How Macau’s rich history shaped its fusion flavours

Macau’s unique cuisine was born of a legacy of Portuguese traders, Malay markets and kitchen alchemy

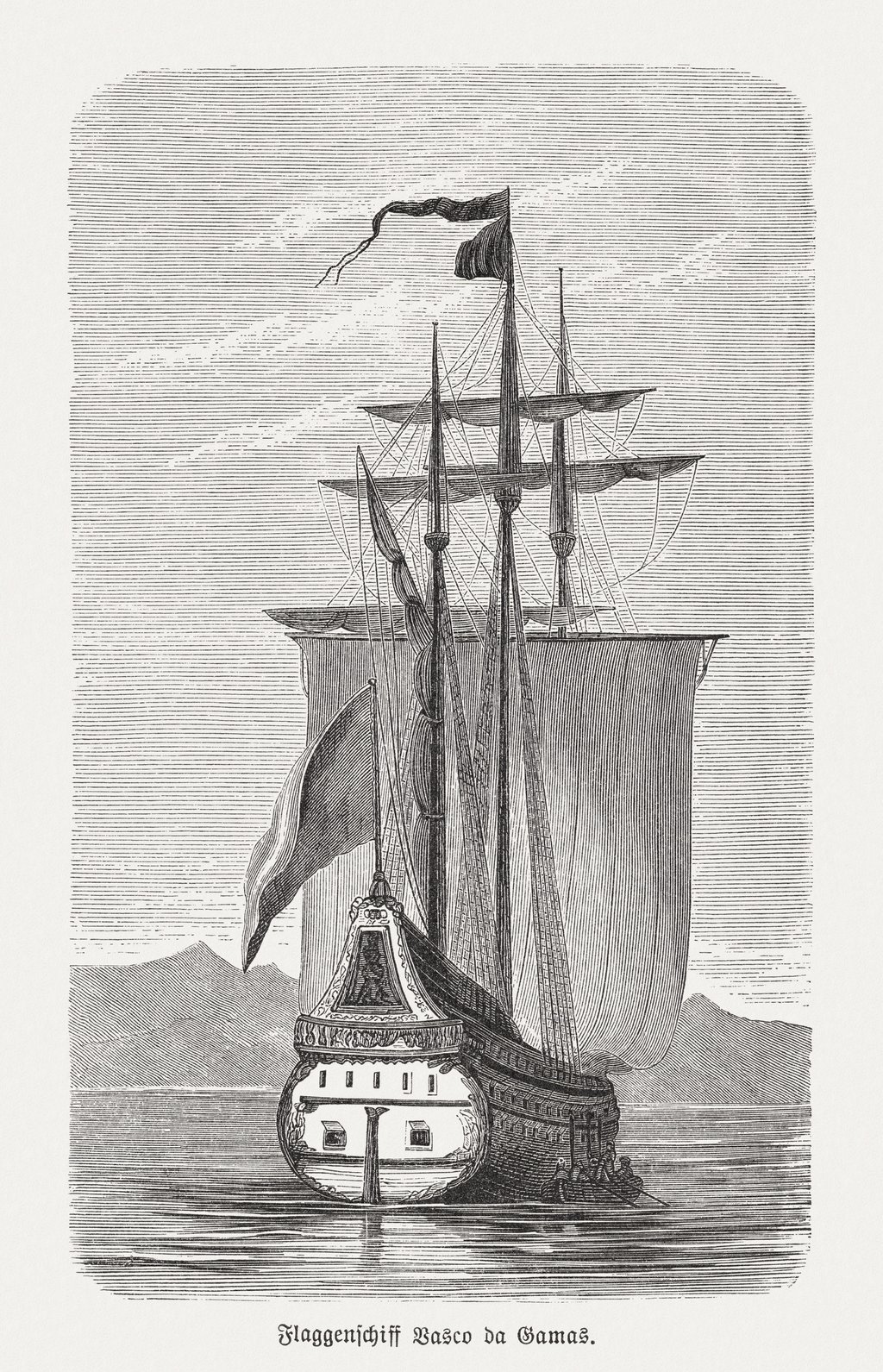

During the Age of Discovery, pepper was so sought after that “no amount of imperial prohibitions could lessen the demand in China”, according to historian John Villiers. And when Manuel I of Portugal authorised Vasco da Gama’s voyage to establish a sea route to India in 1497, the explorer set sail “in search of Christians and spices”. By 1570, Europe was importing around six million pounds of black pepper each year, in addition to large quantities of many other spices.

The city may not have been a producer of spices, but historically Macau served as a vital hub for trade, linking China, Japan, Southeast Asia and India with Europe. Its culinary scene is a living tapestry of tradition and innovation, and Macanese cuisine was officially celebrated by Unesco in 2023 as the world’s first fusion cuisine.

But this blending of flavours was never deliberate. It was born out of conquest and trade, and the simple human desire to make a foreign land taste like home. Herbs and spices didn’t just travel – they transformed, weaving new culinary identities along the way.

The spice trade’s strategic heart

Macau’s modern history begins with this trade in spices. Shortly after Portuguese traders arrived in East Asia in the 16th century they learned, according to Villiers, that there was “as great a profit in taking spices to China as in taking them to Portugal”. This was because trading in spices allowed the Portuguese to establish control over the Maritime Silk Road, an oceanic trading network stretching from the Mediterranean as far as Japan.

In their 16th century heyday, Portuguese traders would load their ships at Goa with Gujarati cottons, chintzes and other Indian textiles, as well as woollen and scarlet cloth, wine, glassware, crystal and Flemish clocks. Using the monsoon winds in April or May, they would head to Malacca where much of this cargo would be traded for Indonesian spices, camphor and sandalwood, and hides from Thailand, which was called Siam at the time.

From there the ships would go to Macau and trade these goods for Chinese silk, porcelain, musk, rouge and rhubarb. The next stop was Japan, where the newly acquired Chinese merchandise would be sold for Japanese silver, gold, copper, lacquer, painted screens, swords and other weapons, and slaves.

In November, the Portuguese would head back to Macau where the silver acquired in Japan would be exchanged for gold, copper, ivory, pearls and more Chinese silk. From Macau, the ships would return to Goa and then onwards to Europe. But these trade routes shipped more than just bullion and spices – they transported new ideas, traditions and flavours that would forever reshape Macau’s identity.

By the 17th century, the increasing prominence of Dutch and British merchants in Asia began to change global trade, yet Macau remained a linchpin of East-West exchange. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the city became the primary hub for China’s tea exports – proof of its enduring influence.

A living legacy

Today, Macanese cuisine is a vibrant testament to centuries of cultural exchange. Rooted in Portuguese traditions, it has absorbed flavours from Africa, India, Southeast Asia and southern China.

In Macau, mixed marriages blurred cultural lines and kitchens became laboratories for experimentation. Women – often the unsung architects of this cuisine – melded inherited recipes with new-found ingredients traded there, crafting dishes that spoke of distant homelands and new beginnings. For generations, Macanese recipes survived not in cookbooks, but in memory. Guarded like heirlooms, they were passed down the generations in kitchens, their secrets kept close.

“For us, Macanese food is fundamentally family food – comfort food,” says Filipe Ferreira of Michelin-recognised Restaurante Litoral Taipa. “Some cuisines thrive on innovation, but ours is about preserving tradition. That’s what makes it special.”

When Portuguese ingredients were scarce, local Chinese staples filled the gap: soy sauce replaced salt, peanut oil stood in for olive oil, and the vibrant flavours of Guangdong transformed dishes into something entirely new.

The influence of Goa and Malacca also runs deep. In the 16th century, Malacca’s bustling spice market was the epicentre of global trade, where Indian and Malay peppers fuelled culinary revolutions. Some spices were luxuries, too costly for most. Enter the South American chilli: cheap, hardy and flavourful. Adopted by Malay women and carried to Macau by traders, it became indispensable. From the Indian subcontinent came turmeric, cumin and coriander, spices that melded with Portuguese techniques to create Macau’s distinctive curries.

Even the British left their mark on Macanese cuisine in unexpected ways. Minchi, now one of Macau’s signature dishes, is said to be born from the English word “mince”. This hearty stir-fry of ground meat, potatoes and onions often swaps traditional molasses for Worcestershire sauce, a testament to colonial ingredient innovation.

Honouring the past, embracing the future

Macau’s chefs stand as steadfast keepers of history. As they honour tradition while embracing innovation, the city’s food scene bridges past and present. From the spice routes of the 16th century to its modern status as a Unesco Creative City of Gastronomy, Macau’s flavours have always evolved and always captivated.

The secret lies not in rigid preservation, but in adaptation, with every generation adding a chapter to an ongoing, delicious history. As Macau Government Tourism Office director Maria Helena de Senna Fernandes notes, the use of spices and herbs from East and West has “shaped a unique cuisine and is part of the essence of Macau’s food culture”.