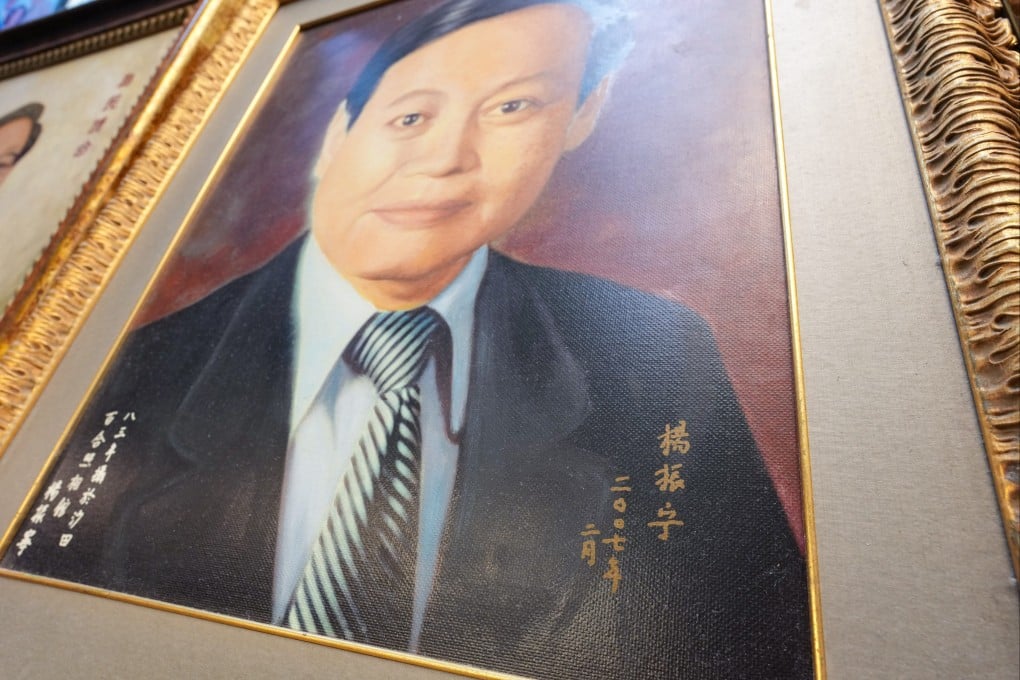

Editorial | Great minds like Chen-ning Yang lit the way for China’s tech progress

The Nobel Prize-winning physicist helped strengthen scientific education in China and inspired political and scientific leaders to aim for breakthroughs

That towering achievement, the result of Chinese-born Yang’s work with American physicist Robert Mills in the 1950s, would have been plenty for a stellar career in physics. But later that decade, he and Shanghai-born Tsung-dao Lee won the Nobel Prize in physics – a first for Chinese-born scientists – for their foundational discovery of what is called broken symmetry, also known as parity non-conservation in weak interactions. The assumption among physicists at the time was that when a particle decayed, it would always result in the same number of subparticles. The pair suggested that the number of subparticles so created could vary, and experiments later verified it.

Yang’s lifework was dedicated to the universal advancement of human knowledge. But his own lifelong passion was a commitment to building scientific education in China, and facilitating exchanges between the country of his birth and the United States where he did his most important work.

Yang took advantage of the thaw in the relationship between the two countries from the early 1970s to promote exchange and education programmes. He also helped establish several leading research institutes on the mainland and was a founding council member of the prestigious Shaw Prize in the sciences in Hong Kong.

Yang would have been saddened by the increasingly bitter rivalry between the two superpowers and the gradual decoupling in their scientific and technological endeavours today. We can only hope the spirit of friendship so fruitfully demonstrated in the epoch-defining collaboration between him and Mills will be revived in future.