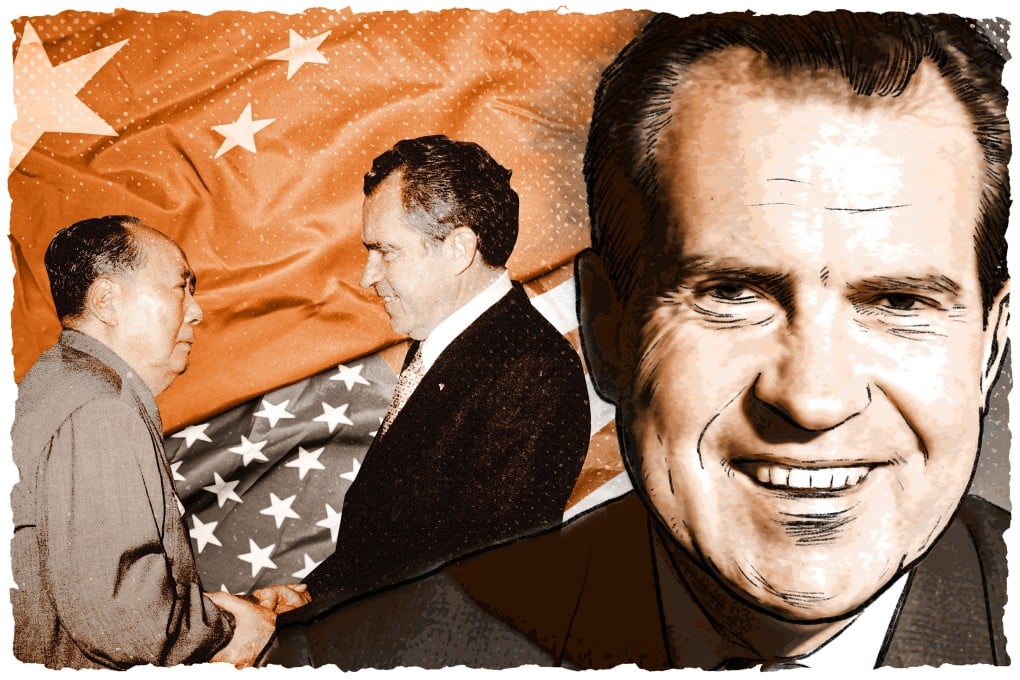

When Nixon met Mao: 50 years later, reverberations are still felt

- A hinge point in modern history, the US president’s trip to China outflanked the USSR and helped bring Beijing out of international isolation

- A key was the Shanghai Communique, ‘a very peculiar document’ which acknowledged what the two nations did not agree on

In the modern history of international relations, few moves held more consequence for the global balance of great powers than US president Richard Nixon’s visit to China 50 years ago this month.

The trip that set Washington’s course towards formal diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China was based on a novel geopolitical calculus that defied American hawks and doves alike. For China, Mao Zedong’s handshake with Nixon in Zhongnanhai, the leadership’s compound next to the Forbidden City, ran counter to decades of his own propaganda.

“It will be a safer world and a better world if we have a strong, healthy United States, Europe, Soviet Union, China, Japan, each balancing the other,” Nixon said in a Time magazine interview, discussing his trip just weeks ahead of it.

The comment signalled a departure from a concept that dominated American foreign policy for decades – the domino theory, which posited that the establishment of communism in any one country would lead to the same outcome in others. Acting on this theory, Washington concluded a raft of treaties including the Anzus Pact with New Zealand and Australia in 1951 and the US-Japan Security Treaty a year later.

Adherents to the policy saw communism marching south from the Soviet Union to China, and Vietnam appeared next to succumb. This led America into the civil war in the Southeast Asian country, a growing conflagration that was so unpopular in the US, it gave Nixon cover to change the script.

Many felt the Chinese were even more extreme than the Soviets. The Chinese side – it was sensitive for them as well.

In the midst of domestic social upheaval and desperate to find a way out of the conflict that would avoid the “domino effect” that would banish US influence from Asia, Nixon knew that diplomatic relations with mainland China might provide a measure of insurance.