Tai Yiu-ting should have known that before speaking at a pro-independence conference in Taipei.

Taiwan sits between the East and South China Sea and, should the island host hostile forces, it would become a choking point for China, which would no longer have guaranteed access to the rest of the world.

Meanwhile Tibet, while not an island, separates China from India, which is another populous and rising nation. The Tibetan Plateau also controls a vast supply of fresh water, which flows into the Yellow, Yangtze, Indus and Mekong rivers. This is why China cannot risk Tibet becoming an independent nation. It could also lead to a military stand-off between the two giant neighbours.

Despite recent upheavals in the international arena being dominated by news of the US-China trade war and the Syrian conflict, these geopolitical theories seem to offer a decent explanation based on a rational examination of national security and survival.