Judging empires: Was Japanese rule in Taiwan benevolent?

While imperialism may result in some benefits for those under rule, weighing up individual cases of good and bad misses a crucial point about the structures of empire

Taiwan’s politics, even today, is shaped by the memory of the years when Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists ruled the island during the cold war. The battle between the “mainlanders” who poured in at the end of the Chinese civil war in 1949 and the indigenous Taiwanese still resonates in today’s politics.

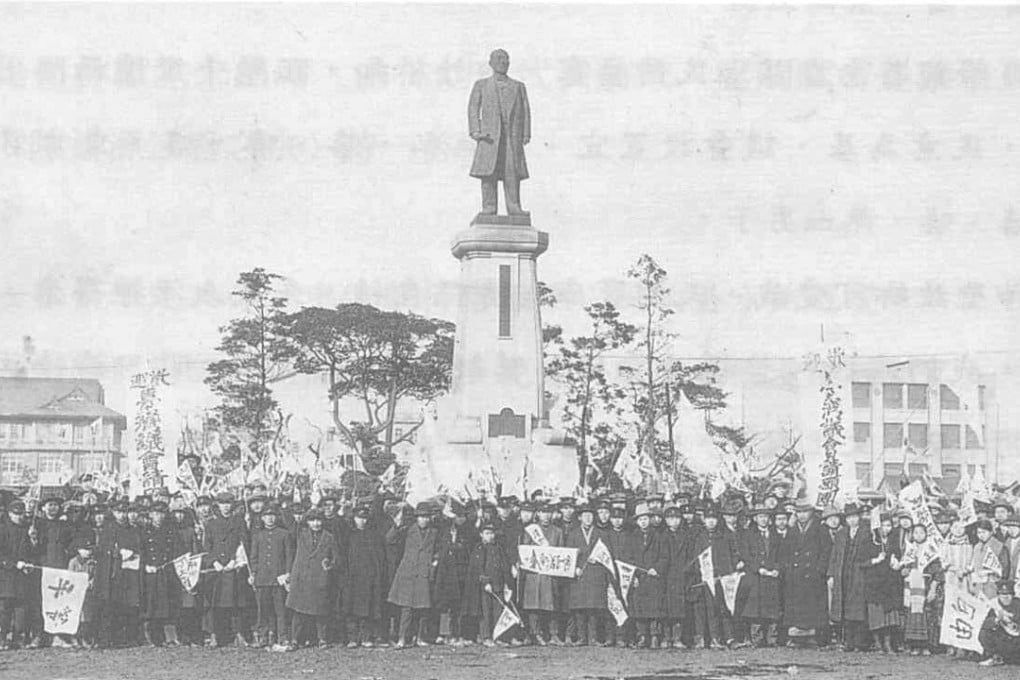

In contrast, one other relatively recent historical experience seems much less relevant: the period of Japanese colonial rule over Taiwan from 1895 to 1945. The younger generation hardly talk about those years. The older generation – and one has to be in one’s 80s or older to have any real memory of the period – often speak of the Japanese occupation with equanimity, even nostalgia.

Is Taiwan trying to erase links to mainland China, or forget a bloody past?

Former president of the Republic of China, Lee Teng-hui, who grew up in the colonial period, once famously claimed that he felt that Japanese was his first language. When they ruled Taiwan, its Japanese masters created a new Taiwan Chinese middle class which benefited from improvements in education, public health and infrastructure commissioned by their colonial rulers. Compared with the suppression of the native Taiwanese population by the Nationalists (for instance in the notorious 2.28 Incident of 1947, which led to the mass killing of many of the island’s indigenous intellectuals), Japanese rule seems quite benign.

This might seem useful material for the growing voices in recent years arguing for a more positive assessment of colonialism overall. Most of this analysis concentrates on the British Empire, rather than the Japanese or French. It argues, factually enough, that some unarguable good deeds were carried out by colonial states: for instance, the British Navy was fundamental in ending the slave trade. Overall, it argues that the best way to assess modern empires is to weigh the good and the bad and see how the balance works out.

Trump’s big button to Thai penis whitening: hail the emperor, without his clothes

Nobody fair-minded would deny that there were decent and positive actions carried out under imperial rule. But a balance-sheet approach, weighing up individual cases of good and bad, misses a crucial point about the structures of empire. These structures are always the same: they are about one set of people using power – ultimately, coercive, violent power – to control another set of people.