Art House: Giant shows the Hollywood studio system at its best

Not unlike James Dean himself, Giant (1956) is simultaneously subversive and thoroughly Hollywood. The sprawling 201-minute saga of Texas cattle and oil represents American-style filmmaking at its most epic — with the cinematography, panoramic vistas, and lavish sets being evidence of just what the studio system could achieve.

Giant's marquee is also stellar. The chief reason for the movie's continued fame is its integral part in the Dean legend as the last of his three starring roles, released more than a year after his death at the age of 24. Back in the day, his Academy Award-nominated portrayal was surpassed in celebrity wattage by those of Rock Hudson (also nominated) and Elizabeth Taylor.

Further corroborating the film's mainstream appeal is its huge budget and even larger box office returns, along with the industry approval indicated by 10 Oscar nominations, with a win for director George Stevens.

The surprise on revisiting Giant, then, is that this rollicking saga of big ranches and bigger gushers is much more than a typical Hollywood mega hit. This is chiefly due to Stevens' eagerness to retain the important elements of Edna Ferber's 1952 novel upon which the film is based and subtly incorporate its unorthodox undercurrents of dealing with social inequalities, be they based on race, sex, or social class.

Spanning the 1920s to the '50s, the narrative's personal and economic threads deftly intertwine as the discovery of "black gold" alters the fate of Giant's protagonists. The tale starts out conventionally enough, albeit with the romance between rancher Jordan "Bick" Benedict Jnr (Hudson) and East Coast socialite Leslie Lynnton (Taylor) saved from insipidness by the script's abundance of quirky individuality.

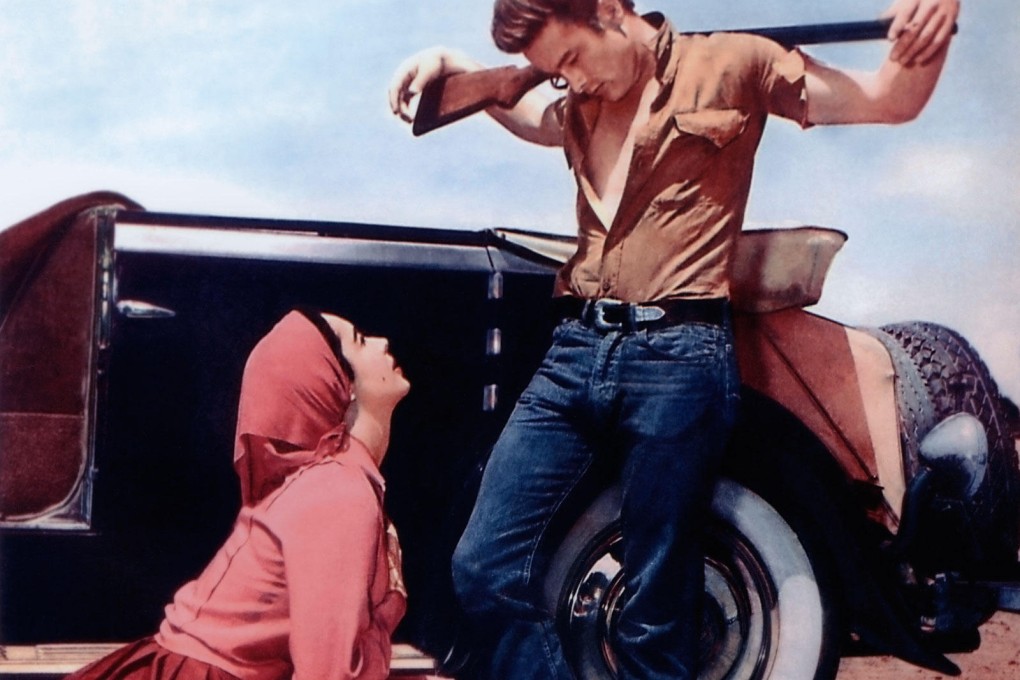

None is more individual than Jett Rink (Dean), a hired hand with grandiose dreams.