After the Orlando massacre, it’s important to remember why the gay disco matters – to everyone

As a barometer of a society’s inclusivity and as the crucible where modern dance music was forged, the gay nightclub has a huge significance, and not just for its patrons

The first time I went to a gay club, a stranger looked over his shoulder at me and said: “Aren’t you hot in that?” It was a Thursday night at the Number One, a small underground box tucked behind a police station in Manchester, with a ludicrous corner VIP area where you would occasionally see actors from the British soap opera Coronation Street.

It was run by a chirpy, resilient fellow named Bubbles. It was 1987 and I was 16, at sixth-form college a couple of miles down the road in Rusholme. That night, I begged, borrowed and eventually stole a chunky Ralph Lauren pullover from my big brother, not thinking that in a city that frequently entertained entire dance floors of men wearing cagoules, it would be any reason for concern. In front of the bar, I flinched, said “no”(a lie) and carried on taking in every detail of this new life.

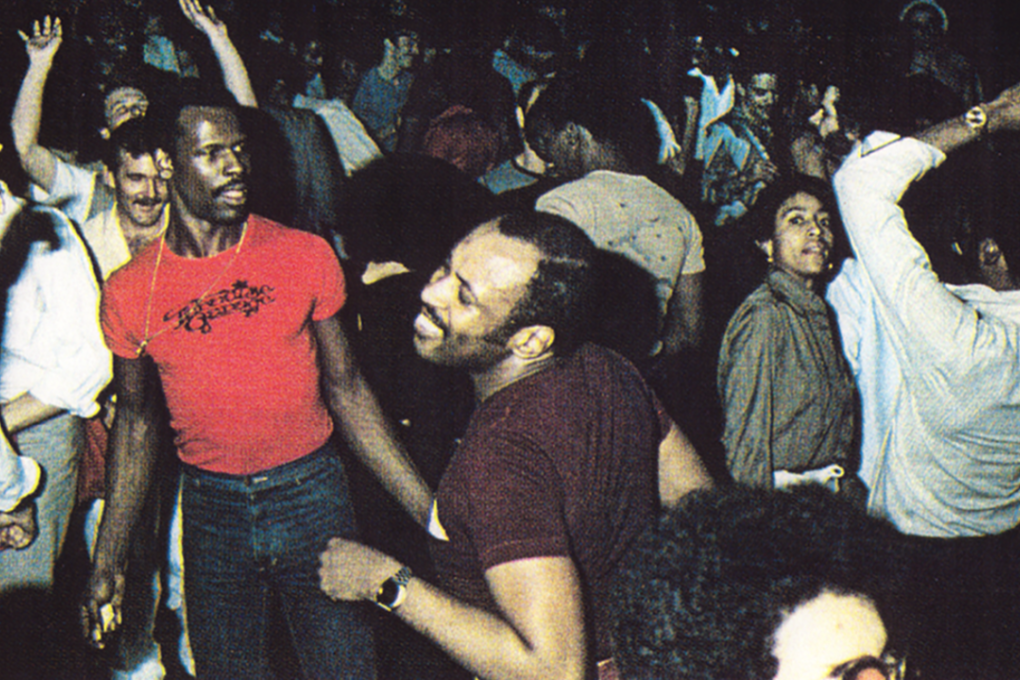

Collectively, we know the familiar mundanity of being in a workplace, on public transport, at school. We know first-hand the significant communion of attending a gig and the sanctity of being in church. When the severity of the bloodbath at Pulse in Orlando emerged, many could have imagined what clubbing on a Saturday night feels like, too. But not everyone is privy to the triumph of the neighbourhood gay disco. Maybe that’s why news bulletins about the dead and wounded, our spiritual allies, hit LGBT viewers as a personal affront, and provoked a militant anger.

The local gay disco is not supposed to be newsworthy. In the past 30 years, as the British LGBT cause has turned us from enemies to friends of the state, certain gay clubs have become enshrined in legend, turning the gay night-time experience into hallowed ground. UK gay clubs became unique mirrors to their individual political and sociological moment.

These are key moments in the fortification of the gay experience. They open us up to mainstream attention. We stop being something to be pitied, chastised, ostracised or othered and we turn into a party that everyone wants to go to. In the freedom and liberation floating through the air, there is something even to be a little envied.