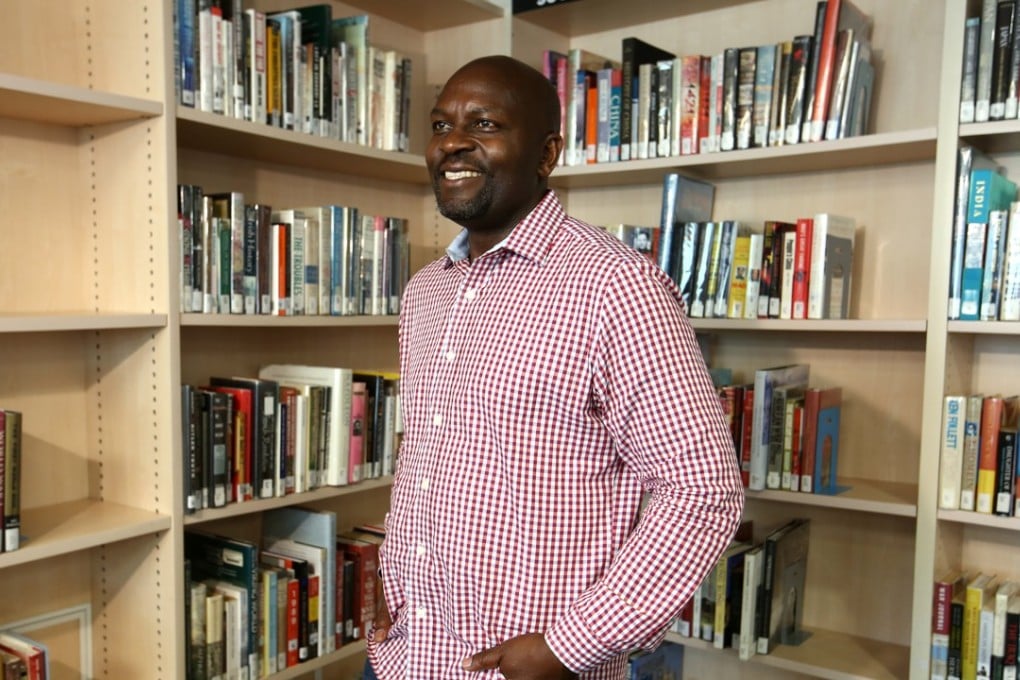

How schools bring hope to Aids orphans in Uganda, ‘the poorest of the poor’

Twesigye Jackson Kaguri, the founder and CEO of Nyaka Aids Orphans Project, talks about losing his brother and sister, founding schools in Uganda and the role of grandmothers throughout his personal and professional journey

A village in Uganda I was born in 1970 in a tiny village in Uganda called Nyakagyezi, or Nyaka for short. I am one of five children – the firstborn was a boy, the last-born was me and in between we had three sisters. My parents were – and still are – peasants. They grow food and raise goats. We lived in a small, grass-thatched house with one room for the five children and one for my parents with space in one corner for the goats.

Goats for grades My mum and dad had decided that all five of us were going to go to school. Given their economic situation, this was a huge undertaking. School started at the age of five. At 4½ years old, I observed my sisters going to school. They would wake up, put on their uniforms and be gone all day.

I decided to start following them. They caught me a few times, but when I did eventually get to the school, which took me forever as it was 7½ miles from our house, I snuck in. As I was trying to climb to look into the classroom, I turned to find my dad standing behind me. That day he took me home and told me I was too young to go to school, and that if I were to go now I would fail my exams. But he was tired of chasing me, and said, “I’m going to send you to school tomorrow, but if you fail one class, you will never go back. Do you want to go?” Of course I did, so the next day he sold a goat and sent me to school. And I have never failed an exam in my life.

Brighter for boys I loved school. And I started looking at a brighter future. I understood immediately that if you do well, you keep going. Your parents send you so you can have a better life. But they also send you so you can come back and take care of them. Education is an investment in human capital. My sisters finished high school but after that, my dad told them to get married so their brother could continue going to school. When I finished school, I sent my sisters back to complete their education. Now, of my two sisters who are still alive, one is a teacher and the other is a businesswoman.

Rights and wrongs The government would pay for us to go to university if we finished high school and performed within the top 1 per cent of the nation, which I did. I wanted to be a lawyer. I wanted to sue my father – he gave us school fees but he also beat my mother.

I missed the points required to get into law school and ended up doing social studies at Makerere University (in the Ugandan capital of Kampala) in 1990. One day our professor was reading the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which says that every human has a right to health and education. I raised my hand and said, “Do you mean every human being in the world?” He said yes. And I said, “There’s a problem here: either people in my village are not human or the people who wrote this document are wrong.”