Sun Yat-sen to Mao Zedong, I watched the birth of a new China: the Wang Gungwu memoir

In an extract from his memoir ‘Home is Not Here’, one of the world’s foremost scholars on Chinese civilisation recalls visiting the country as a student – and witnessing the birth of Mao Zedong’s China

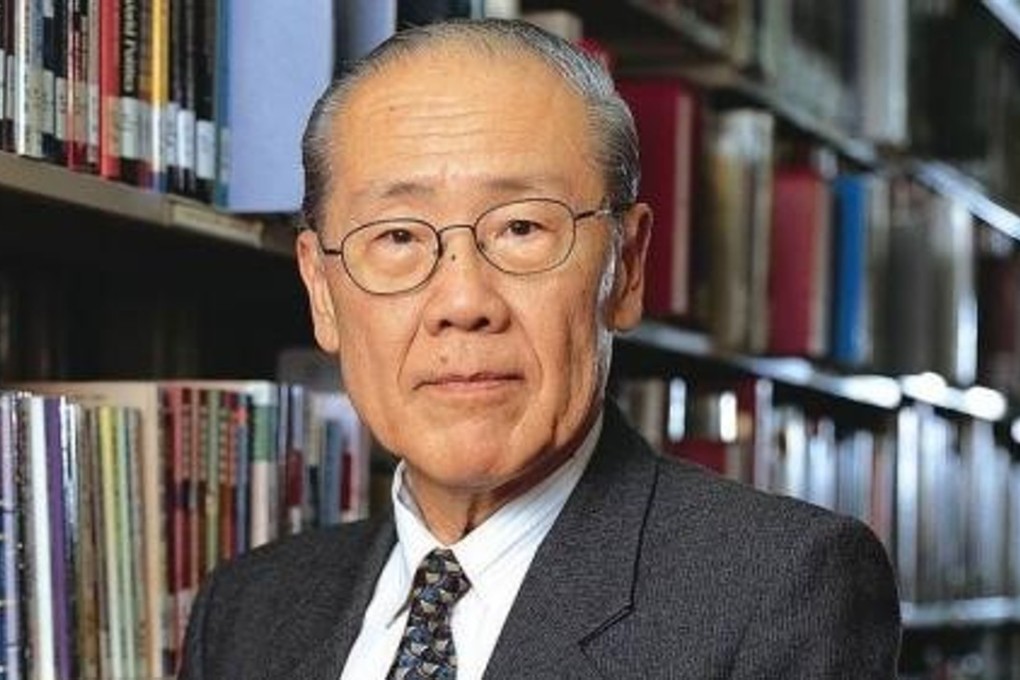

Editor’s note: Wang Gungwu is a historian well-regarded in Asia for his study of Chinese civilisation and his reflections on the Chinese diaspora. Born in 1930 in Surabaya, Indonesia to immigrant parents – a Chinese schools inspector father and a mother from a family of literati and businessmen, he lived, studied and later worked across several countries and territories, including Hong Kong where he was vice chancellor of the University of Hong Kong. ‘Home is Not Here’- is his first attempt at his own life’s history, as it traces his early years in Ipoh, Malaysia, and a brief return to China in 1947 for him to study at university, before returning back to Southeast Asia. Woven with the history of China is the arc of his own life story, trying to figure out the meaning of being a minority in one country, feeling affinity for another and making the best of the multiple identities one is forced by circumstance to embrace. He writes simply, showing a prodigious memory of vignettes from various eras, keeping faith to his true calling to honour the past because it explains so much of the present and provides lessons for the future. Here are two edited excerpts, on that brief stay in China in his youth and the beginning of the People’s Republic of China under Mao Zedong.

“When we arrived in Shanghai, my father avoided attending his cousin’s wedding party by taking me with him to Nanjing. It was only a short train journey. He called in at the High School where he had been offered a job as an English teacher. This was a school established by his alma mater, the Dongnan or Southeastern University, now the National Central University, the same one that he hoped I could get into. The university had followed the central government to Chongqing in 1937 when the Japanese forced Chiang Kai-shek to evacuate Nanjing. After eight years of refuge, it had just begun to settle back on its old campus on Chengxian Street. When we visited it, we were told that the university was now much larger and there was the medical school campus in Dingjiaqiao where the freshmen would spend their first year.

Wang Gungwu, the scholar who helped the West understand China and the ‘New Asia’

My father had me registered for the university’s entrance examinations and wanted to make sure that I understood what was required. He knew that the examination was a challenge to me because I had gone to an English school. He knew I could not do well in the science paper because I had missed many years of formal schooling, and Anderson School had offered too little on science subjects. Furthermore, I was not confident with technical terms in Chinese, having studied the subjects in English. In any case, he had me apply for the Department of Foreign Languages, where the English language would be key. He thought that, if I did well in that, all I needed was to pass the other papers. His worry was the paper in Chinese. The National Central University was renowned for its emphasis on Classical Chinese and, given the high standards required in this subject, he was not sure that I would do well enough.

Nanjing was busy with people adjusting to the new conditions after nearly eight years of Japanese rule. The organs of central government had returned from Chongqing. The economy was suffering from severe inflation and everyone was desperate to find ways to secure their livelihood. My father talked to me about the widespread regret among the people that the two major political parties could not agree to a coalition government. Everyone had hoped for peace, but the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) had marched into Central Manchuria with the support of Soviet forces, and the national government was determined to eject them. My father explained why, in early 1946 and less than a year after the end of the war, this civil war was seen as unavoidable. Despite knowing that, he had been determined to come home because he was hopeful that the national government would win. Now the fighting in northern China was fierce. It was obvious that the PLA was popular in the rural countryside and much more formidable than expected.

My father had not been to Nanjing for over 20 years. The city had changed a great deal. He was tense about the mood people were in and seemed undecided what he should talk to me about the current state of the nationalist government. Nevertheless, he had broken his silence about the politics of China.