Tales from old Zheltuga: the rise and equally abrupt fall of the lawless 19th century gold rush republic on the Russia-China frontier

- The town in the tundra on a tributary of the Amur River ballooned when gold fever hit, bringing drunkenness, opium abuse, violence and prostitution

- Declaring itself a republic was too much for the Chinese authorities who ordered it evacuated and, when defied, sent in troops to wipe it off the map

Today it’s hard to imagine such a place existed, but once, on the Sino-Siberian border, there was a kind of Wild West town, similar to those seen in California and Australia. At times of tension between Russia and China, that stretch has been contentious, but for a while in the 1880s, a raft of fortune-seekers descended, searching for gold, from the encampment on the banks of a tributary of a tributary of the mighty Amur river, called Zheltuga. At least 10,000 came within a few months, around 6,000 Chinese and 3,000 assorted others, mostly Russians. By 1885, The London Times would note the presence of “Americans, Australians and those come from the diamond fields’ (South Africa)”.

It was a harsh existence, there was no shortage of crime, vice or violence, but Zheltuga governed itself and answered to no one. A boomtown it was not, however, and soon enough it was gone, all traces lost in the tundra, as fast as the prospectors’ dreams of riches had fled.

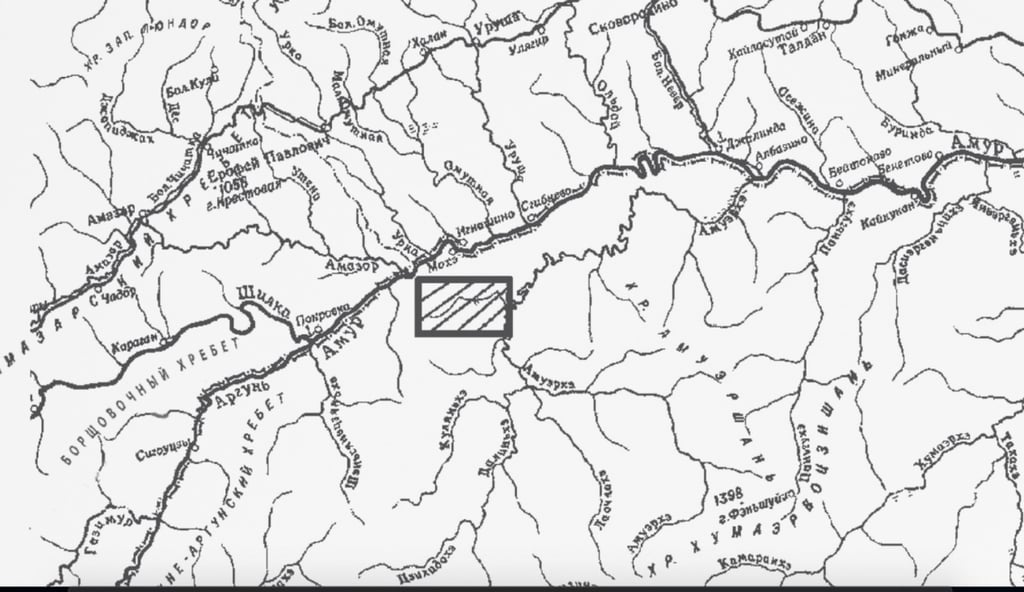

The Amur River, or Heilongjiang to the Chinese, forms a natural 2,735km border between Russia’s Far Eastern territories and China’s northeast, a land freezing in winter, boiling in summer. Traditionally, it has been somewhat depopulated on the Russian side while, in recent years, a number of vibrant Chinese cities have emerged. Among them are the northernmost designated tourism town of Mohe (“China’s Arctic Town”), the grasslands city of Hailar, and Heihe, facing across the Amur to Blagoveshchensk, the administrative centre of Russia’s Amur Oblast.

In the late 1890s, Russian engineer Nikolai Garin was sailing down the Amur, scouting possible railroad routes across Siberia. One evening he spied a settlement not marked on his map. Upon inquiry, he was told that in 1883 a man from the Orochen tribe indigenous to the Amur region was digging a grave for his recently deceased mother in a valley not far from Mohe. He unearthed a seam of gold along the banks of the Zhelta, a tributary of the Albazikha, which itself eventually flows into the Amur. As news of his find leaked, the settlement grew and by 1884 a sizeable community had been established.

Word of Zheltuga spread by way of the tsarist and Qing newspapers of the region, a trickle became a flood, and a full-on gold rush began. The hopeful Russian prospectors who illegally crossed the Sino-Russian border, as well as the northern Chinese dreamers who flocked even farther north, all called it Zheltuga Ignashinskaia Kaliforniia (due to its proximity to the Russian Cossack station of Ignashino). They hoped it might match the great riches of the California gold rush 30 or so years earlier, the stuff of every prospector’s dreams.

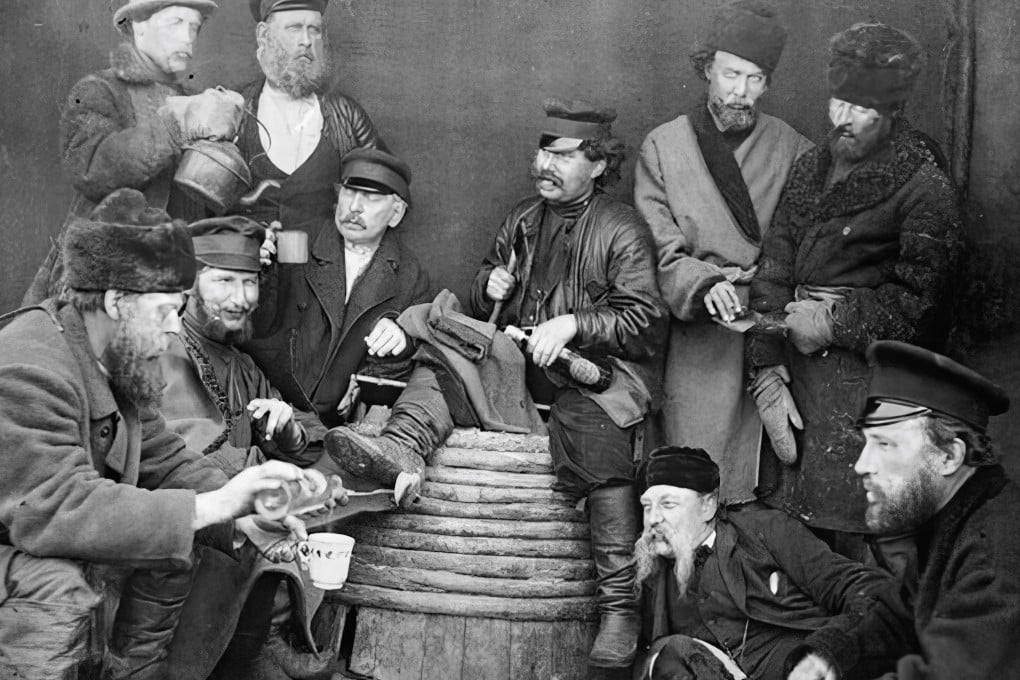

Professor Mark Gamsa of Tel Aviv University, a historian of Russia and China, and the foremost authority on the Zheltuga Republic, has written that “by the very nature of its activity, Zheltuga became a magnet for criminal elements”, and the new arrivals were indeed a motley crew, to say nothing of the Parisian journal La Revue Blanche reporting the presence of nearby honghuzi (“red beards”), Chinese bandits who would roam the Sino-Russian borderlands.

Drawn in were Russians, mostly from the region around Blagoveshchensk, as well as the settlements of Chita and Nerchinsk; indigenous Evenki tribesmen from the Sino-Russian borderlands; Chinese labourers looking to escape endemic poverty in Shandong province and fanning out across Manchuria looking for work with nothing but muscle; Manchu tribesmen from further east up the Amur seeking to break free of their poverty-ridden lives as nomads. There were also those who had wasted their time on other, failed, gold mines in Russia, who prayed Zheltuga would finally be their land of plenty. Less desirable were the escaped convicts from the tsarist penal colonies at Nerchinsk (which included the convict-mined Kara goldfields) and on Sakhalin island (known as Sakhalintsy), who also flocked to the ostensibly lawless Zheltuga.