Hong Kong students' poor knowledge of modern Chinese history is 'incomprehensible'

Only 10 per cent of candidates sat the exam, which is set to become a compulsory subject next year

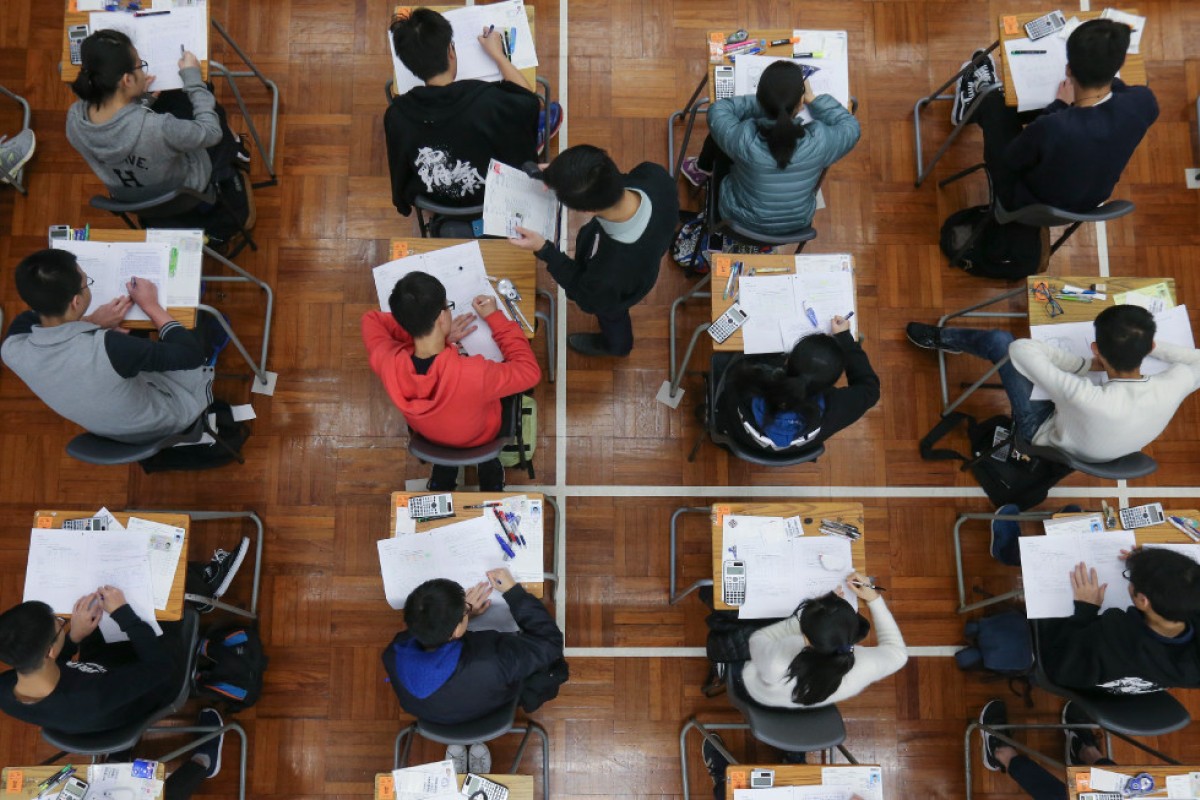

Secondary school students in Hong Kong were found to have poor knowledge of contemporary Chinese history, with some mistaking former Chinese leader Mao Zedong as a woman while others got the name of his wife wrong in the Diploma of Secondary Education examination.

The findings were part of a report on HKDSE performance released today by the Examinations and Assessment Authority.

Last week, officials announced the decision to make Chinese history an independent and compulsory subject for students from Form One to Form Three in 2018. For students from Form Four to Form Six, Chinese history has been an independent elective subject since 2009.

In April this year, 6,090 students – or about 10 per cent of all candidates – sat for the DSE Chinese history test, which includes ancient history and contemporary history. Some 89.6 per cent were graded level two or above, achieving the minimum mark for university admission.

But examiners said they found some answers by students in the compulsory part of the test to be “incomprehensible”, when candidates were asked to identify a woman depicted in a modern poem. Among the names given in answers were Mao Zedong, his right-hand man Liu Shaoqi and Lin Biao, once considered as Mao’s successor.

Although most students knew the woman in question was Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife, “a small number” of them still got her name wrong as Lin Qing or Wang Qing.

Few chose to answer questions on China’s modern history and even when they did so, markers found their answers “barely satisfactory”.

Separately, public figures such as boxer Rex Tso Sing-yu and cyclist Lee Wai-sze were repeatedly quoted among the answers given by 55,440 candidates in the Chinese language oral exam.

In a test section requiring students to analyse a story, parents were stereotyped as “monster mums and dads” and young people as “impetuous” in candidates’ answers.

“Many pupils don’t have time to focus on studying Chinese history post-1911 until they enter secondary school,” said Chan Yan-kai, deputy director of education research at the Professional Teachers’ Union.

The Education Bureau is currently conducting a public consultation on the curriculum for Chinese history, under which students aged 12 to 15 will spend more time on studying China’s affairs in the 20th century.

Chan said he believed the similar answers of students came from social media platforms instead of books and serious publications, adding that they might have attended the same tuition centres or shared notes compiled by the same tutors.