Meet the little-known ‘collector of anecdotes’ who wrote about underexplored Hong Kong history, culture and society

Until recently, writing about local history was the sole preserve of hobbyists whose work went largely unrewarded – just look at Lo Kam

Relative obscurity in one language group, and near-universal name recognition in another, has always been a hallmark of writing on Hong Kong. From the colony’s mid-19th century urban beginnings, local-studies enthusiasts of various stripes have typically worked in parallel obliviousness, with little crossover between Chinese-language and English-language research output. Exceptions exist; Lo Hsiang-lin and his pioneering Hong Kong and Western Cultures (1963) remain a rare early example of a successful readership crossover. Nevertheless, these outliers confirm the general rule of mutual exclusivity.

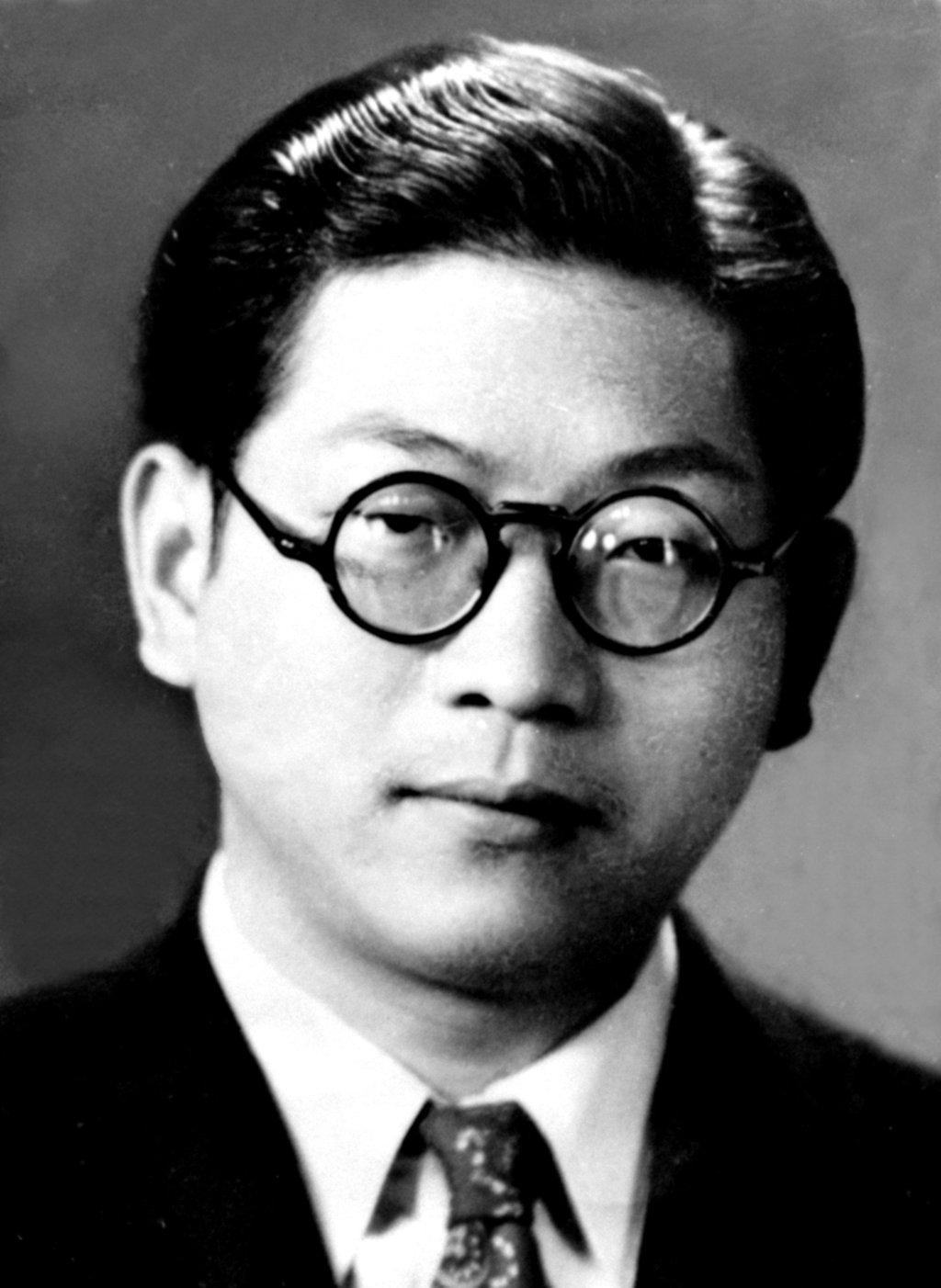

This local conundrum is best epitomised by veteran journalist Leung Tol (1924-1995). Known across Chinese-literate Hong Kong by his nom de plume Lo Kam, Leung wrote prolifically for decades on a vast array of topics. While still widely remembered by the general public, Lo Kam nevertheless remains almost completely unknown outside Chinese-literate circles.

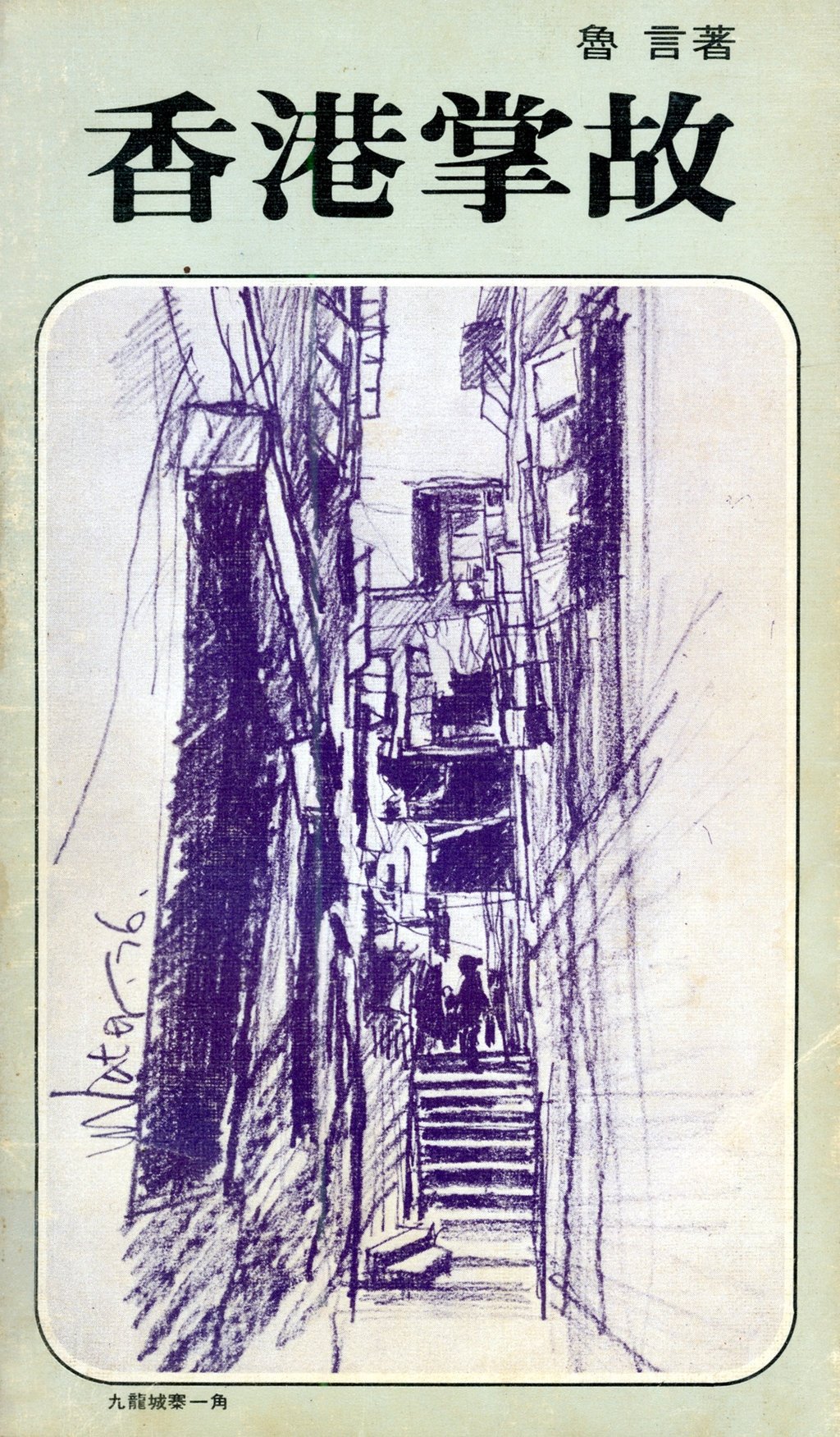

Often described as a “collector of anecdotes”, Lo Kam wrote quirky newspaper columns in popular Chinese-language newspapers that covered what were then little-explored aspects of Hong Kong history, culture and society. Lo Kam’s interests were wide-ranging; one article could explore an otherwise long-forgotten shop on a Kowloon backstreet, along with precise details about who owned it, where they originated, what the business sold, why it was locally famous for a period, who were the principal clientele, why the business eventually closed down, and what people living in the vicinity still remember about what had once seemed a permanent local institution. In half a page, Lo was able to accurately recreate a vanished fragment of earlier times and places.

Other local-interest columnists came and went, but to Chinese-language readers Lo Kam remained the gold standard against whom all others were judged. Through such popular historical writing – typically regarded by “serious” scholars and researchers to be of little value – he piqued the curiosity of two generations of Hong Kong people in aspects of their own history, culture and society that may not have otherwise interested them.

Until well into the 1990s, local history was considered a quirky minority interest, which attracted cohorts of amateur enthusiasts with widely variable research abilities. While formal academia steadily developed a more professional study of Hong Kong through the work of pioneering academic historians at various tertiary institutions, general public interest lagged behind. Topics that had been the near-exclusive preserve of hobbyists in the 90s had become mainstream academic research and publication activity by the late 2010s, and output continues to grow.

Quiet dedication to local history popularisation tends to go unthanked and unrewarded, and offers no pathway to personal wealth – especially in Hong Kong – or indeed anything like a secure income or future pension plan. Described by one long-term friend as an “old-style writer/journalist who was dedicated to what he was doing, Lo Kam wrote to the very end of his life, which was quite sudden as he was not that old. And he needed to struggle most of his life for a living.” But nevertheless, such enthusiasts did what they did because they found their work meaningful, and so continued to labour quietly, with little recognition and less financial reward. And in consequence, Hong Kong is intellectually a far richer place than it might have been.

Thanks to timely action after his death, Lo Kam’s collections were saved, along with extensive files of his published and unpublished work. This valuable archive of books and periodicals related to Hong Kong, Macau and Canton can be consulted by the general public at the Hong Kong Central Library – an enduring legacy for future generations of Hong Kong enthusiasts.