Tiny brine shrimp may help power ocean currents, US study shows

US study of humble brine ship suggests their movement affects mixing of ocean waters

Could the humble brine shrimp, a few millimetres in length, be partly responsible for the large-scale motion of the ocean?

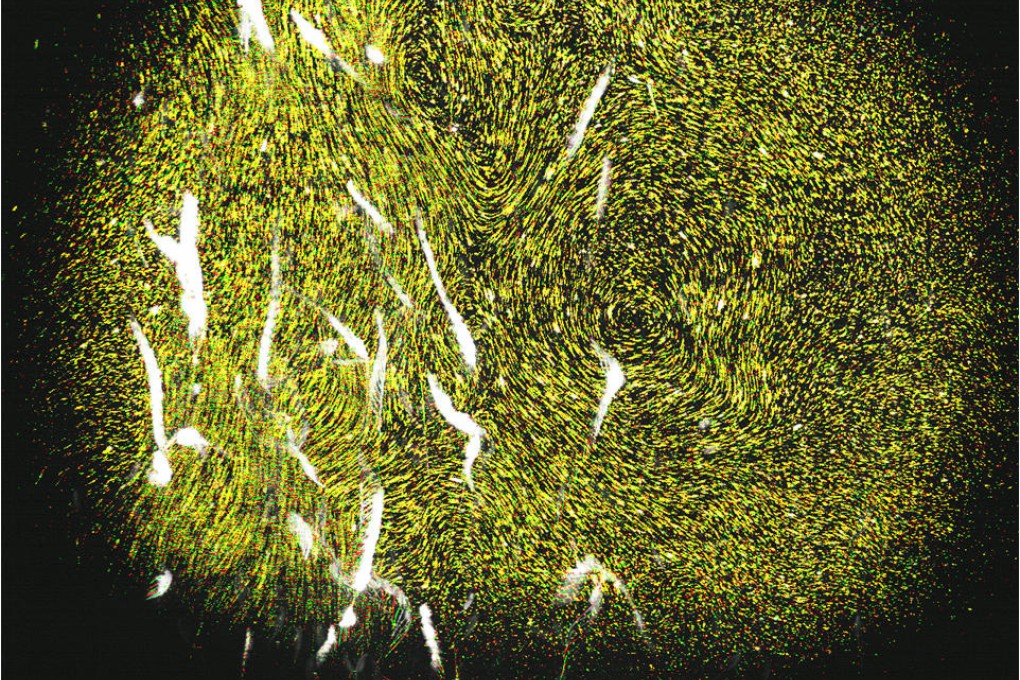

That's the finding by a pair of California Institute of Technology researchers, who used lasers to herd brine shrimp around a tank and track their effect on the water's movement. The results, published in the journal Physics of Fluids, show that ocean currents may be a function not only of large-scale physical phenomena like wind and tides, but also of living things.

Study co-author John Dabiri, a Caltech fluid dynamicist, latched on to the idea a few years ago while studying how jellyfish move. He noticed something strange: As the jellyfish swam, they appeared to be carrying a lot of water with them.

Dabiri wondered if the same was true of smaller animals that fill the world's oceans, including krill and copapods. He decided to study brine shrimp.

The tiny creatures are sensitive to light; they rise up during the night to feed on phytoplankton and sink back into the darker depths during the day.

Dabiri and graduate student Monica Wilhelmus wondered if these dramatic vertical migrations - in some cases, hundreds of metres - could be affecting the mixing of the water. But it's hard to track brine shrimp movements in their natural environment because, unlike the population of jellyfish studied earlier, it's hard to figure out where the tiny animals will be at any given time.