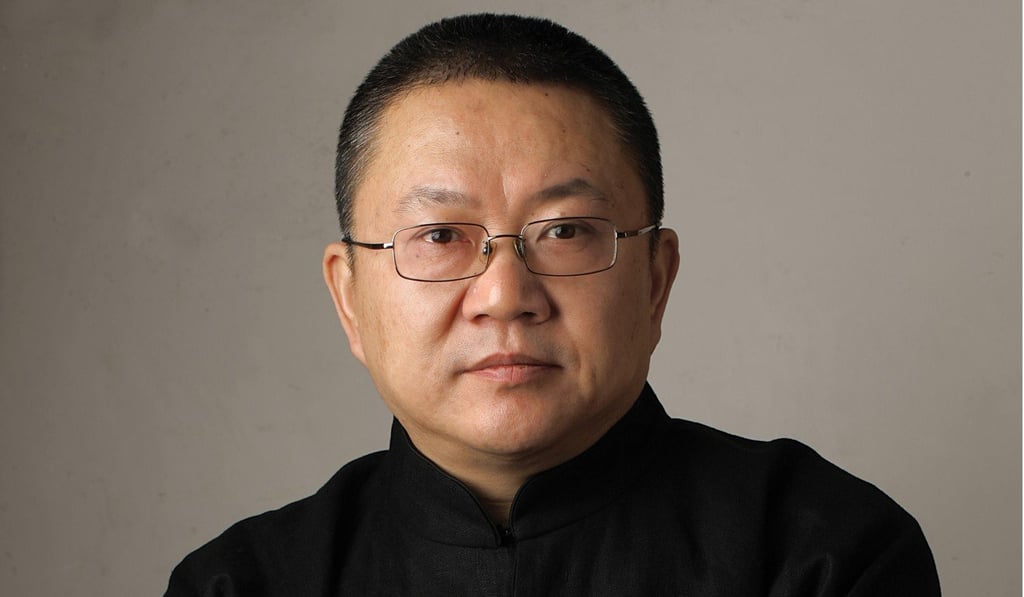

Pritzker Prize-winning Chinese architect Wang Shu battles to save China’s traditional rural building style amid rampant urbanisation

Wang Shu and his wife, Lu Wenyu, of China’s Amateur Architecture Studio want to protect Chinese culture and history by returning to artisanal building techniques and the use of materials such as natural stone, wood and bamboo

Wang Shu’s rejection of what he calls “professional, soulless architecture” has almost become a war cry. That kind of architecture, he believes, is ruining China.

“We are the largest construction site in the world, but the majority of materials used are concrete and steel,” he says. “There is almost no place for handmade, traditional and natural materials. But we are committed to turning that around. We want to bring back manual construction into modernisation.”

Wang’s rebuke of rampant modernisation, and the self-described “contemporary traditional” style, has gained his practice an international audience. It has struck a chord with the French in particular, which is why a major retrospective of his and his wife Lu Wenyu’s work is currently on show in Bordeaux.

Even the name of the architecture firm they founded in 1997 draws from their rebel-with-a-cause ethos. “We called it Amateur Architecture Studio because, in China, we have a lot of professional architects, but almost no good architects,” Wang says, chuckling softly. “Secondly, our Chinese tradition lies not in professional architects but the history of craftsmanship, which is quite different.” That’s why he prefers the title “artisan” to “architect”.

Wang also calls for the safeguarding of China’s threatened countryside against what he describes as the sweeping destruction of history and culture in the rush towards urbanisation. In 2012, he even became the first Chinese citizen to receive the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s most prestigious award, for his standpoint on the issue and for his commitment to reviving traditional craftsmanship. The jury cited his ability to transcend the usual past-versus-future, traditional-versus-modern divide in producing architecture that was “timeless, deeply rooted in its context and yet universal”.