Are Chinatowns obsolete, asks Madeleine Thien, Canadian novelist who grew up in one

Forged by anti-Chinese attitudes and laws, these tightly knit communities brought both business opportunities and solace for immigrants

When we were young, my sister and I were members of Vancouver Chinatown’s traditional dance troupe. Dressed as peacocks and tea pickers, complete with swirling ribbons or painted fans, we were joyful and colourful ornaments in a neighbourhood that, in the early 1980s, was impoverished but proudly vibrant.

My family had arrived in Canada, via Hong Kong and Malaysia, in 1974. My parents worked multiple jobs and sent us to school on the edges of Chinatown. Daily Chinese classes failed to dent our English selves – we refused to speak Cantonese, except to order food, when, briefly and miraculously, we became fluent. For my parents, the Chinatown enclave was both a magical kingdom and a refuge, perhaps the only place in which they could forget their worries for a while.

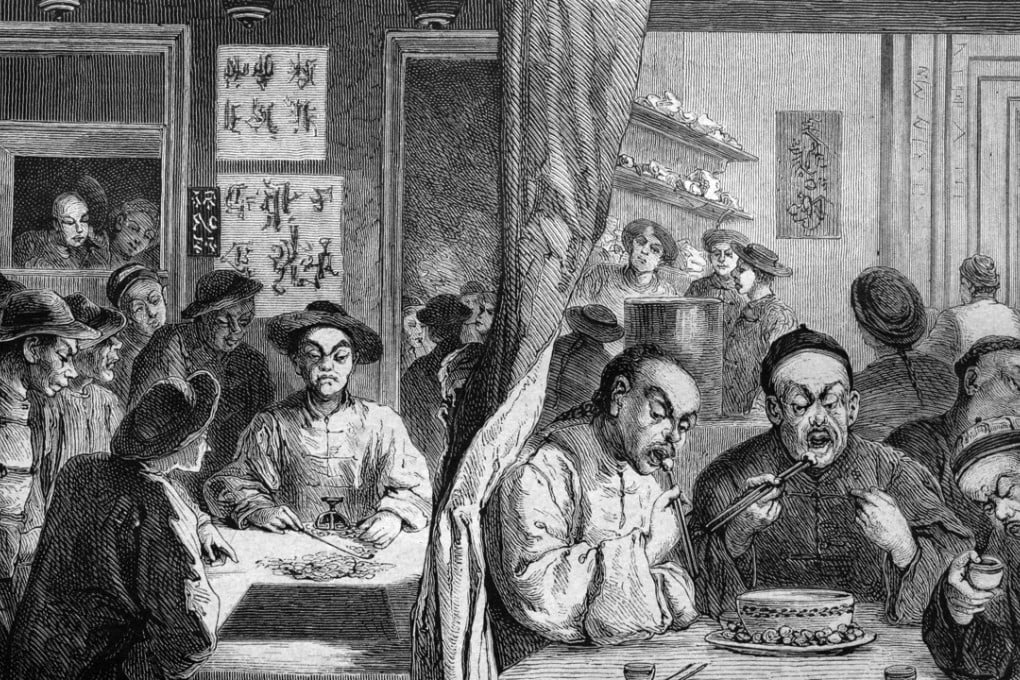

An editorial in British Columbia Magazine in 1911 warned of the “frightful and irrational fecundity of the race”, and a cheap labour force that, in the words of the local daily newspaper, World, consisted of “a degraded humanity”. The city and federal government passed a battery of discriminatory measures against the Chinese, including a C$500 head tax (the government collected C$33 million in these arrival taxes, the equivalent of C$321 million, or US$257 million today), curfews, levies, disenfranchisement and an immigration exclusion law.

Targeted by violence, forced out of mainstream trade by anti-Chinese by-laws and reviled as a public menace – “I consider their habits are as filthy as their morals,” the provincial secretary told a Royal Commission in 1885 – the community had only itself to rely on.

Across North America, Chinatowns developed a parallel civic society, providing schools, benevolent associations, libraries and a complex social organisation. Gradually, a self-protective architecture evolved: colourful facades that would satisfy an outsider’s desire for a contained, exotic experience – and an inner world that could meet the everyday needs of Chinese workers segregated into an increasingly crowded space.