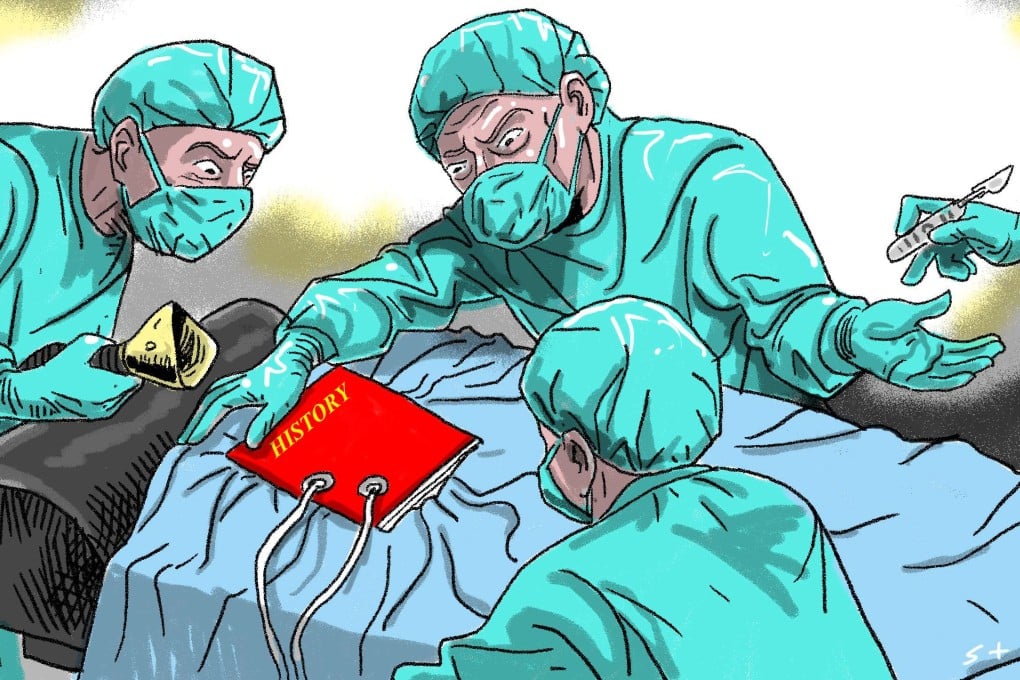

Chinese history can open the eyes of Hong Kong students, just don’t try to doctor it

Kerry Kennedy says if done right, the teaching of national history can help students grow into discerning individuals able to make their own judgments about their nation and national identity

One in three Hong Kong Form Five students faces ‘national identity crisis’: survey

Both sides obscure what should be a serious debate about what young people in Hong Kong should know and be able to do as a result of their school learning experiences.

The problem, when it comes to teaching Chinese history, is what history and whose history will be taught

It is not unusual, for example, for national history to be part of the learning experiences of young people as they prepare to be citizens. It is the case in the United States, Australia and the UK.

The teaching of national history is not inimical to democracy. If done well, it can be a strong support for democratic development and engagement. Yet there are always debates about the teaching of national history.

In the US, there are supporters of “black history”, “women’s history” and “Latina/Latino history” as part of the national story. Thus, the teaching of history is always contested.