Unsettling dance, The Great Tamer, to take Hong Kong audiences on mythical journey into heart of darkness

- Greek director and choreographer Dimitris Papaioannou draws on Greek classics and his visual arts background to examine life and death and search for the sacred

- June’s production just one of tantalising tales featuring Orpheus and Eurydice, Zeus, Hermes, Elektra and Apollo that continue to captivate global audiences

The Greek myths – full as they are with cruelty and death, mystery and perversion – have never shied away from mankind’s most disturbing imaginings. Indeed, these stories, told by the ancient Greeks dating from 1100BC revel in the unsettling.

Take Tantalus, for example. He killed his son, roasted him, and served him up to the gods at a dinner party.

The gods were so enraged that they made him stand, thirsty and ravenous, for eternity in a pool of water with a heavily laden fruit tree nearby. Each time he reached for the water it would recede and the tantalisingly close fruit was always just out of his grasp. This is the origin of the word “tantalising”.

Prometheus’ punishment was more violent: after stealing fire from the gods and giving it to man, he was bound to a rock, where each day an eagle would eat his liver, only for it to grow back overnight and be eaten again the next day.

In Greek tragedy, which was a big civic festival art form, the tales took the people to the darkest places you could ever imagine as a way of helping them to dream better as effective citizens of a democratic community

Bringing darkness into the light of shared storytelling was key to the function of these myths.

“Particularly in Greek tragedy, which was a big civic festival art form, the tales took the people to the darkest places you could ever imagine as a way of helping them to dream better as effective citizens of a democratic community,” Dr Nick Lowe, reader in classics at Royal Holloway, University of London.

“Part of the trick is to set the stories in the deep past of what we recognise as the Greek Bronze Age centuries before – a remote, heroic, but also primeval world touched by mystery and horror that are no longer a regular part of our world.”

The stories, set at a comforting distance from the audience, are entertaining as well as gruesome. They also have an inherent plasticity that has allowed them to be reshaped over the centuries to appeal to different listeners.

“By the time they were first told in writing [in the poems attributed to Homer, which were the ancient world’s Bible and Shakespeare in one], they'd already been told and retold, imagined and reimagined by centuries of professional singers, Lowe says.

Part of the trick of Greek tragedy is to set the stories in the deep past – a remote, heroic, but also primeval world touched by mystery and horror that are no longer a regular part of our world

“They continued to be retold in other forms and media; the invention of theatre in particular, two centuries after Homer, allowed them to be brought to living, breathing 3D action.”

As a testament to the stories’ resilience and accessibility, they continue to be performed live today – reimagined in various forms, from stage plays to ballet, opera and contemporary dance.

Glance sparks eternal regret

L’Orfeo, by Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi, is considered opera’s first masterpiece. Written in 1607, it is based on the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, one of the most famous Greek myths.

The story follows the fate of Orpheus and his bride Eurydice, who is bitten by a snake on their wedding day and dies. Orpheus’ beautiful lyre-playing convinces the rulers of the underworld to allow his wife to return to the land of the living for a while longer, on the condition that he leads her home without looking back.

Orpheus has almost returned to the light when he can no longer bear the silence behind him and looks back. Eurydice is trapped in the underworld forever. In the myth, the mourning Orpheus is then ripped apart by wild beasts, but Monteverdi gives the opera a happier ending.

The themes of the story still echo with audiences today.

“Ever since Virgil – to whom we mainly owe it; we don’t have whatever Greek sources he was using – it's been about the power and limits of art, its ultimate failure to attain the impossible and breach the boundaries of death,” Lowe says.

“It’s mixing the figure of the supreme artist into an old story type [which goes all the way back to Homer] of trying and failing to bring back lost love.”

The story is one of opera’s most popular myths. From Jacopo Peri’s Euridice in 1600 to Joseph Haydn’s last opera L’anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice in 1791, and Harrison Birtwistle’s The Mask of Orpheus, which premiered in 1986, to Philip Glass’ chamber opera Orphée of 1991, composers have been inspired by the story for hundreds of years.

Revenge sparks violent obsession

The one-act opera, Elektra, by German composer Richard Strauss caused a public outcry when first performed in 1909 at the Semper Opera House in Dresden. Critics raged about it being a “sexual aberration”, “blood mania” and “a terrible deformation of sexual perversity”.

If each age reinvents classical mythology in its own image, Strauss and his librettist, the Austrian writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal, held a mirror to their times and the image was not pretty.

In Greek myth, Elektra was the daughter of King Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra. She and her brother Orestes plot revenge against their mother and stepfather Aegisthus for the murder of their father.

In Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s version, Elektra is a compulsive neurotic with a relentless thirst for blood, who sacrifices her sexuality for her obsession. A vision of hatred and endless violence, Strauss’ Elektra became a prophecy of the terrible upheavals of the 20th century.

Figure of terrifying beauty and power

George Balanchine’s interpretation of the myth of Apollo is one of the landmark ballets of the 20th century. The world-famous choreographer collaborated with Russian-born composer Igor Stravinsky, who wrote the score between 1927 and 1928, to create a mainly classical ballet.

It was a turning point in Balanchine’s career, when he moved from the modernism of earlier works to re-embrace and reinterpret classical choreography. It also marked the start of a long and fruitful collaborative relationship with Stravinsky.

The ballet premiered at the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt (now Théâtre de la Ville) in Paris on June 12, 1928, with Stravinsky conducting. Scenery and costumes, largely in white, were by French artist André Bauchant, while Coco Chanel provided new costumes in 1929.

Apollo’s a god with a fascinating portfolio: the god of prophecy and inspiration, music and healing, but also a figure of terrifying male beauty and power

In the Balanchine-Stravinsky version, Apollo – the Greek god of music – is visited by three muses: Terpsichore, muse of dance and song; Polyhymnia, muse of mime; and Calliope, muse of poetry.

The ballet takes classical antiquity as its subject, though its plot places it in a contemporary situation, suggesting the ballet is concerned with the reinvention of tradition. Far lighter than many other Greek myths, Apollo here is more concerned with mystery and the power of creativity.

Apollo has always been a captivating figure of Greek myth, especially when it comes to exploring creativity and the arts.

“He’s a god with a particularly fascinating portfolio within the pantheon – he's the god of prophecy and inspiration, of music and healing, but he’s also a figure of terrifying male beauty and power,” Lowe says.

Balanchine’s ballet is performed regularly today by dance companies around the world.

A matter of life and death

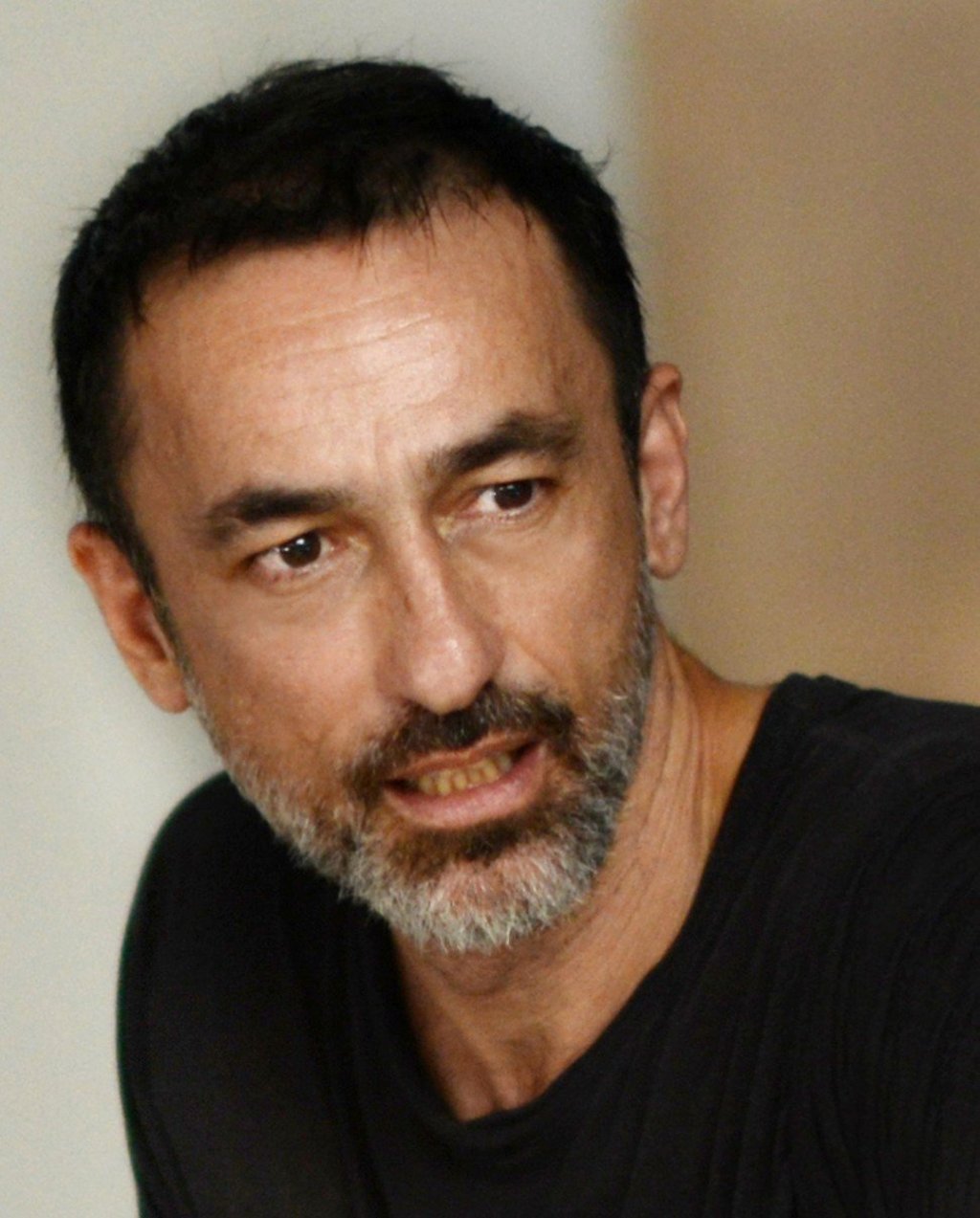

In the contemporary dance, The Great Tamer – which is being performed in Hong Kong from June 13 and 15 at the Hong Kong Cultural Centre – director and choreographer Dimitris Papaioannou draws on the Greek classics and his visual arts background to investigate life and death, existential exploration and the search for the sacred.

Trained at the Athens School of Fine Arts and a veteran of Greece’s theatrical avant-garde, Papaioannou is inspired particularly by the words of Homer.

In one scene of The Great Tamer, a tunic-clad female performer stands watching silently as hundreds of golden arrows shot into tiles make the stage shimmer like a field of wheat. Is it Persephone, the personification of the harvest, who was abducted by Hades when she was picking flowers?

In Homer’s epic, Hades takes Persephone to the underworld with him to be his wife, but her mother, Demeter, begs Zeus for her daughter back. Hermes is sent to rescue Persephone, but Hades tricks Persephone into eating pomegranate seeds, which, because she has tasted food in the underworld, means she must return each year – the time of winter.

In this production, the audience is also taken on a surreal visual journey, with an inclined stage built with removable charcoal grey plates that allow trap doors to open and shut at will. Performers disappear at random, as if they had been damned to the bowels of the Earth.

In one moment, the stage looks like a desolate wheat field, in another, a crushed skeleton or seemingly torn limbs emerge. The gravitational field in this world is unpredictable, as performers glide, walk on hands or even levitate.

Papaioannou also refers to the works of old masters – from El Greco to Rembrandt, Botticelli, Raphael and Magritte – building macabre still lifes, dreamlike images and nightmarish creations from 10 performers, his magical stagecraft, and a floor that shifts and reshapes.