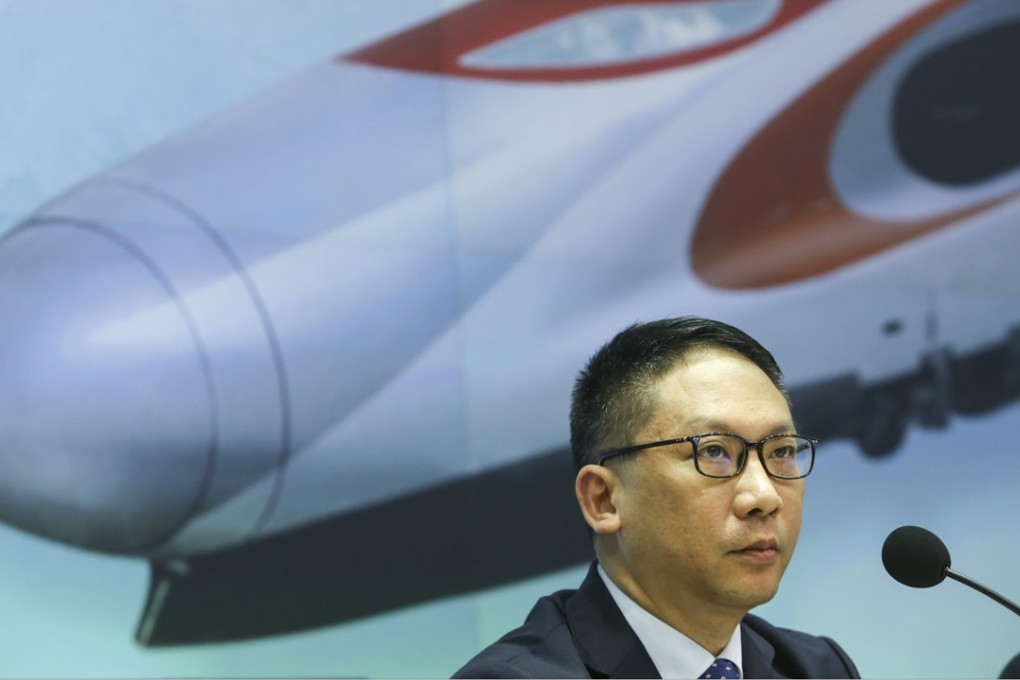

Why Hong Kong’s justice minister Rimsky Yuen is so sanguine about joint checkpoint for express rail link

Jason Y. Ng says the logic behind Rimsky Yuen’s support for immigration co-location at West Kowloon is unsound, but the justice minister’s confidence stems from knowing that Beijing always has the last word

The central question is a straightforward one: is the joint checkpoint proposal constitutional?

The answer can be found in Chapter II of the Basic Law, which governs the relationship between mainland China and Hong Kong. Articles 18 and 22 prohibit national laws from being applied in Hong Kong (with the exception of matters relating to defence and foreign affairs) and forbid Chinese authorities from interfering in the special administrative region’s affairs.

The pros and cons of different solutions to Hong Kong’s express rail checkpoint issue

In addition, Article 19 grants Hong Kong courts exclusive jurisdiction over cases that occur anywhere within the territory. That means any attempt to enforce Chinese law on Hong Kong soil – no matter the location or size of the area – is on the face of it in breach of at least three provisions of the Basic Law.