Is China’s belt and road ready to be the new face of globalisation?

Andreea Brînza says the initiative has plenty of ambition but still lacks a clear vision or some early project successes. And, importantly, China’s relatively weak soft power remains a drawback at this stage

In the past, the US led the wave of globalisation through its economic might, soft power and hyper-connectivity. But with the Trump administration now promoting protectionism, China has replaced the US as a standard-bearer for globalisation. This new face of globalisation has Asian features, too, thanks to Beijing’s new soft power strategy: the Belt and Road Initiative.

Formerly known as the “One Belt, One Road” strategy, it was interpreted by Western observers as an ellipse of roads, railways and pipelines which link China to Europe. The new name emphasises that the idea is much more than a single belt and a single maritime corridor; it’s more of a network of corridors and roads which connect all parts of Eurasia.

Still, a quick look at the map will make us understand that the Belt and Road Initiative is not only a connection by land and water, but specifically one that encapsulates all Chinese investments along the way. If it were only a road, railway or corridor, it would pass through conflict zones like Afghanistan. Therefore, we should see the belt and road more as a zone of investment, rather than a de facto road.

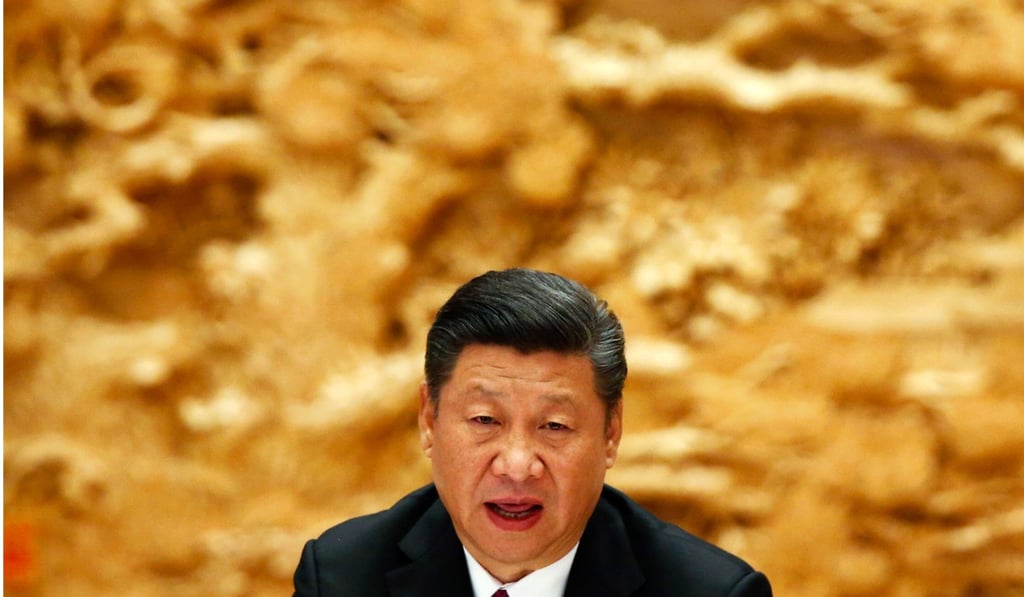

Moreover, the recent Chinese investments in Africa and Latin America, placed under the umbrella of the belt and road, support the idea of a worldwide strategy. Thus, the belt and road should be perceived as a Chinese strategy for the 21st century and as a new type of Chinese external policy. The belt and road may well be Xi Jinping’s (習近平) landmark strategy, similar to Hu Jintao’s (胡錦濤) “peaceful rise”.

Almost 30 state leaders put their support behind Xi Jinping’s new globalisation strategy