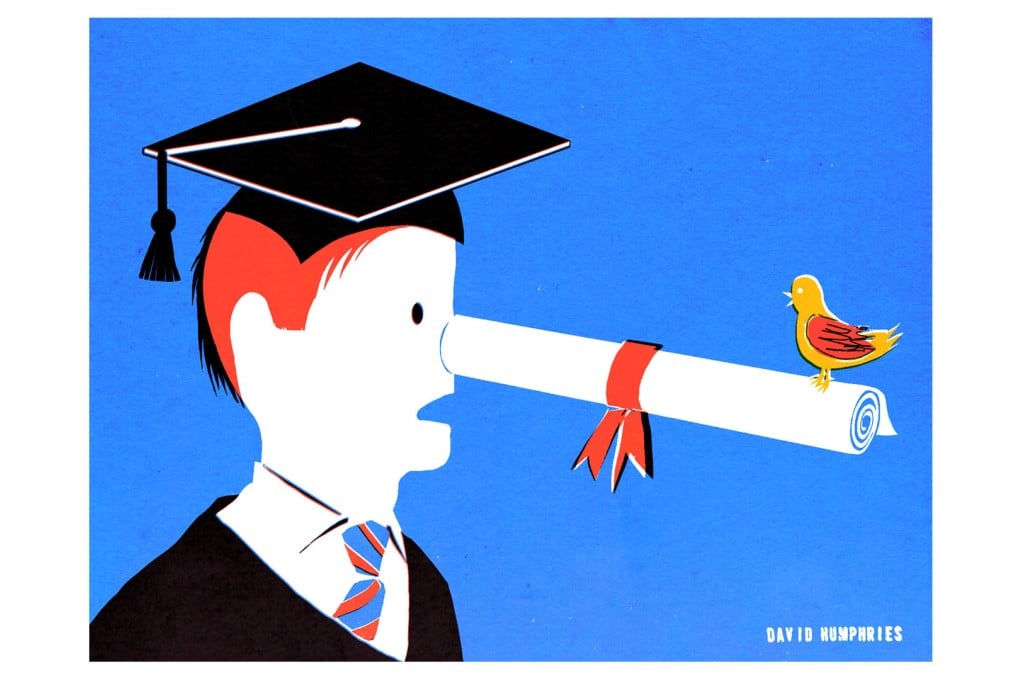

Universities should stop promising an education they cannot deliver

Neven Sesardic says if the wondrous benefits of a university education - beyond teaching basic skills for employment - sound too good to be true, it's because, in many cases, they are

Are universities selling people a bill of goods? Are they engaged in false advertising? If your answer is "Of course not!", this is for you. Students go to university mainly because it promises to teach them something that will give them the necessary qualifications for interesting and desirable jobs. For some jobs, this is really true. For example, one cannot become a doctor without studying medicine nor go into bridge construction without studying civil engineering.

But there are many areas of study (the "liberal arts" subjects such as cultural studies, history, philosophy, sociology) where most of what students learn does not immediately appear to be very useful for what they will typically do later in their careers.

Furthermore, even students of medicine and engineering have to take a lot of courses about topics that are neither connected with their narrow field nor readily associated with the acquisition of specific marketable skills. Among them are so-called "general education" or "core curriculum" courses, or "cluster courses" and "free electives". They usually take up a huge part of university studies.

When universities in Hong Kong recently switched from the three-year to the four-year system, out of the large number of the additional slots thereby created for new courses, all went to these "generic" (non-major) items.

Understandably, universities deny that this kind of knowledge is useless or irrelevant for employment. They claim that the study of liberal arts subjects and of general education courses also brings palpable practical benefits to students and increases their employability. But how? This is where things get murky.

Employers do have a preference for university graduates (including those with liberal arts degrees) over those who only finished high school. Doesn't this in itself demonstrate that there is important "added value" of higher education for purposes of employment?

Not necessarily. It is safe to say that those who enrol in university are on average already smarter than others to begin with. Perhaps it is mainly this pre-existing difference that gives them a critical advantage, rather than any knowledge or skills they acquire during their studies. On that assumption, the value of a university degree would consist largely in its signalling to employers the presence of those personal characteristics which are necessary qualities in a good employee but for which university could claim little credit.