Malcolm Gladwell on Talking to Strangers, trust issues and transparency

- In his latest book, the New York-based bestselling author and journalist explores how our natural inclination to believe each other allowed people such as Bernie Madoff and prolific paedophile Jerry Sandusky to get away with their crimes for so long

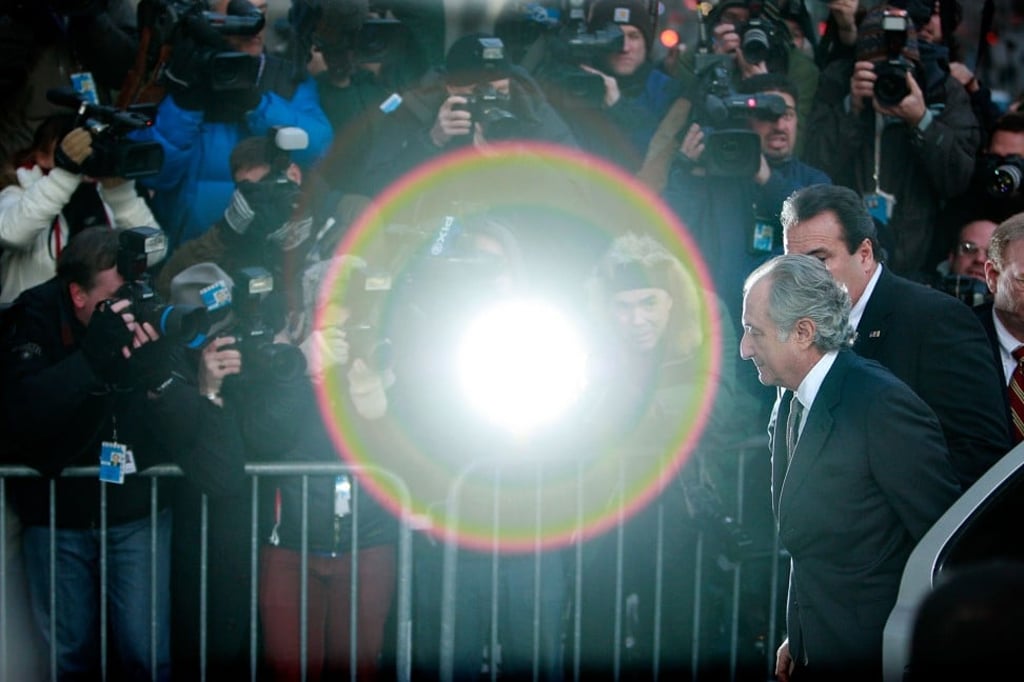

In the years before Wall Street financier Bernie Madoff was jailed for operating the largest Ponzi scheme in history, numerous individuals had suspicions about him. Renaissance Technologies, a New York-based hedge fund that found itself with a stake in one of his funds, thought something was amiss and concluded after an investigation that “none of it seems to add up”. But rather than sell its stake, it just halved it, an executive later telling investigators, “I never, as the manager, entertained the thought that it was truly fraudulent.”

Peter Lamore, an investigator at the United States Securities and Exchange Commission, tackled Madoff in person about why, in defiance of all logic, his returns did not go up and down as stock markets went up and down.Madoff replied that he had an infallible “gut feel” for when to get out just before a downturn. Lamore later recalled, “I thought his gut feel was, you know, strange, suspicious.” He took his concerns to his boss, who also had doubts but did not find Madoff’s claim “necessarily […] ridiculous”.

Why were so many evidently smart people incapable of accepting the truth? In his new book, Talking to Strangers: What We Should Know About the People We Don’t Know, Malcolm Gladwell, America’s most famous intellectual – whose postulations, such as that 10,000 hours of practice are required to achieve mastery in any field have changed the way we think, and whose observations, such as that you can boost your child’s chances in life by delaying their entrance into kindergarten, have altered behaviour – presents a hypothesis: humans have a default tendency to believe other humans.

It goes against what seems to be happening in politics and social networking, but Gladwell uses research from social scientists to illustrate that our natural operating assumption is that people are honest. It’s why, he argues, a spy went undetected at the highest levels of the Pentagon for years, why an American gymnastics coach who was convicted as a serial child molester continued to receive support from one of his victims even after 37,000 child porn images had been discovered on his computer. It’s also why British prime minister Neville Chamberlain believed Adolf Hitler when the German chancellor insisted he wasn’t going to invade Poland, and why we tend to believe cheating spouses when they deny they are having an affair.

It’s fascinating. The book contains various lessons (“The harder we work at getting strangers to reveal themselves, the more elusive they become”; “The right way to talk to strangers is with caution and humility”, etc). And like its predecessors – The Tipping Point (2000), Blink (2005), Outliers (2008), What the Dog Saw (2009) and David and Goliath (2013) – is packed with dazzling facts. Did you know that when the US Transport Security Administration conducts audits at airports, 95 per cent of the time guns and bombs go undetected? Or that banning handguns could save 10,000 lives a year, just from thwarted suicides?

Among the book’s cultural insights: Sylvia Plath’s death may have been a symptom of the fact that, before “town gas” was replaced by natural gas in British households, many homes had “readily available lethal means”, with suicide rates for women in England in the early 1960s being the highest on record. All of which makes for a self-conscious meeting at the Covent Garden Hotel, in London.