The future of gene editing: ending disease or creating super-soldiers or a master race? Why rules are needed

- Chinese scientist He Jiankui’s intentions in creating world’s first genetically modified human babies were ostensibly good, but the technology has clear risks

- Scientists and a biohacker think it inevitable people will seek to use it for self-enhancement, making global regulation of its use vitally important

Within this century, human beings will be capable of changing their genes to modify traits like intelligence, or even instincts like aggression, the renowned physicist Stephen Hawking predicted. Months after his death earlier this year, a scientist in China shocked the world by announcing he had created the world’s first genetically modified human babies – a step towards the future Hawking envisioned.

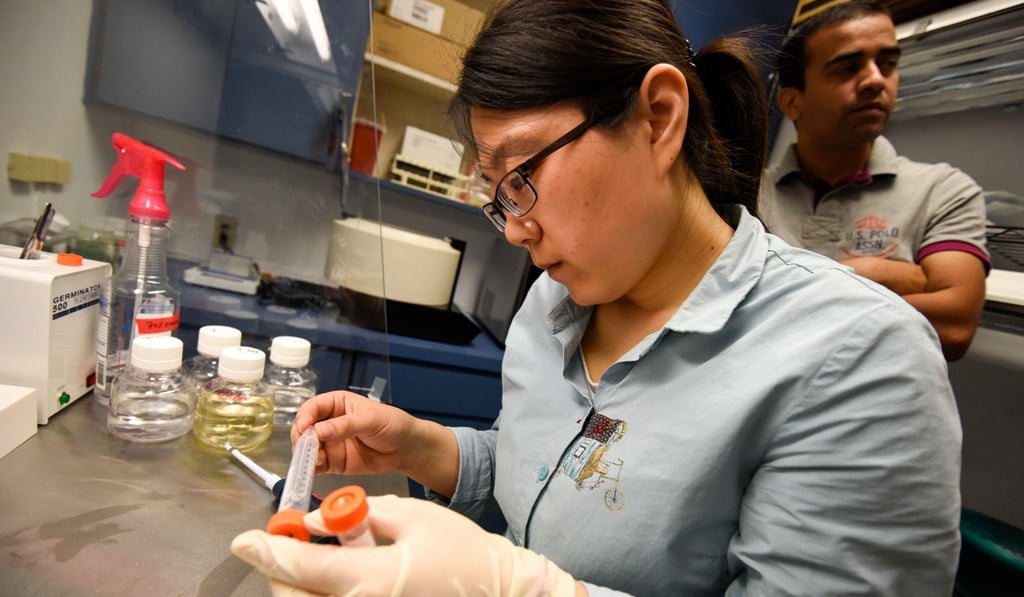

Chinese scientist He Jiankui’s use of gene editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 to engineer the birth of twin girls Lulu and Nana triggered a torrent of international criticism earlier this month.

Despite He’s ostensibly good intentions in making the girls resistant to HIV – their father is positive for the immunodeficiency virus – scientists gathered at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong condemned his intervention, which has not been independently verified, as irresponsible and a violation of international scientific norms.

For all the focus on He’s case, less coverage has been given to what impact the capability for real-time human genome editing will have around the world.

“Laws will probably be passed against genetic engineering with humans. But some won’t be able to resist the temptation to improve human characteristics, such as the size of memory, resistance to disease and the length of life,” wrote Hawking in a set of essays posthumously published in Brief Answers to the Big Questions.

Scientists have touted applications for genome editing as being beneficial for treating ailments and even curing diseases such as sickle cell anaemia and, potentially, cancer.