He escaped death by beheading in 1940s Hong Kong, then became a British oil exec

Now 98 years old, Hui Yin-kan survived the Japanese occupation during World War 2

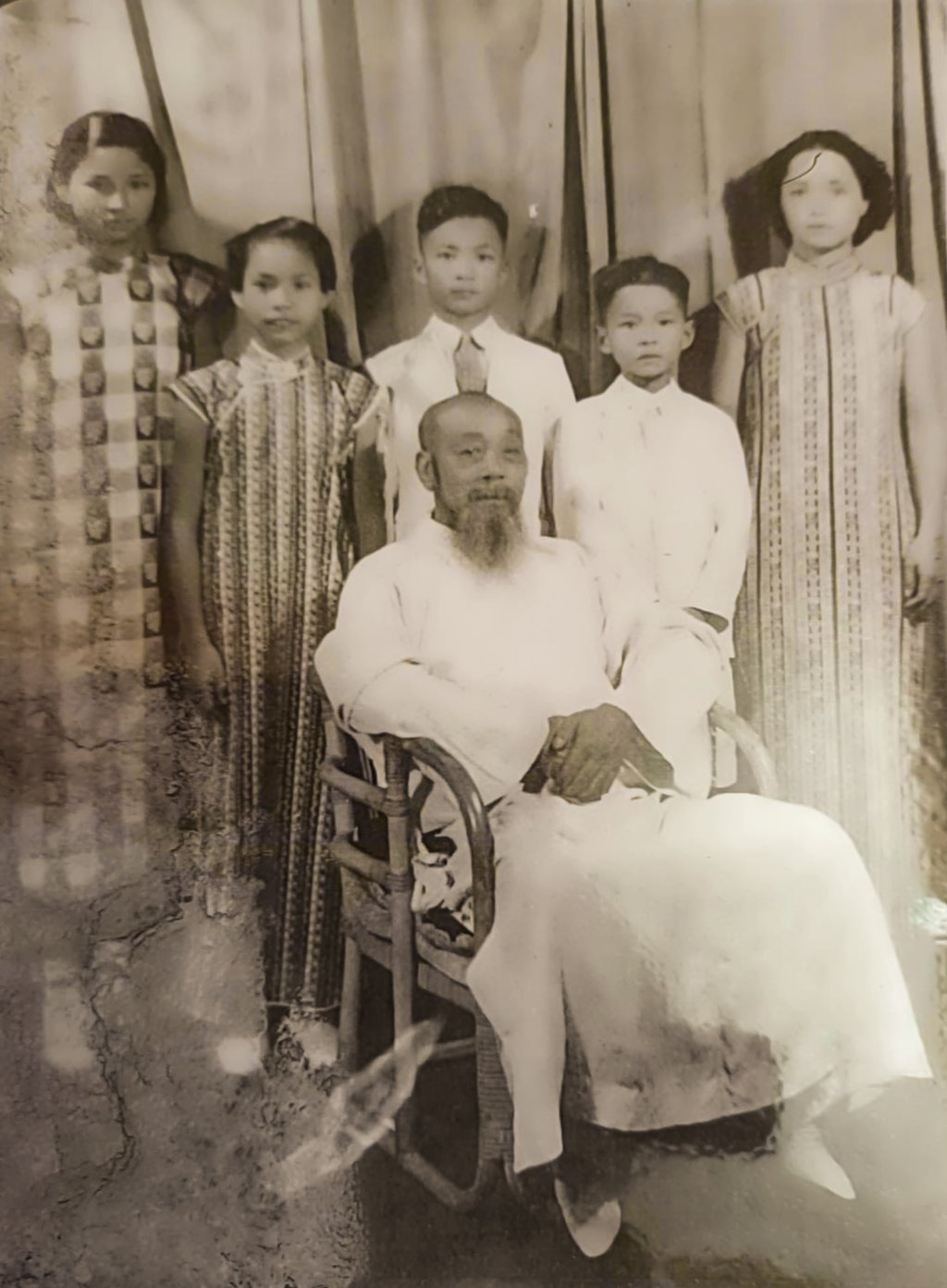

In the early 1900s, my grandfather was a trader operating between Hong Kong and Foshan, in Guangdong. His eldest son was my father, Hui Lap-sam, who helped him in the business. My dad’s two brothers were a decade younger than him and lived in Foshan. On one occasion, as my dad and grandfather were entering the Foshan city gates, my dad was relieved of all his money so that my grandfather could enjoy the opium.

Big brother

It wasn’t long after that that my father’s younger brothers moved to Hong Kong. The three brothers lived together in Kowloon City and founded China Brothers Hat Manufacturing Co, which went on to become one of the largest hat manufacturers in Hong Kong and China. By 1934, the firm was doing more than HK$1 million in sales and employed more than 500 workers.

Early grave

My mother was my father’s second wife. I was born in 1926 and was one of 12 children and the eldest son. We lived in a house in Kowloon City, not far from the hat factory. When I was five, my mother died from a brain tumour. I was at her bedside when she passed away. I asked my father why everyone was crying but he wasn’t, and he burst into tears. Her funeral procession ran all the way from Diocesan Boys’ School in Mong Kok to Kowloon City.

Kung fu and opium

When I was seven, I was sent to a kung fu school in Yau Ma Tei and learned the 108 wing chun movements, the same martial arts style that Bruce Lee later made famous. I went to Diocesan Boys’ School (DBS). My father was the vice-president of the Chinese Manufacturers Union. As a child, I often accompanied him to meetings in restaurants. In those days, it was common for rich people to smoke opium. I would practise my kung fu moves on the opium bed.

Under the Japanese occupation

In December 1941, the Japanese occupied Hong Kong. The hat factory suspended production. The city changed very quickly. Initially, the Japanese said one yen was equivalent to HK$2. A couple of months later, they said it was equal to HK$4. And then the Hong Kong dollar was outlawed and replaced with the Japanese military yen. Anyone who was found carrying money other than the Japanese money would be taken away and executed and their body kicked into a hole in the ground.

Power of persuasion

My schooling ended abruptly with the war. Many DBS students aged 17 or over joined the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps. They all died. I began working with my dad, helping him run the hat factory. The Japanese confined at least 20 of our factory workers to their houses near the factory (the first step towards confiscation for occupation by the Japanese). I went to see the head of the occupying forces to persuade him to let them out. He was based in the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, which the Japanese were using as their military headquarters. I had to pass a long row of gendarmes, but I wasn’t afraid because I was loyal to my father. I convinced him that the houses in question were unsuitable for the Japanese, and that he should instead look at using houses that were already deserted by the occupants and had gardens in which the soldiers could practise their killing skills. They routinely performed executions, beheading people, and they practised on animals. Fortunately, I never saw anyone killed this way.

He agreed with my request.

Dicing with death

There were 20 times during the war when I narrowly missed death. I swallowed my fear. I was quite willing to die. It was a very difficult time. The Japanese put up checkpoints all over the city and would stop and search you. One day, I was unexpectedly stopped at a checkpoint. I had some money hidden in my left sock. They asked me to take off my shoes. My heart was beating fast. Luckily, they didn’t see the notes pressed against the sole of my foot. I put my shoe back on feeling very relieved – it was a narrow escape. I had to be smart and think on my feet. I made myself an armband with the words “Powerful, permission to travel”. If the Japanese soldiers had looked at it closely, they’d have seen it was a fake, but fortunately they didn’t.

From the dark side

Our money was in safety deposit boxes in the Bank of East Asia on Hong Kong Island. That meant crossing the harbour to get there, which the Japanese had declared illegal. From our home, the closest access to the harbour was Hung Hom. My father and I climbed a couple of fences and reached the waterfront. We managed to fend off two bandits who tried to rob us and paid a sampan driver to cross the harbour. The return journey was just as tough. The Japanese gave out 100 permits a day for people to travel to Kowloon. I got up very early to get one but missed out. I rather craftily rolled up a piece of paper and offered it to the person checking permits. He was in a hurry and didn’t look closely and I got away with it. It was another close call.

Fateful day

There was a suggestion that the hat factory would be made to work for the Japanese. My father was resolutely opposed to this, and he stuck to this position all through the war. In 1944, he was on a passenger steamer called the Lingnan Maru travelling to Macau. The boat was sunk by Allied bombers and he was killed. After his death, one of his brothers, under the influence of his powerful wife, agreed to turn the family factory to work for the Japanese. After the war, that brother continued running the factory. He gained immense wealth from it.

A Cockney kid

My first love was music and my second love was football. In 1948, I went to Hong Kong University to study chemistry. I was captain of the football team through my university years. In my second year at university, I met Vera Lo (granddaughter of Sir Robert Hotung). She had a big car, a Hudson, and offered to ferry me, my team and our equipment to matches. Vera drove the car. It was a good time. Vera was learning singing and I accompanied her on the piano. We got married in 1951 and moved to London, where I completed my studies at the London Polytechnic. We lived in North Finchley and it was there that our first son, Geoffrey, was born. He was a Cockney.

Life of a salesman

I graduated in 1958 and wanted to know how the very big corporations were run, so I went looking for a job in a big company. I approached Shell and applied for a job as a salesman. I was offered a job as an executive. This was almost unheard of at the time – until then, executives were always British. After two years, I was given a management position. We had three more children, all boys – Edmond and the twins, Philip and Daniel. During my career, I moved back and forth between the UK and Hong Kong.

Fifty years of retirement

I was in the senior management team, the deputy sales manager, when I retired from the Asiatic Petroleum Company (a joint venture between Shell and Royal Dutch) in 1975. I felt I’d already lived a very full life and had no idea that I would live this long. I recently celebrated my 98th birthday. I kept myself busy after I retired serving as a director for several small firms. We have four grandchildren. I live with Vera in our flat on Conduit Road, in Mid-Levels. I have so many stories in my head from those war years. I can remember those days very clearly.