From refugee to music entrepreneur in the wake of war

Fifty years after the end of the Vietnam War, refugee-turned-vinyl entrepreneur Paul Au shares how music changed his life

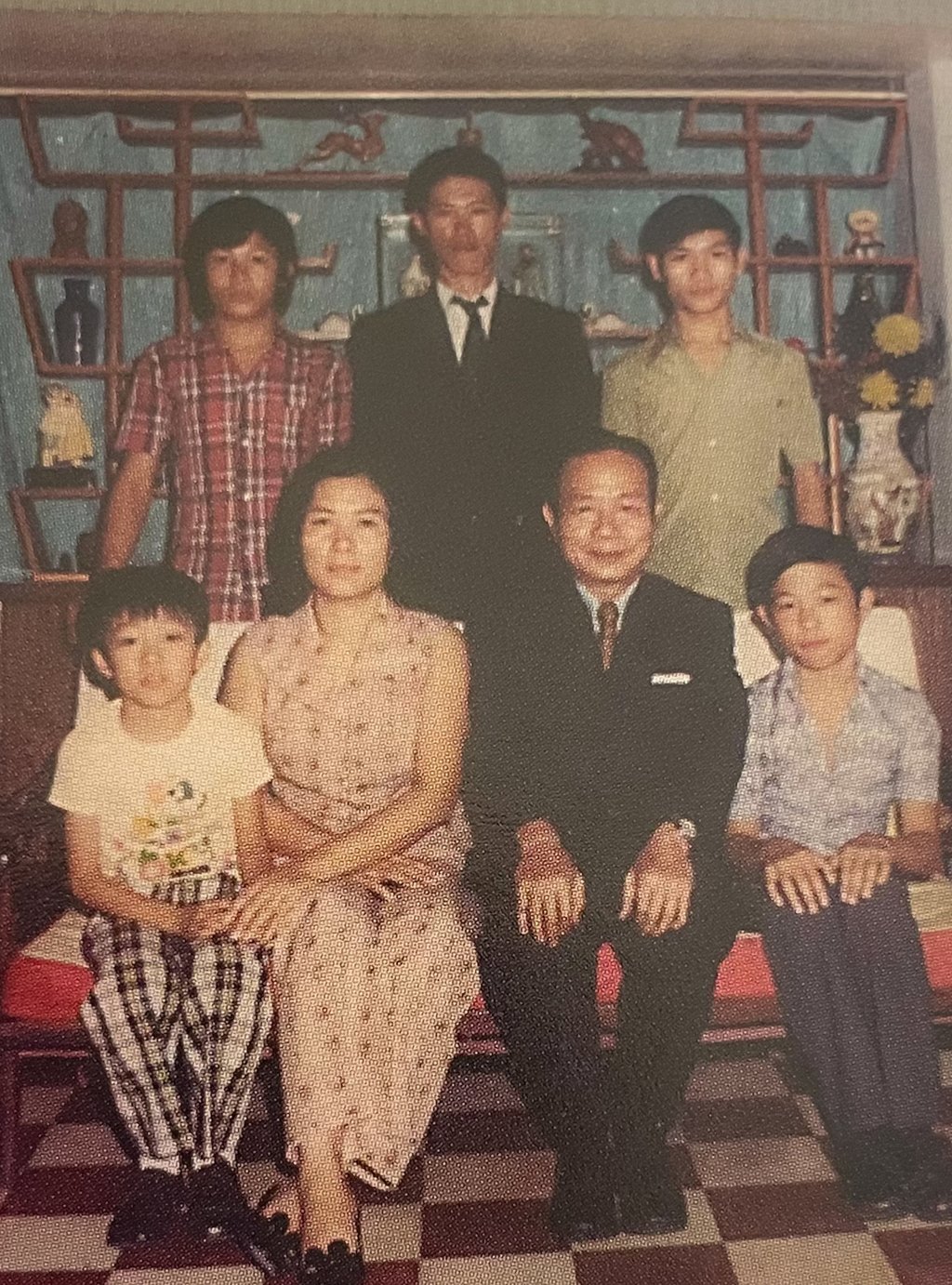

I was born Duc Thanh in Saigon in 1957, a baby boomer! My father worked in a hotel. He was educated by the French but sent me to a Chinese kindergarten. My mother was from China but grew up in Hong Kong and Macau, and she told my father, “Hey, send our babies to learn English, because they might go back to Hong Kong or Macau or go to the West.” So, me and my three younger brothers went to the English institute.

Vinyl in Vietnam

Choppers and bell bottoms

Time to go

At night we could see the sky going red across the river, people were being killed. The big boys next door were drafted and they never came back. A lot of them, they never came back. My parents were very worried because it wouldn’t be long before I had to go. If you could pass a Vietnamese language exam for the elite you didn’t have to go, but I couldn’t speak Vietnamese. So, finally, in late 1974, after my 17th birthday, I escaped to Hong Kong. We had to wait in a house for several weeks and then got on a big cargo ship. I think it was from Taiwan. Altogether there were 250 Chinese-Vietnamese people on board, including grandmas. I went with my cousin. I was not scared because it felt like an adventure. It was four days and so boring – just sea and no land. My parents had paid gold to a middleman. I had very little money. Later one of my younger brothers escaped. He went to Thailand. Now one lives in the United States and the other in Toronto, Canada. One went missing when he escaped. We never found him.

Chinese New Year at Shek O

On Chinese New Year’s Eve in 1975, we were outside Hong Kong waters, waiting for local fishing boats to fetch us. But we were told that first they had to rest and celebrate the New Year. So we had to wait four more days. Then they transferred us at about 8pm. I jumped down onto the beach and squatted in some grassland. Later I found out it was Shek O. It was then that I saw my first double-decker bus. I had only seen them in the movies. I telegrammed my parents to say I’d arrived. My grandmother and my uncles had a rooftop wooden house, a squatter hut on top of a tong lau in North Point. From North Point I went on to live in another rooftop house in Sham Shui Po, in 1983.

Urban cowboy

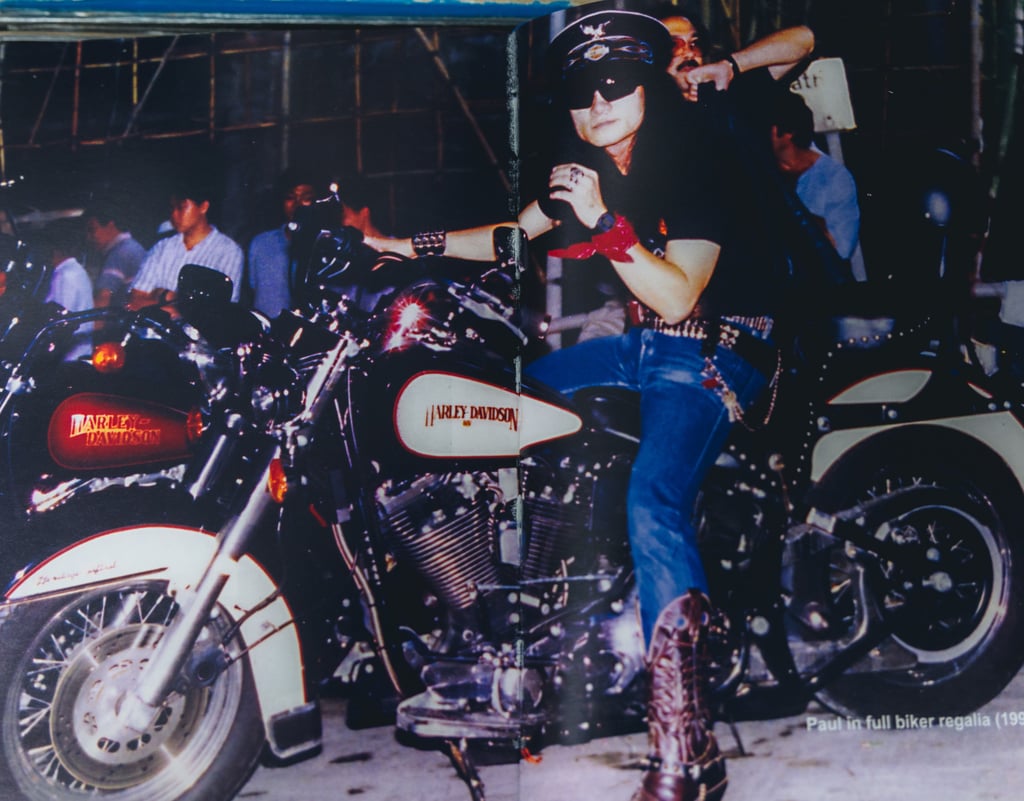

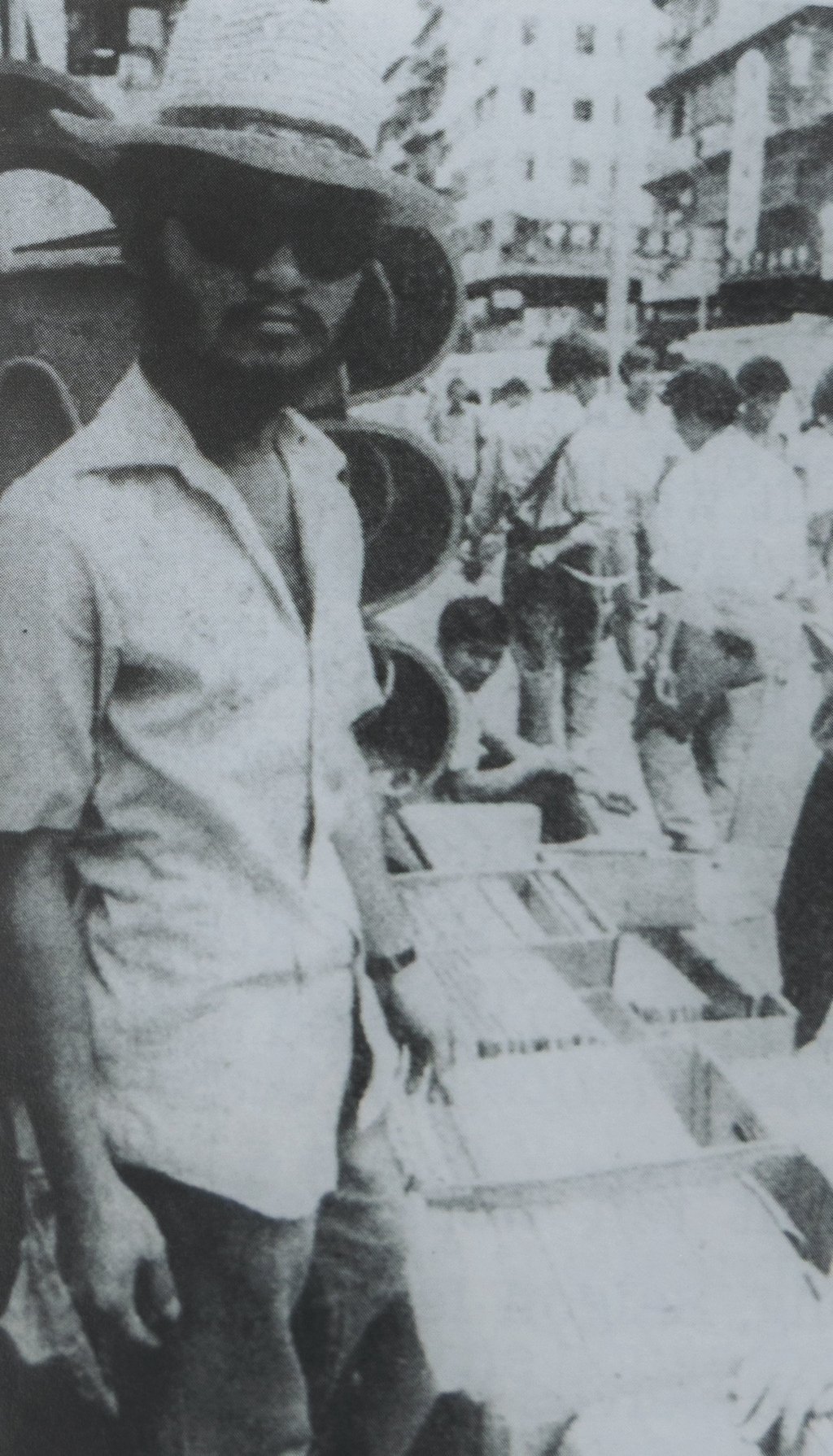

I did odd jobs on the street and started collecting records that I would sell. In Sham Shui Po, I was next to a flea market. I had many favourite records from the 1960s and 70s and some were doubles, so I started to sell them on the streets. Then I started getting more and more records. There were too many and they were too bulky, so I slept on the street to watch my records day and night, just like the cowboys watching their cattle in the West, like a modern-day cowboy. The Urban Council would come and clear the streets, so my records were unsafe. I started with one trolley, then a second, a third, then finally a train of trolleys all on the street. I covered them in plastic sheets and, when the Urban Council came, I would move them around. During that time I also bought a Harley-Davidson motorbike. I had it for 15 years, but in the end I sold it to pay for more storage for my records.

Qipaos and Percy Faith

Why do I love vinyl so much? Because I never grew up. I’m still living in the 70s and 80s. You cannot see time, but when you listen to the songs, you are back there. I love them so much. I’m still the same crazy boy who never grows up. Let me put this record on, it doesn’t cost much in Hong Kong still – “Lover’s Tears”, sung by Poon Sow Keng. It is so sad and melancholy. It’s in the (1965) movie The Lark, with (composer) Joseph Koo’s sister (Carrie Ku Mei) acting. It made her famous. I saw it with my mother in a cinema in Saigon and everyone was crying. My mum used to dress like that, in a qipao. I also love Percy Faith’s “Theme from ‘A Summer Place’”. That’s probably my all-time favourite.

Vinyl hero

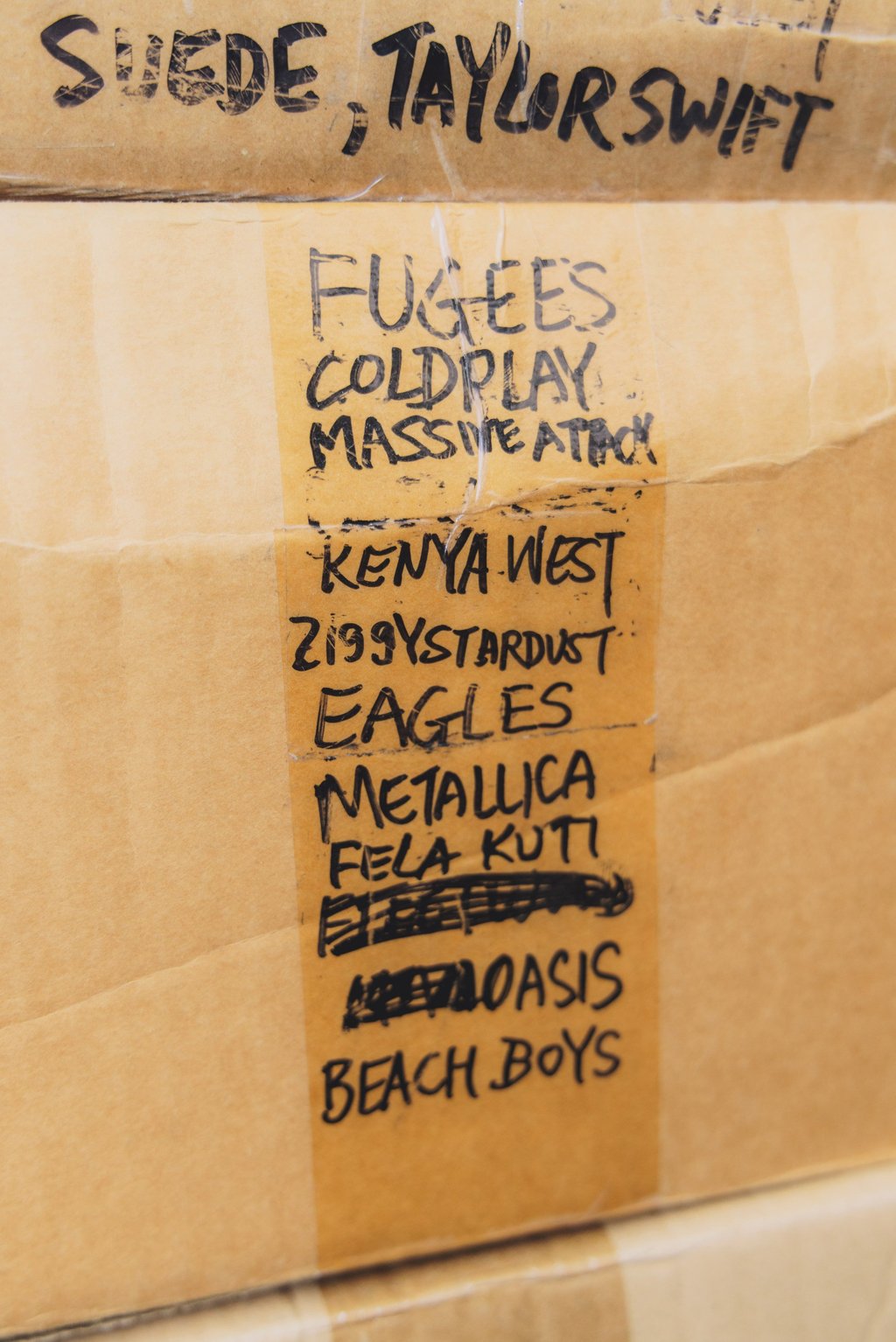

I have about 30,000 records here and the rest in a warehouse. How do I know where records are? I have a GPS inside my head. So, it’s just like I’m Tarzan of the jungle, because, if you go into the jungle, there will be no GPS; you cannot locate the tigers and the monkeys and whatever. But Tarzan, he knows everything.

Journey back in time

Some grandfathers come in here and they want to go back in time. Young Korean tourists also come in to buy records. In 2015, I did my book (Paul’s Records, by Andrew Guthrie). I have never been back to Vietnam. I was very worried after the fall of Saigon but in 1983 my parents left for Canada and I have visited them there. I dream of going back to the house where I grew up. A Korean friend went there and took a video, and it’s just the same! The blue door is still there, and the balcony where when we were small we could just look through the gaps. I dream that I will bring my book and I will knock on the door. If the people come out, I’ll say, “Fifty years ago, I lived in this house and this book is me.” And I’ll ask them if I can take my (vinyl) Walkman and listen to music in their house from that time.

Paul’s Records: How a Refugee from the Vietnam War Found Success Selling Vinyl on the Streets of Hong Kong (2015), by Andrew Guthrie, Blacksmith Books

Vinyl Hero, Flat D, 5/F, Wai Hong Building, 239 Cheung Sha Wan Road, Sham Shui Po, Kowloon