Humble Hong Kong copper bolt that’s a key to naval history

What links a bolt hammered into a granite block in 1866 to the fight against the slave trade, an eminent naval architect and height measurements for every high point and high-rise in Hong Kong?

Eminent Scotsman John Buchan (1875-1940) was an author of what, among other more sober works, he called “shockers”, such as The Thirty-Nine Steps. He described them as fictions “where the incidents defy the probabilities, and march just inside the borders of the possible”.

Indeed, as Dr Tom Greenslade, one of Buchan’s characters in The Three Hostages, put it, “Take three things a long way apart [...] invent a connection [and] weave all three into [a] yarn. The reader, who knows nothing about the three at the start, is puzzled [...] intrigued [and] finally satisfied [...] for he doesn’t realise that the author fixed upon the solution first, and then invented a problem to suit it.”

The first piece in the puzzle is the story of the revolution that transformed ship design and building during the 19th century. Ships that had long depended on naturally occurring materials such as wood and canvas, and the energy of wind and muscle, became the steam-powered, screw-propelled, iron and, later, steel vessels on which the prosperity of ports such as Hong Kong was built. Suck-it-and-see design methods and the experienced eye of the traditional craftsman were replaced by the mathematically modelled, tank-tested designs of technically trained professional naval architects.

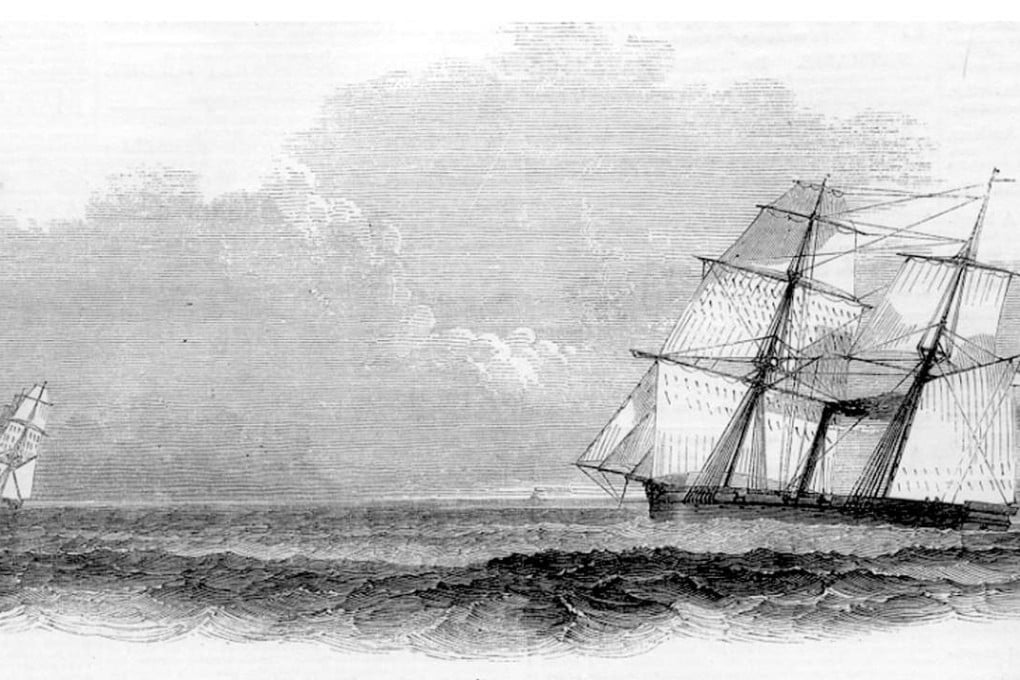

Anti-slavery patrols by ships of the British Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron, also known as the Preventative Squadron, were conducted between 1818 and 1870. Based out of Freetown, in Sierra Leone, the newly created future home for liberated slaves, the squadron always struggled. It had too few ships, the constraints of maritime law to contend with and too much ocean to cover. Even so, by the time it ceased to exist, 1,600 slave ships had been captured, 150,000 slaves freed and the trade in slaves effectively ended.