Witnesses to horror: the Allied civilians in wartime Hong Kong who watched, helpless, as Chinese starved at hands of Japanese

Fear, isolation and constant danger were the lot of Allied civilians initially spared internment in second world war Hong Kong, but that was nothing compared to the atrocities Japanese perpetrated on city’s Chinese population

Soon after dawn on Sunday, May 2, 1943, a contingent of Japanese marines made a dramatic entrance into the compound surrounding St Paul’s Hospital, in Causeway Bay. Behind them was a team of gendarmes from the Kempeitai – the dreaded “Japanese Gestapo”.

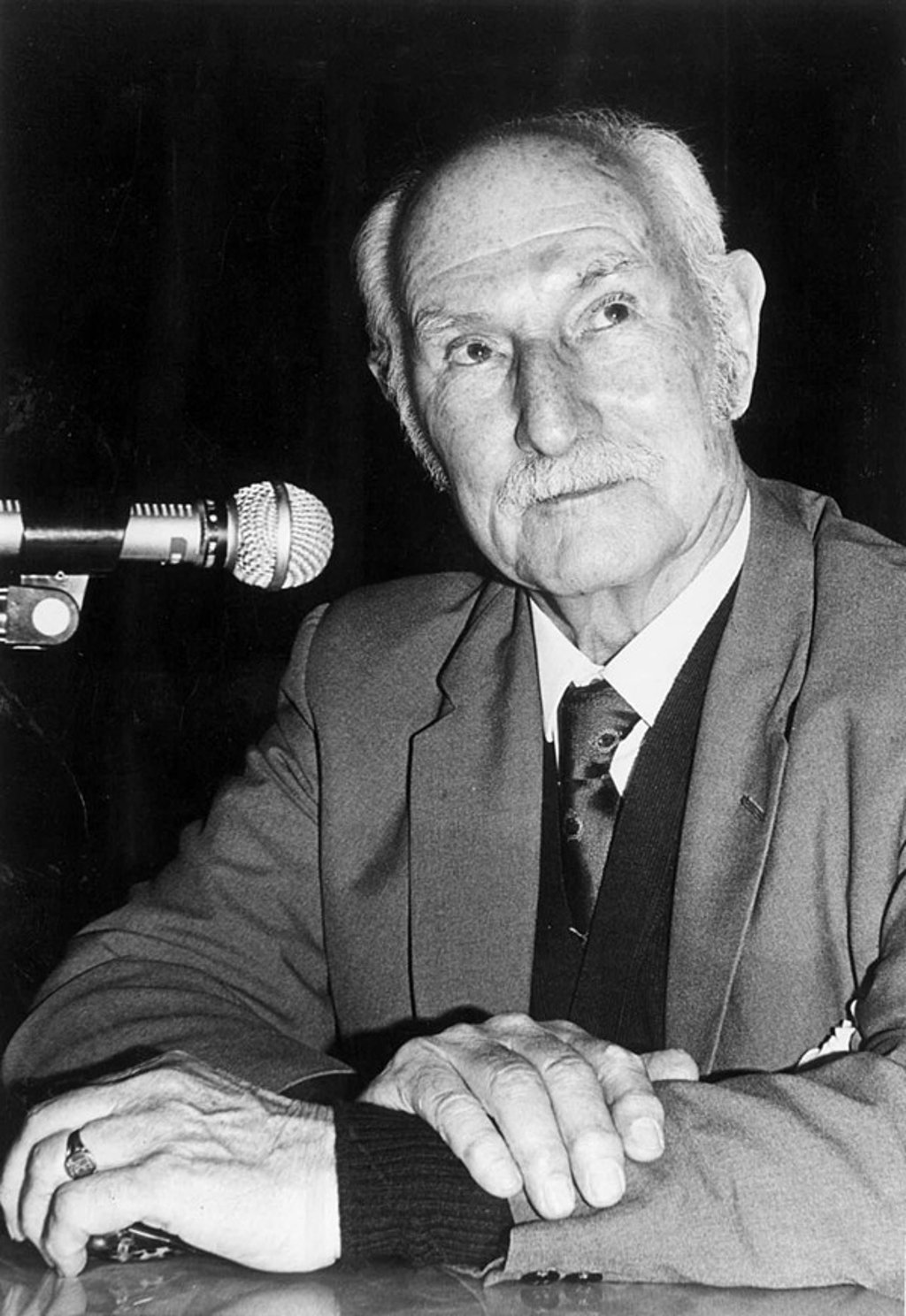

They had come to arrest Dr Percy Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke, Hong Kong’s former director of medical services, who had been allowed to remain outside the Stanley civilian internment camp to act as a public health adviser to the Japanese. The Kempeitai believed that Selwyn-Clarke’s medical work was a front for his role as leader of a British espionage ring sending information into Free China.

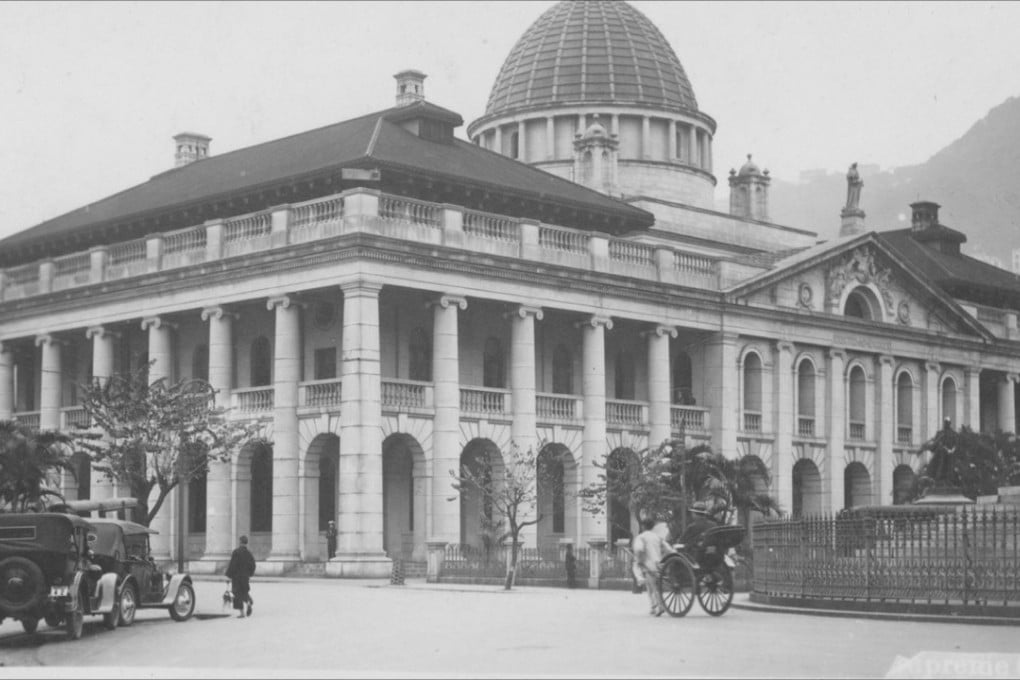

The iron gate leading into the compound was locked behind them as the Japanese headed for the hospital. They were looking for the billet in which the doctor, his wife, Hilda, and their young daughter were living, and their noisy search must have added to the general terror. When the Kempeitai found the room they were looking for, they told Selwyn-Clarke to get dressed. He was to go with them to their headquarters, in Central, in what had once been the Supreme Court Building.

“Not even the strongest can be sure that the methods of investigation employed by people of this kind will not break him,” he wrote in his autobiography, Footprints: The Memoirs of Sir Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke (1975).

His assistant, former Medical Department accountant Frank Angus, and the other doctors were forced to sit in the corridor while the Kempeitai searched their rooms. They were looking for radio sets, large sums of money – anything that would prove the hospital was the centre of a British spy ring. It didn’t take long to find the banknotes that Selwyn-Clarke had secreted around his room, and there was a radio hidden nearby, possession of which meant torture and possible death. Would the searchers find that, too?