Book review: David Crystal’s history of punctuation is marked for success

Although the conventions of use might seem fixed, they continue to evolve, says Crystal in his fascinating study

For punctuation, 1890 was a traumatic year. At one stroke, about a quarter of a million apostrophes were wiped from the surface of the earth.

The decision by the US Board on Geographic Names to do away with “apostrophes suggesting possession or association” in names such as Pikes Peak and Harpers Ferry is one of the more dramatic examples of the changeable fortunes of the cluster of squiggles that pepper our written language.

David Crystal’s superb new book is packed full of illuminating examples of the political, social and technological forces that have driven the evolution of English punctuation. With crisp, tight prose punctuated with self-conscious precision, Crystal provides not only a historical guide but an indispensable reference manual that doesn’t so much lay down the law as provide a rational framework.

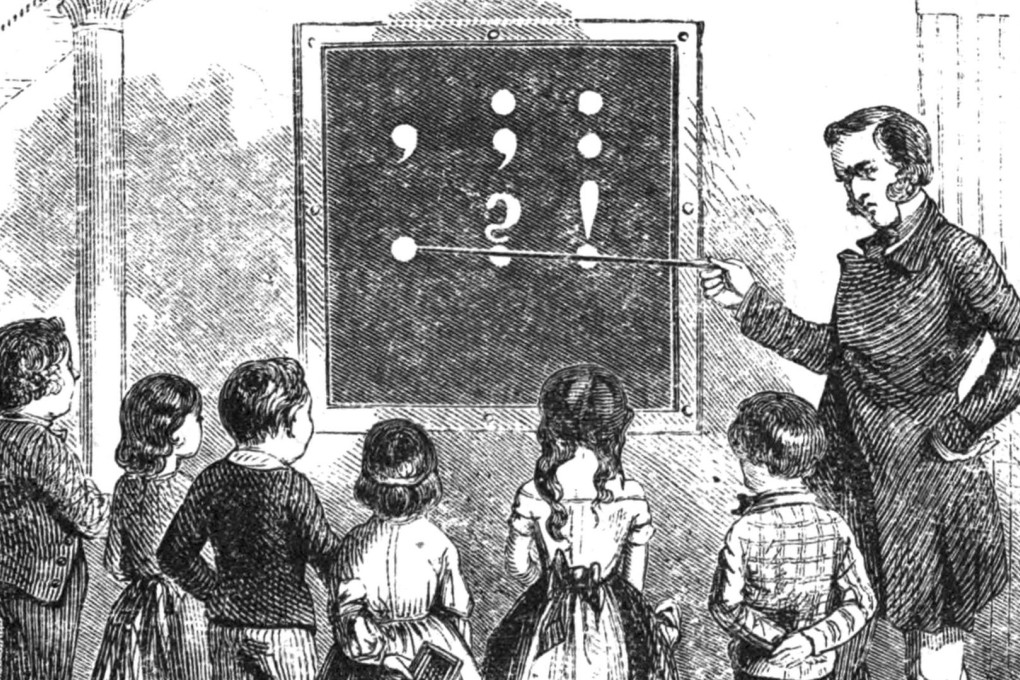

If you fret over the correct usage of the semicolon or comma, and would rather rewrite a phrase than invite the scorn of grammatical purists, then this book is for you. The rules of punctuation weren’t carved in tablets of stone. They developed over centuries into broad conventions, guided by warring factions. And they continue to evolve.

In the beginning, there was nothing. No capital letters to designate the beginning of sentences or names. No commas, question marks, apostrophes or full stops. Not even spaces between words. Writing was typically used for inscriptions or signposts and didn’t need them – just as today our street signs are typically unadorned. Longer script might be intended for skilled orators who, like Cicero, viewed punctuation as a crutch for unskilled and ill-prepared speakers.

As the written word spread, so did the need for some clues inside the text to guide less gifted readers. Spaces appeared between words. They might be separated by full stops or other marks, and not with any consistency or accepted practice. The copying of religious texts by monks as Christianity spread across Britain proved a major driver. Many early works were glossaries of Latin and English, which would have been unusable without spaces.