Advertisement

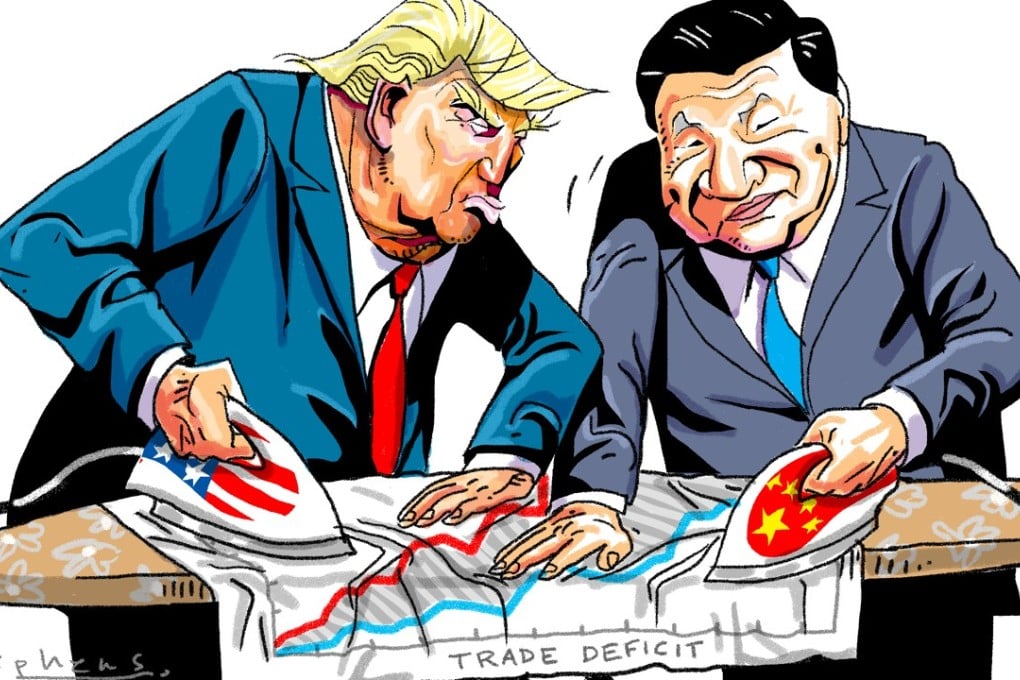

Opinion | The three issues Donald Trump and Xi Jinping need to iron out to end the trade war

- Yukon Huang says it will take more than one meeting to resolve US-China differences over complex issues, including the trade deficit, forced technology transfers and China’s technological ambitions

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Markets soared in early November when US President Donald Trump took the initiative to call Chinese President Xi Jinping and discuss ongoing trade tensions, but the optimism waned amid signals that attitudes have not shifted. As Washington waits to see what Beijing has to offer and Beijing waits to see what Washington wants, a prolonged stalemate is a more likely outcome.

The stalemate comes from a wide chasm in perceptions, as well as the absence of any institutional framework for resolving differences. Washington’s demands fall into three categories. Trump is fixated on the US’ huge trade deficit with China. The US business community is fixated with Chinese regulations that force foreign firms to transfer technology in exchange for access to the vast Chinese market. Washington’s geo-strategists are fixated on how China plans to become a technological power, thereby threatening the US’ global dominance. Put all three concerns together, and an impasse emerges.

The first demand would seem easy to meet: China should just buy more from the US. However, this idea is flawed and unworkable. Trade is a multilateral, not bilateral, issue. China cannot buy enough from the US to make a substantial dent in the bilateral trade deficit because the US does not produce enough of the high-end consumer goods that the rising Chinese middle class splurges on and Europe gladly provides, nor the raw materials that China imports from Latin America and Africa.

Advertisement

Even if China offers to buy more liquefied natural gas from the US, it will not prevent the deficit from rising in the near term. Then there is the hi-tech equipment Beijing wants, but which Washington will not sell on security grounds. This leaves China with only a beggar-thy-neighbour list of products to choose from: buy more soybeans but less from Brazil, more Boeing aircraft but fewer from Airbus. This does nothing to moderate China’s overall trade surplus but shifts the onus for adjustment onto other countries.

Advertisement

With regard to forced technology transfer, there is more room to manoeuvre. This should not be confused with intellectual property theft, for which there are available legal remedies. The issue is more technical. Foreign firms are required to form joint ventures with Chinese firms to invest in certain sectors – a common global practice – and asked to transfer technologies as part of the agreement.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x