Fortunately, we are not yet at a point at which war or acquiescence to North Korea’s nuclear status are inevitable, and

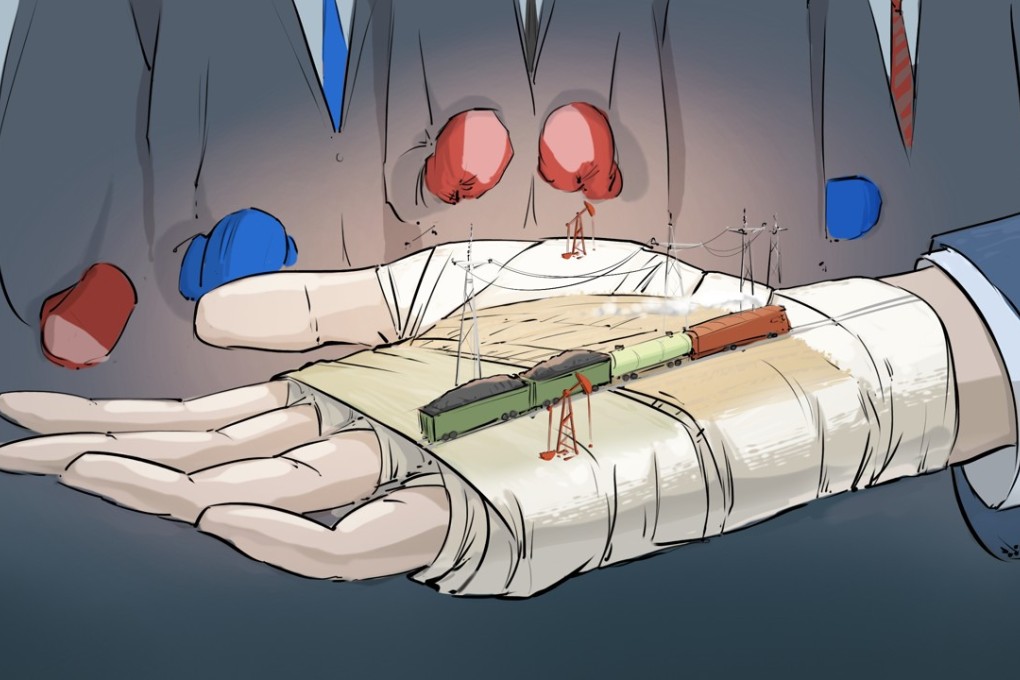

coercive diplomacy is still the best option. But to convince Pyongyang that it can never achieve regime security through nuclear weapons, the US, China, South Korea, Japan and Russia must collectively signal both clearer demands and credible assurances to bring the

Kim Jong-un regime to the negotiating table. And, in addition to addressing the immediate nuclear crisis, they must also find ways to integrate North Korea into the region so it does not become

another Iran – a state without nuclear arms but a destabilising actor nonetheless.

Watch: Celebrations in Pyongyang as North Korea tests latest missile

Just last week, the

UN Security Council passed another set of biting sanctions which will cut North Korea’s refined petroleum imports by 89 per cent come January and force North Korean workers abroad to return home within 24 months, among other measures. While these

measures will squeeze Pyongyang, it’s uncertain whether they will be quick and tough enough to change its strategic calculus.

Unfortunately, there’s not much left to threaten North Korea with, other than a complete embargo on its oil imports. The options that remain after that begin to veer into the category of military action, such as intercepting North Korean ships suspected of violating sanctions, or striking nuclear facilities and missile launch sites. Such steps have been avoided thus far out of fear of

provoking a response from North Korea and spiralling into a regional war. But, according to reports, the White House may now be seriously considering a

pre-emptive strike on North Korea, to give it a “bloody nose” and demonstrate that the

United States will not tolerate a nuclear North Korea.

A unilateral strike without any further clarification or coordination with other states would be counterproductive, to say the least. First, the move would immediately alienate the US from South Korea, China, and others who

insist military measures should not be used. Division among its neighbours is precisely what North Korea seeks and uses to its advantage. Second, pre-emptively “punching” North Korea “in the nose”, without making specific demands in advance, would undercut the purpose of coercive diplomacy, which is to induce a state to comply by threatening, but not actually using, force.

If, and when, the time comes when leaders believe threatening limited military strikes is the only means left to push the Kim regime to denuclearise and uphold the security of the region, everything possible must be done to maximise the odds that the threats will succeed, before force has to be employed.

Watch: Donald Trump speaks after North Korean missile launch

One basic step in this regard includes communicating explicit demands to Pyongyang, so that it understands what exactly it must do to avoid a strike. Simply stating it must give up its nuclear weapons, as the Trump administration has repeatedly expressed, is not precise enough. Does North Korea need to declare a moratorium on its missile and nuclear tests? Must it volunteer to turn over its weapons or open its borders to international nuclear inspectors? North Korean compliance is impossible if no one tells Kim Jong-un what satisfies our demands.