Is China’s top-down science strategy driving innovation or killing it?

Study challenging view that free exploration is best for innovation sparks debate over role of state-driven science in frontier research

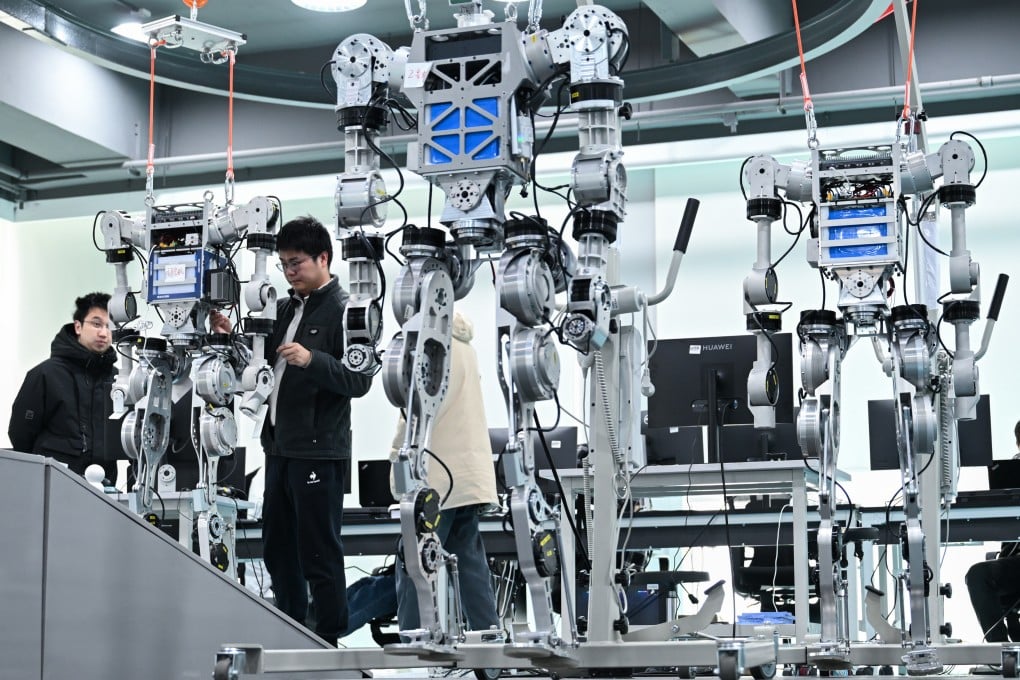

A large-scale empirical study by the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (UCAS) has challenged entrenched assumptions, showing that in China’s recent surge of scientific breakthroughs, organised, state-driven research has proven far more impactful than curiosity-driven exploration.

The analysis of more than 87,000 papers published by 185 national key laboratories found that projects aligned with national strategic goals – backed by interdisciplinary collaboration, resource concentration, and mission-oriented teams – were significantly more likely to yield high-impact breakthroughs.

Projects born of free exploration – despite its celebrated role in fostering serendipitous discoveries – showed no statistically meaningful correlation with major advances within large-scale teams, according to UCAS. The divergence, the study argues, stems from systemic advantages: centralised frameworks efficiently mobilise talent, funding and infrastructure to tackle complex challenges, as exemplified by China’s lunar probes, quantum satellites and infrastructure megaprojects.

As nations grapple with balancing agility and scale in innovation policy, China’s hybrid model – harnessing top-down coordination while cautiously nurturing exploratory niches – offers a provocative template for the era of “big science”.

The survey of data from state key laboratories included 108 labs affiliated with universities and research institutes, and 77 affiliated with enterprises. National labs are a critical force in China’s scientific research landscape.