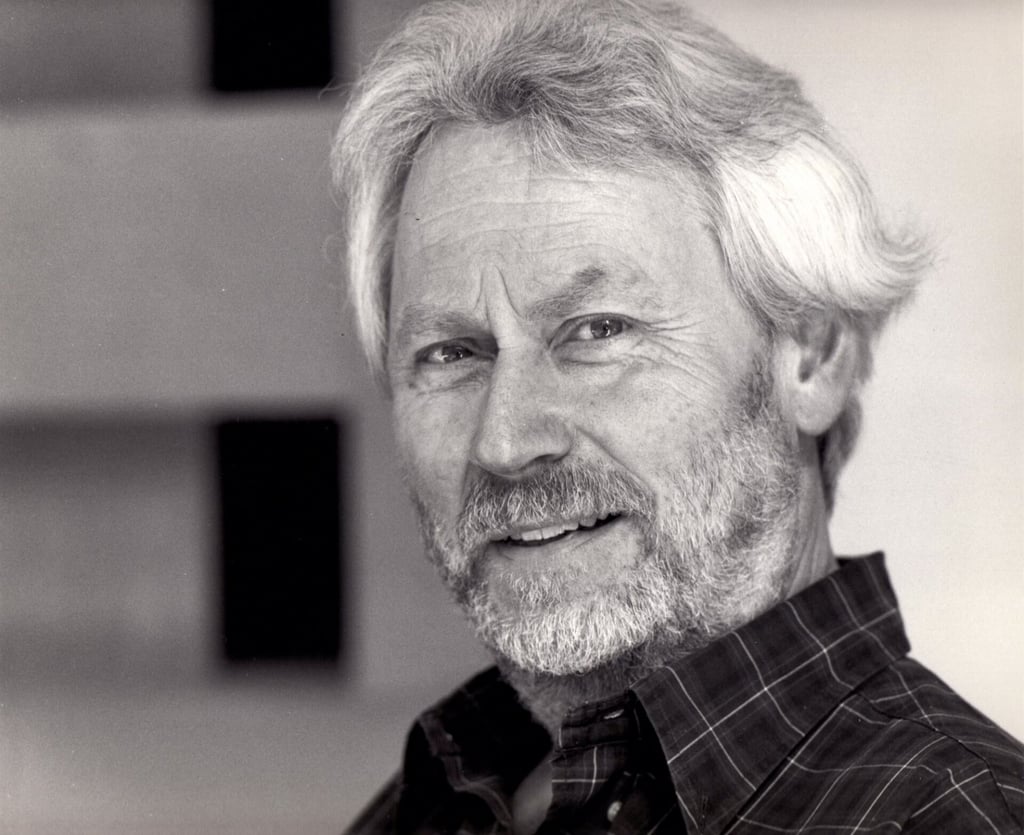

How American minimalist Donald Judd sought to simplify the complex in his stark designs

The US artist and designer believed his works should be ‘the simplest expression of complex thought’, allowing viewers to enjoy them in their purest form

Any creative act can be judged by the extent to which the essential is identified and the extraneous eliminated: think of Michelangelo famously “extracting” his David from a block of stone. The best attain this purity without any apparent exertion. Like tai chi grandmas synchronised at dawn or Taoism’s wu wei doctrine of “effortless action”, Donald Judd’s art and design, as new book Donald Judd Furniture underscores, embodies what he described as “the simplest expression of complex thought”.

Judd is known for his boxlike works, that he called “Specific Objects”, made from “anti-art” industrial materials such as plywood, aluminium, coloured Perspex or folded sheet metal. Always scaled for their intended context, they sometimes sit on the floor (never on a pretentious plinth), if they’re not stacked or wall-mounted. Or they repeat. Judd was preoccupied with what the Japanese call ma: the interval, pause, rhythm or the negative space between things and how objects interact with the viewer and each other.

Judd hated to be categorised as a minimalist, arguing the description was too broad to define his art, and refused to call his work sculpture because it wasn’t sculpted but fabricated in workshops and factories. He aimed to “eliminate the hand”. Judd wanted the viewer of his works to be in the now, to experience the essence of the object without any art historical baggage: the viewer’s contemplation of the art shouldn’t be shaped by any perceived act of form giving.

Judd believed that, despite the challenge of making these seemingly simple, “perfect” forms, the physical act wasn’t terribly interesting and the involvement of the artist (“the hand”) should be essentially invisible. But in reality his works eliminated evidence of the hand, rather than actually eliminating the hand – the execution was too precise to expect a machine to get it right without meticulous hand-finishing and polishing. As Judd wrote in his seminal 1965 essay “Specific Objects”, “Nothing made is completely objective, purely practical or merely present”.

His homes were an eclectic paradise of wu wei and ma. Judd was a lifelong collector and surrounded himself with good design. Much of it was beautiful and unpretentious – handmade rag rugs from his home state (and mine) Missouri; Native American and Mexican crafts; pottery; Shaker woodwork – interacting with rarefied pieces of furniture, including chairs by Michael Thonet, Mies van der Rohe, Alvar Aalto, Rudolph Schindler and Gerrit Rietveld. He knew his stuff.

In 1970 he started fabricating furniture, responding to family needs and to complement the furniture he already had. He despised most of what was available in stores: stuff he considered to be bourgeois, decorative junk. Initially he made a series of simple timber beds, then chairs, then plywood versions, later sheet metal and welded steel pieces. These pieces show a clear patrimony: spare, essential forms explicitly related to his art but that were not, he insisted, art – they were designed to be furniture used as furniture.

In his 1993 essay, “It’s Hard to Find a Good Lamp”, included in the new book, he wrote, “The art of a chair is not its resemblance to art, but is partly its reasonableness, usefulness, and scale as a chair”. And further: “Of course if a person is at once making art and building furniture and architecture there will be similarities. The various interests in form will be consistent. If you like simple forms in art you will not make complicated ones in architecture.”